Michel Foaleng

Université des Montagnes

Cameroon

Abstract – Global citizenship is only possible where individuals are able to engage locally in the identification and solution of their basic problems. The postcolonial education system of Cameroon, with its outdated teaching methods, produces poor scholars, who identify with the adult world through attitudes of hesitancy. We have not yet learned to be a citizen here. This is why citizenship education is currently recognised as a necessity. But its effectiveness presupposes that it is addressed not only to young people but to adults as well. One of the major challenges is to create an appropriate pedagogy for this purpose.

At the end of the Decade of Education for Sustainable Development (DESD), we would have liked to think that practices envisaged in this framework had been disseminated throughout the world and that in different countries citizens now have increased awareness of their responsibility regarding ways to sustainably improve their living conditions.

But today the debate on the agendas for post-2015 let us see that despite the diversity of contexts and irrespective of progress realised in certain areas on certain aspects, nowhere in the world have the goals of sustainable development (which obviously passes as appropriate education) been attained. In other words, the path remains long, not only to make adults capable of perceiving the terms of their vital problems, but also to be able to deal with them so that their solutions are carriers of universal values.

This contribution is based on a few commonplace observations of every day life in a secondary city in Cameroon. The idea is to try to reflect on the appropriate educational foundation to enable the people observed to effectively access a global citizenship, in this educational context where communicative methods (“knowledge transfer”) are predominant.

The use of the concept of “global citizenship” is becoming more and more common. This is a concept understood as variedly as it is multifaceted, with philosophical, ideological, legal and geopolitical connotations (Falk 1993, UNESCO 2013, Ghosh 2015). However, it is wrapped in a programmatic banner meant to improve understanding between individuals beyond the limits of territory. This is what seems to justify the international community being concerned, to the point that UNESCO was able to enact educational guidelines on the issue (UNESCO 2013). In effect, we are not automatically global citizens. We become; and we start from somewhere, a country, a community. One is a citizen, before becoming a citizen of the world.

A boy offers melon slices at a market in Cameroon © Michel Foaleng

Indeed, the notion of citizenship is an à priori appeal to both history and political geography that refers to an equality in rights and duties for a community sharing a certain space. The status of citizenship is usually formalised for each country, so that every individual can enjoy it with full knowledge of the reasons. However, beyond the formal dimension, citizenship is manifested through norms and values, attitudes and behaviours, relationships and expectations of individuals in a community. Citizenship is only attainable through action: no one can be automatically considered a citizen, you have to prove it by being active.

Sujay Ghosh (2015: 23), referring to Westheimer and Kahne (2004), differentiates between three types of citizens: the personally responsible citizen, who acts responsibly vis- à-vis the community (compliance with laws and regulations, etc.); the participatory citizen, who takes an active part in the affairs relating to the development of the community; the citizen concerned with justice, who questions the political and socio-economic structures of the sources of injustice and is engaged in order to change them. By its very name, a global citizen has to be in a relationship with others around the world to be global. Above all the global citizen must engage with others locally for respect of the law, for the best for all, for the reign of justice. Because if you have no sense of local citizenship you can never be a truly global citizen.

Such an understanding of the concept of citizenship based on action seems appropriate to clearly identify the issue, as well as the challenges of education for global citizenship. This is especially true in contexts where education in general suffers from a number of evils and the education of adults is almost nonexistent – as is currently the case in Cameroon.

An expression was born in Cameroon during the past decade and is currently one of the most common in the country: business citizen. This designation is given any business (through self-proclamation) that wants to develop its social “nonprofit” actions. These can be donation of some materials to a school or a hospital; gift of food to prisons or the army; sponsoring activities initiated by the government or municipalities; etc. Such “non-profit” actions are most often furtive acts of political or social positioning. They are without sustainability, being more relevant as a business communication or a political communication than a sustainable improvement of the living conditions of the people, the “beneficiaries” (cf. Metote 2012). So, is it not paradoxical that the expressions citizen action and citizens’ initiative are connected to the first (business citizen), even though the word citizen is hardly used in Cameroon? The country seems to be simply populated by masses who ignore acting together. We lack commitment to causes beyond the individual, causes to further the greater good.

Traditional dance performance in the Chiefdom of Bandjoun © Michel Foaleng

“Wait there then! It’s your problem. I said that if you want to see the doctor, come back tomorrow.” This is how a nurse responds to Ms. N. in order to resolve the concerns of the latter, who is worried about the survival of the three accident cases that she urgently brought to the district hospital in Famla/Bafoussam (a third-rank national hospital). Ms. N. has arrived from Foumbot, a village located 25km from Bafoussam, where she went to transport three of her husband’s employees, the victims of a serious traffic accident. These three young men were initially transported to the Foumbot District Hospital, located 5km from the accident. It was noon on a business day. All the staff were (supposedly) at their posts. Ms. N. decided to take them to Bafoussam because, after three hours, Oumarou, the driver of the truck in the accident, which unlike his two colleagues, transporter assistants, suffered from excruciating pain in the hip, had received no treatment, except for the x-ray that was performed. In this hospital too, she was told she had to wait for the doctor to read the x-ray, and no one knew when he would come. Finally, when Ms. N. arrives at the regional hospital, the largest in the region and a second-rank national hospital, she hopes that they will take diligent care of the accident victims. However, she has no illusions: she knows – because a few days earlier she had been there with another serious case – that in the “emergency room” where she goes, “nothing is urgent”. “When you get there, nobody insists on taking care of you. Too bad for you, if you arrive with bleeding patients; they die from loss of blood, without embarrassing anyone.”

In Bafoussam, the third largest city in Cameroon, with a population estimated officially at 500,000, we see how day after day the living conditions deteriorate. There are few roads where you can drive a vehicle for more than 10 metres without risking falling into a deep pothole. And when repairs are finally undertaken, the residents suffer even more: they are exposed day and night to the dust raised by traffic, dust which the contractors do not take any steps toward reducing, and which the victims take no action to oppose. Garbage is dumped anywhere, and Mr. K., a resident, has suffered from that in particular for many years. In front of his entrance is a dumping site that he has been fighting against for 10 years. He spoke about it with the head of his neighbourhood; tried to mobilise neighbours, so that together they could get rid of this garbage dump that infects the whole neighbourhood. He even sent a letter to the municipal hygiene service. Nothing has been done. The neighbours seem to have accustomed themselves very well to their environment. In fact, there is no other part of the city where housing is better: there are no paved roads or streets anywhere; women sell food for consumption on the dusty roadside or the streets in front of bars where the unbearable noise of music rubs shoulders every day with smells infested with urine and other human waste.

Some questions: Are the people here aware that in such conditions they destroy their own health daily? Do they know that they are primarily responsible for the way they live, and as such can take the initiative to improve it? Are they able to imagine living differently in a better ecological environment?

Also: You can be surprised at what may be described as a hospital emergency service. And we will reply that it is so in virtually all hospitals in the country, large or small. So why do nurses and doctors behave like this, manifesting contempt and a serious lack of professionalism vis-à-vis those who use the services and patients – since we are told that they received “excellent” quality training? Why are so many carers, encountered everywhere in these hospitals, resigned to their fate and are unable to take up any initiatives that could help them to create change – even though everyone suffers and complains?

No doubt the people of Bafoussam are – in their extremely precarious conditions – too accustomed to political slogans that promise action while inviting resignation; promises that make any declaration of good intent an utterance of falsehood regarding its performance: political speeches are generally media announcements made as if the announced action has been realised solely because it has been announced.

But there is also reason to believe that these people are victims of an education that deprives them of any sense of initiative. For, it must be said: school and education here prepare one more for consumption than production, for mimicry and not for critical thinking, for conformism and not for transformation. Thus here we are accustomed to waiting for others to act for us – if not simply: “may unto to us be done according to the will of God!”

Cameroon has made much quantitative progress in education since 2007 due to the pressure of the Fast Track initiative in the 2015 objectives for Education for All (EFA, today known as: GPE-Global Partnership for Education). And yet the Minister of Basic Education recognises that “it is clear that Cameroon will not achieve the 2015 target.” Worse, according to the current National Report on Education, “the results of studies on acquisitions of students in 2013 show that the quality of learning, which was pretty good for fifteen years, has progressively deteriorated: only a quarter of elementary students succeed in language and math tests” (Cameroon 2015: 50). In addition, “secondary education still faces the problem of relevance (subjects are in use dating from 40 to 50 years ago which no longer correspond to the current needs of society and the economy, education programmes which are deranged and outdated)” (ibid: 59).

In reality, the education system in Cameroon is a perfect model of frontal teaching, an expression of transmissive pedagogy. Teachers, even “progressives”, generally perceive their function uniquely in terms of “knowledge transfer”, even though they recite the precepts of active pedagogies, according to which the student should be “at the centre of learning” and that the teacher “is nothing other than his guide”, etc. The use of outdated teaching methods accommodates the teaching/learning conditions and doesn’t leave a lot of choices to the teacher: large classes, no equipment, no appropriate teaching materials, etc.

Education for citizenship is left to the NGOs, working without a framework national policy. Producing such a policy remains a challenge for the government (Cameroon 2015: 25). Adult education, when there is some, is mostly about literacy, while we officially recognise “the lack of a national policy for adult literacy, insufficient offers and essentially privately provided, as well as an absence of public funding” (Cameroon 2015: 42).

So, we are here in a society with schools that have 3 out of 4 students who would have difficulty reading; with predominantly illiterate adults who are abandoned to themselves in terms of education; in a society where the notion of citizenship has no meaning for the many and where resignation and resourcefulness reign as the main features of African postcolonial societies (cf. Foaleng 2002, Seukwa 2007).

How to proceed in such a society in order to hope that people can efficiently gain access (that is to say, in a transformative manner) to global citizenship?

Cameroonian efforts

Cameroon recognises the limitations of the current education system and is committed to improving it. Thus its post 2015 prospectus aims not only at the achievement of the six key EFA goals (World Education Forum 2000), but the Cameroon government has even recommended a seventh goal: education for citizenship (Cameroon 2015: 7). This seventh goal reflects the desire of Cameroon to prepare today for the citizenship of tomorrow, since citizenship education is required here at school. It is still unclear what the programme would be and especially the educational approaches.

Such education would however be in vain if at the same time adults, parents of the students, were not also put into citizenship school, so that they are not a barrier to learning for the young. This is why adult education seems to us here to be equally, if not more, urgent. But it could be even more difficult to think about than that for young people, since in this case one is talking about a concept which has been completely ignored. So, how to proceed?

The utility of community education

According to the Education and Development Foundation (Fondation Education et Développement 2010: 8), or UNESCO (2013: 3) citizenship education should have as its primary objective to make the learners, young or adult, able to live and work together, especially in respect of universally shared values. Such an education for adults could form part of lifelong education. But in a context like that of Bafoussam, where there is virtually no space for adult education, it would have to be invented.

Community-based education, for this purpose, seems to us to be an adequate approach. This is an educational approach in which members of a community acquire knowledge, know-how, self-knowledge and develop, through them, the skills and confidence required not just to eff ectively participate in the identification of problems in their environment, but also to the creation of solutions for them. Community education is individuals embracing their own destiny through individual and collective actions that transform them and positively change their environment. In order for community education to be effective, it must be based on educational programmes relevant to the community.

Everyday scene at a market in a small town in Cameroon, © Michel Foaleng

Such an approach also meets the criteria of fl exibility of learning spaces. Community education can easily use any space where adults meet, without requiring them to change their usual schedules.

Structured spaces for adults certainly do not exist in Bafoussam, where we think of the fundamental problems of society in terms of sustainable solutions. But you rarely meet someone in the area who is not a member of some type of association. In addition, many take part in weekly religious services in various churches to which they belong; funeral services which are usually held on weekends always mobilise hundreds or even thousands of adults.

Transforming these various spaces into places for community education for adults will mean developing and implementing participatory programmes that serve as supports for change, of the kind that the concerned are constantly able to engage in for social justice and the well-being of everyone. Thus, these programmes will also participate in education for global citizenship. They will make learners able to exercise their rights and fulfil their duties locally. This will in itself make people promote a better world, where the learners will have a clear conscience and the skills to achieve it.

We believe that the citizenship education announced by Cameroon will render the youth critical and more accountable; attitudes that will enable them in the future to enter global citizenship. But this will require a better reform of the education system than the superficial ones we know from the past (cf. Foaleng 2014). Because, just as adult education through community approach, education for citizenship must be transformative. We cannot use traditional teaching methods, which are limited to “knowledge transfer”, for that. We believe that we should enter a transformative learning system, making use of transformative pedagogy that leads to real personal and social change (cf. Sterling 2014). This in turn is another major challenge for Cameroon to face: to have consequently qualified trainers. And that is another story.

Cameroon (2015): Examen national 2015 de l’EPT. http://bit.ly/1B7EUzN

Falk, R. (1993): Making of global citizenship. In: J. Brecher, J.B. Childs, J. Cutler (ed.): Global Visions. Beyond the New World Order, 39 –52. Boston: South End Press.

Foaleng, M. (2002): Bildung in postkolonialer Gesellschaf t. In: W. Friedrichs/O. Sanders (Hg.): Bildung/Transformation. Kulturelle und gesellschaftliche Umbrüche aus bildungstheoretischer Perspektive, 201–216. Bielefeld: Transcript.

Foaleng, M. (2014): Réforme éducative et formation des enseignants. In: Syllabus Review, Vol. 5, 55–74.

Fondation Education et Développement (2010): Education à la citoyenneté mondiale. Un guide pédagogique. http://bit.ly/1Ijc44i

Forum Mondial de l’Education (2000): Cadre d’action de Dakar. L’éducation pour tous: tenir nos engagements collectifs. Paris: UNESCO.

Ghosh, S. (2015): Learning from community: Agenda for citizenship education. In: Education, Citizenship and Social Justice, Vol. 10(1) 21–36.

Metote, C. (2012): Les entreprises camerounaises au défi de la responsabilité sociale. In: T. Atenga, G. Madiba (dir.): La communication au Cameroun: les objets, les pratiques, 9 –20. Paris: Editions des archives contemporaines.

Seukwa, L.H. (2007): The ingrained art of sur vival. Köln: Rüdiger Köppe.

Sterling, S (2014): Separate Tracks or Real Synergy? Achieving a Closer Relationship between Education and SD, Post 2015. In: Journal of Education for Sustainable Development, 8(2), 89 –112.

UNESCO (2013): Education à la citoyenneté mondiale. Une nouvelle vision. http://bit.ly/1G3uZ3I

Dr. Michel Foaleng, Senior Lecturer in Sciences of Education, Trainer at the Higher Teacher Training College in Yaoundé, was Director of the Higher Institute of Pedagogy in Bandjoun and Dean of the Faculty of Education at the Evangelical University of Cameroon. He is currently Director of Academic Administration at the Université des Montagnes in Cameroon where, since 2011, he is also responsible for evaluating teachers.

Contact

P.O. Box 1116

Bafoussam

Cameroon

mfoaleng@udesmontagnes.org

foaleng@web.de

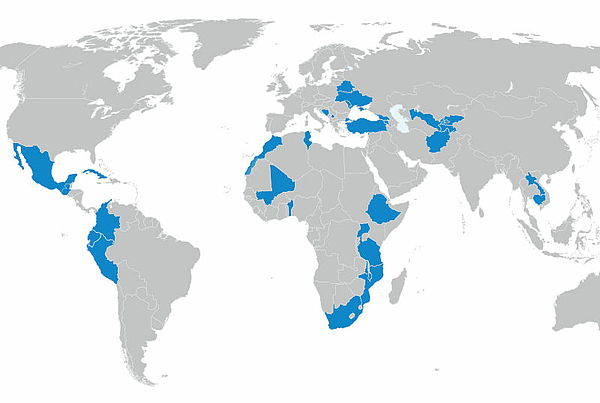

DVV International operates worldwide with more than 200 partners in over 30 countries.

To interactive world map