In Japan, there has been an upsurge of privatization in the field of adult education. This began slowly in the1970s, and picked up pace after 2003. What are the reasons for this development, and above all, what are the consequences of such an education policy? Joko Arai reports. Joko Arai is a Professor in the Faculty of Social Sciences, Hosei University in Tokyo, Japan.

Outsourcing of adult education began in Japan in the 1970s for the purpose of "rationalizing" administration. But the number of cases was small and the organizations used were purely non-profit third sector or community organizations.1 But after the 2003 amendment of the Local Autonomy Act and the granting of permission by the Ministry of Education and Science in January 2005, some municipal governments started to outsource the whole management of some public adult education institutions to private profit-making organizations in 2006. The number of cases of outsourcing in adult education has recently been rising.2

There are two reasons for recent outsourcing of adult education. One is the crisis in the public funding of municipalities brought about by the decentralization policy of central Government under the De-centralization Act passed in 1995. The Government launched its decentralization policy in order to reduce national public expenditure. It also argued that there was a "democratic" case for moving responsibility for many areas of administration to local government. But in fact the central Government interfered in the financial arrangements of municipalities, claming that it would support them after reducing central financial support by introducing widespread deregulation. Because of their need to reduce their own financial expenditure, and in accordance with instructions from central Government, municipal governments had to introduce outsourcing policies in many fields including adult education.3

The other reason is the entry into the adult education and lifelong learning market of private corporations. This is the result of the Lifelong Learning Promotion Act enacted in 1990. This was aimed at the Ministry of Education, the Ministry of International Trade and Industry, and at prefecture governments. But as a result of the financial crisis and the instructions issued by central Government, it has encouraged municipal governments to outsource their adult education services to civil society organizations, and to provide no support except some contractual funding.

We can see the results of these outsourcing policies in two ways. Although governments have introduced some outsourcing of adult education, they have kept some kinds of adult education for them-selves: for example, family education, adult education related to community involvement and so on. Vocational education is usually included, though it is not called adult education in Japan. Adult education is thus separated into two areas by governments, one public and the other private.

This division has also resulted in the introduction of external controls into adult learning and education.

In the area retained by government, activities tend to focus on specific purposes, apart from the broad humanistic and synthetic approach. Governments use adult education directly for administrative purposes, and sometimes they move adult education from their education division to others such as community affairs. Adult education staff are usually compelled to adapt their practices to purposes other than education in spite of their genuine wish to carry out adult education.4 In such cases, political control by national as well as local government easily influences adult education practice. The recent strong will of central Government to exercise control is seen in both the 2000 amendment to the Social Education Act and the 2006 total revision of the Fundamental Education Act in Japan.5 This political tendency at national level has already influenced and will increasingly influence municipal government policies through outsourcing in the public area of adult education.

In the area abandoned by government, practice tends to be con-trolled more by market mechanisms. The organizations that provide adult education services are usually subject to market forces, even in outsourcing, because governments do not usually allocate sufficient money in contracts. Local governments usually want to satisfy local residents and therefore monitor the activities outsourced by them. But they only do this at a distance, by checking such things as the quantity of services delivered or the number of participants, in the same way as market mechanisms. Organizations therefore seek to reduce both the number of adult educators and the levels of their salaries as far as possible in their financial management. They also require adult education staff to match their activities to the market.

In this situation, and because the organizations which employ them are usually not given long-term outsourcing contracts, the employment conditions of adult education staff are very unstable. They may engage in adult education without direct government control, but they do not have jobs for life because of both their low salaries and the instability of their employers. Moreover, they cannot easily pursue good-quality adult education because of the request for them to comply with market forces.6

With the reduction of public facilities and public support for learning activities, and without good educational support to encourage them to learn by themselves, people tend to feel that it is natural to pay almost all their own expenses for their learning activities, and think of these as consumer goods.

If we look at the history of adult education in Japan after the Second World War, we see that people's adult education movements have led to improvements in the professionalism of adult education staff. Such staff, who have usually been in stable public employment, have explored the philosophy and methods of adult education by living and thinking together with people in each community. These practices have expanded the base of adult education movements.7

By comparison with this historical development, recent outsourcing policies in Japan are dangerous, to the point of losing sight of the importance of adult education staff and their freedom of practice.

We must make public support for adult education stronger, even under outsourcing policies. In order to do so, we have to work in two dimensions. One is the field of adult education funding, and the other is the system of adult education staffing.

In terms of funding policy, we have to request more appropriate budgets for adult education from governments at every level from municipal to national. To achieve this, we must explain to both people and government the importance of adult education for people's lives, regardless of market mechanisms and global economic competitive ideology.

We also need to propose and monitor ways of using the budget. Whether through outsourcing or not, we need to ask governments to introduce and enforce proper regulation, and we may have to participate in creating such a regulatory framework, in order to achieve a good quality of adult education.

Furthermore, organizations wishing to undertake adult education on behalf of government need to network among themselves in the same way as a trade union, and with learners and people in general, in order to engage in a movement for regulating the quality of adult education. They will then be able to use such regulation in bargaining with government.8

If this philosophy and this regulatory framework are to be realized in practice, we must pay more attention to the system of adult education staffing. Adult education and lifelong education cannot develop without dialectical debate not only among learners but also between learners and educators.

Educators are not people who control learning in one way only, or provide an automatic response to requests from learners. They try to understand people in the community where they work, and to identify problems in their community at a general level together with learners. They try to devise activities in which people can think about such problems together with them.

Sometimes, movements to overcome such problems arise out of such practices. And it is through a stable employment system that adult educators can realize and continue such good quality practices and can explore ways of improving them. Adult education has to provide more stable employment and the system needs to be improved so that it keeps the good will of staff and their ability to deliver and explore good-quality practices in adult education.

We have experience of a few movements to improve working and employment conditions for adult education staff from the 1960s to the '90s in Japan.9 But these were before recent outsourcing. We now need to re-examine both the system and the possibilities for creating a good system of adult education employment. We need to look at all current employment situations, such as permanent public employment, part-time and temporary contracts, private employment, and soon.

1 Some municipalities like Kitakyushu-shi outsourced the management or services of some adult education institutions, such as libraries and Kominkan (Kominkan is our traditional public adult education institution at community level) to the third sector. There are other municipalities which outsourced their management or services to community organizations. They introduced such policies for the same reason of "rationalizing" administration, sometimes with the false ideology of decentralization. The number of these municipalities was not large, and the organizations that undertook such management work were purely non-profit. These policies enabled municipalities to reduce the number of their regular staff in the adult education field.

3 The Government introduced "guidelines for promoting administrative reform of municipalities for decentralization and a new era" in 1997. It also issued an amended version in 2005. Through this new version, central Government compels local governments to comply with the prescribed way of managing all public institutions, outsourcing management of public or semi-public organizations to more private organizations.

4 Governments usually tend to cut employment costs in order to reduce local government finance. They do so by reducing the number of public employees or by changing employees' conditions from permanent full-time employment to part-time or temporary contracts. They usually keep some regular staff in the areas for which they retain responsibility, but they do not usually respect their specific abilities in adult education. They employ part-time or contract workers in areas that they regard as having low priority.

5 For example, the Social Education Act abandoned "support without control", and introduced the words "family education" and "charity work and activities for young people" into some articles of the 2000 amended version. "Family education" is mentioned in no less than three articles. The 2006 total revision of the Fundamental Education Act also introduced the words "family education", and "love for the state and the home town", into the purposes of education.

6 Some meetings and conferences about outsourcing in adult education have been held by JAPSE (Japanese Association for Promoting Adult Education), JASSACE (Japanese Society for Study of Adult and Community Education), and the Japanese Society for the Study of Kominkan, etc. We already have a few reports (for example, the monthly journal Social Education No. 610, August 2006, featured this problem and carried reports of some cases). JAPSE published a booklet about this problem in August 2006. But there is as yet no full case study.

7 Under the spread of "urban city management" many local governments have been appointing staff under short-term contracts for as little as three years since the1980s. Around 1990, governments ceased expecting staff to have special abilities in adult education. Before then, they had usually required staff engaged in adult education to have qualifications in adult education or social education. These specialists were able to stay in adult education posts for over ten years if they wanted. Some municipalities employed staff specifically to manage adult education from the 1960s following amendment of the Social Education Act in the 1950s; other staff were appointed as a result of residential adult education movements and the actions of political movements in the 1970s or even the late '80s. But the number of such municipalities is now much smaller. Such specific staff have usually continued to engage in and explore adult education practices for many years. But in some cases, they have been unfairly transferred, giving rise to protests. See Annexe 2.

8 T his idea comes from the community agencies movement supported by trade unions in Ontario, Canada. This network has made proposals to government for community work in general, and particularly for funding methods. See the paper "Building Strong Community A call to reinvest in Ontario's nonprofit social services", January 2004. The information about this movement comes from the community worker program group of George Blown College in Toronto.

| classification | total | Kominikan (including similar institution) | Library | mu- seum | similar institutions to museum | institution for young people | institution for women education | institution for community sport | cultural hall |

| public institution (but about institution for community sport, figure expresses the number of organization) | 56,111 | 18,173 | 2,955 | 667 | 3,356 | 1,320 | 91 | 27,800 | 1,749 |

| total | 8,005 | 672 | 54 | 93 | 559 | 221 | 14 | 5,766 | 626 |

| proportion of entrusted institutions to total number of public institutions in | 14,3% | 3,7% | 1,8% | 3,9% | 16,7% | 15,4% | 20,7% | 35,8% | |

| prefecture | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| municipality | 268 | 1 | 2 | - | 35 | 14 | - | 211 | 5 |

| association by plural municipality | 123 | 1 | - | - | 18 | 2 | - | 98 | 4 |

| corporation regulated by the 34th article of the Civil Law in Japan-semi- public | 5,207 | 243 | 36 | 86 | 382 | 156 | 7 | 3,749 | 548 |

| other (ordinal) | 532 | 15 | 8 | 3 | 46 | 14 | 1 | 117 | 12 |

| non profit organizations | 165 | 4 | 7 | 1 | 9 | 14 | 1 | 117 | 12 |

| other | 1,710 | 408 | 1 | 3 | 69 | 21 | 4 | 1,170 | 34 |

Note: An entrusted organization means an organization entrusted under the rule of Clause 3 of Article 244-2 of the Local Autonomy Act now in force in Japan, or under the same clause of the Act before amendment.

This table is translated from the original written in Japanese. Information is compiled by the Ministry of Education and Science every three years on the basis of regular social education research, and the above data is from the 2005 collection. The table is taken from the Ministry website.

(Workshop: The Right of Action of the Right to Learn on 30th January in WSF2005)

Yoko Arai (Japanese Association for Promotion of Social Education, JAPSE)

The Constitution, the Fundamental Education Act and the Social Education Act guarantee the right to learn, including freedom of learning.

In Japan, municipalities have employed many adult educators as public servants. Sometimes, municipal governments have tried to control their work, especially in the field of political education. Government then requires them, either through the Education Board or directly, to stop their work and in extreme cases transfers them to other positions.

We have had a lot of such cases since the late 1950s. Over time, politicians have become more skilled at hiding the political will to control. For example:

a) 1968 in Urawa city

When the children's group in a Kominkan tried to publish an article about the Vietnam War in their newspaper "Chibikko Shin bun", the Education Board stopped it and transferred the social education staff working in the Kominkan because it was opposed to their ideas.

b) 1990 in Tsurugashima city

Twelve social educators were suddenly transferred to non-eductional positions from the Kominkan. They had been helping people to learn and to become active.

c) 2000 in Hoya city

Some social education staff in Hibarigaoka Kominkan were suddenly transferred to non-educational positions. They even included specialists in social education. This was because of a problem caused by the consolidation of municipalities.

Because of problems of finance, some municipalities have changed the employment conditions of social education staff from full-time to part-time. This tendency has continued since the late 1970s, and has recently grown stronger. Local governments have often implemented these policies by moving the management of the social education institute where staff are employed from the public to the private sector.

Some municipal governments have tried to move management of social education institutes such as Kominkan from the Education Board to the head of the government.

In many cases of transfer, the staff concerned have objected to the public employment court, and local residents who are learners have helped them by setting up support groups and movements. Some-times they have won their cases and have been able to return to social education work.

For example, in Tsurugashima-shi, over ten thousand residents signed a petition and 150 people came together and formed the Group for Protection of Social Education of Tsurugashima. They had numerous meetings and published news of this violation, to support the court action. After three years, the staff were able to return to social education work. Afterwards, they published a book reporting on the movement.

In these court disputes, we have used the existing three laws, especially the Fundamental Education Act and the Social Education Act. We have made clear the importance of specialist social education staff for people's right to learn.

In some cases, local residents who are learners have prevented a shift in management authority from the public to the private sector through mass movements. They have researched and gathered a lot of relevant information. They have held large meetings and have lobbied not only the Education Board but also the municipal council.

In some cases they have been successful, despite the difficulty of preventing such changes. However, employment conditions for social education staff have not improved and have become less stable.

In the case of Okayama city, for example, the movement was successful. In the 1980s, most social education staff in the Kominkan were made part-time employees. But after a few years, some of these part-time staff started to learn about the theory and history of social education. Full-time social education staff helped them by using support from national movements for social education like JAPSE (Japanese Association for Promotion of Social Education). Part-time staff were empowered by a political and democratic view of social education practice. As a result, their educational activities in each Kominkan at community level were thought important for residents. The local government of Okayama city also began to think their work necessary and important for the management of the city, and employment conditions became more stable than before.

In almost every case of the unfair transfer of staff or the transfer of management authority to the private sector, JAPSE has gathered information and helped the movement opposing such developments. In order to help these movements, it has set up a special research team, which has interviewed the institutions concerned, including the administrators, and has published information reports. It has built up experience of action movements.

The Social Education Act has been amended many times since it was first adopted. On each occasion, we have analysed the changes and sometimes we have protested. Even after bad changes, we have put forward ideas for practices that would protect the right to learn, especially freedom of learning, by using the Fundamental Education Act.

The Social Education Act is subsidiary to the Fundamental Education Act, so that we have to work within the terms of the latter. However, there are recent policy moves to amend the Fundamental Education Act itself.

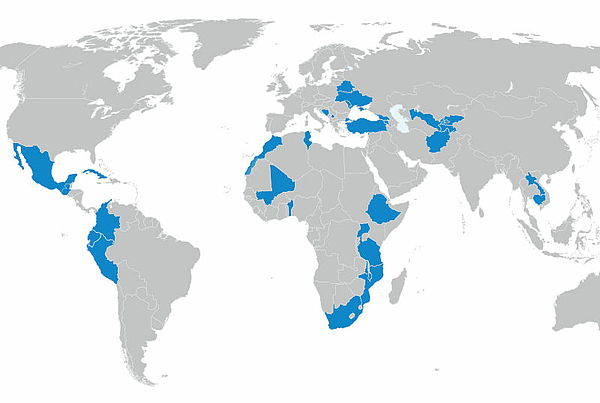

DVV International operates worldwide with more than 200 partners in over 30 countries.

To interactive world map