At present, in line with the overall financial and socio-economic crisis, the Slovenian adult education is facing difficulties. In spite of the high EU indicator value1 on “Participation of 25 to 64 year-olds in lifelong learning” (formal, non-formal and informal education and training) ranking Slovenia sixth in the EU (and first among the younger member states), adult education experts have been trying to draw attention to structural problems hidden behind this favourable result. All the more so, since it gives policy-makers the wrong message: that no immediate incentives, especially financial ones, are called for in the field. In reality however, adult education is confronting several challenges that need to be addressed by joint efforts from all stakeholders. Before getting engaged too deeply in the current situation, let us see whether anything could be learned from the past, dating back twenty years and more.

Slovenia is a small Central European country (surface area 20.273 km2, pop-ulation approx. 2 Mio) located on the edge of the Balkan Peninsula. Formerly part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and after 1945 one of the six constituents of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugo-slavia, Slovenia obtained international legal recognition of its independence in 1991. It then began rapidly to carry out the transformation of its political, social and economic system from one-party political dictatorship and a system of social self-management to parliamentary democracy and a market economy. As a matter of fact, the transition process had been taking place in the late eighties, leading to the first free parliamentary elections in 1989, and then continued in the nineties.

The attempts at political, economic and cultural liberation of the country certainly affected processes in the field of adult education (AE). Interestingly, the sector’s situation in the eighties was quite paradoxical: on one hand, strategic documents on socio-economic development envisaging a rapid development of the young country emphasised the need for better educated human capital. It was clear that this goal could not be obtained quickly and efficiently enough by improving the education system for children and youth only. Therefore, the importance of adult education was acknowledged, and the need for adequate supply was strongly emphasised.

On the other hand, after a relatively flourishing period marked by adult education being porated in strategic papers an independent field oriented mainly towards vocational education and training as well as socio-political education for self-management, adult education experienced a severe crisis, based mainly on two regrettable ideological orientations:

Resulting from these concepts and due to seemingly progressive educational reforms, the Slovenian AE system was theoretically well-off. In practice this was not the case: first, the network of adult education providers deteriorated seriously – adult education centres, i.e. so called “workers universities” or “folk high-schools” – were not allowed to deliver formal AE anymore, schools were short of proper know-how for educating adults, and educational centres within work organisations suffered from lack of funding. Secondly, expert centres at national level (the Association of Workers’ Universities, the Adult Education Unit at the National Education Institute, and the Association of Educational Centres of Slovenia) which had taken care of the conceptualisation, development and implementation of adult education were abolished, i.e. their financing ceased or was severely reduced. Clearly, the adult education sector was not in good shape when it was expected to face the serious challenges that began to manifest themselves with the rise of the new state.

Nevertheless, in 1984, a dedicated group of professionals, gathered in the Slovenian Adult Education Association, in cooperation with individuals vested with social and political functions, triggered the formulation of a long-term programme of adult education development and gradually started to implement it, both through research dealing with concepts and strategies in AE, and through the introduction of new, practical approaches.

Slovenian Adult Education in the Nineties

1991 was a very important milestone not only in Slovenia’s history but also in its adult education. Noteworthy from that period is the publication “Education in Slovenia for the 21st Century: Adult Education (1991)” in which AE was defined as an independent field for the first time in Slovenia, and expert grounds for its further development were laid. At that point and throughout the first half of the nineties, some fundamental developments in different areas can be observed:

These developments were backed by an urgent need to introduce measures that would contribute to the improvement of the educational and qualification structure of the population. According to statistical data, in 1991 around 50 % of the labour force and approximately 40 % of the employed were practically without formal qualifications. As a result of a growing demand, the regional distribution of adult education providers and programmes spread. It was markedly enlarged by many emerging private providers.

In support of the adult education network, the Slovenian Institute for Adult Education (SIAE) became the indispensable umbrella institution connecting and balancing key interests of various stakeholders, and mediating them to the responsible state authorities. The Institute combined professional arguments with the needs and opinions of main actors in the field, including civil society, thus promoting the development of the adult education system and practice. SIAE’s standpoints were underpinned by international comparative studies which substantiated the need of the state to ascertain stable conditions for the accelerated development of adult education thorough its measures and regulations.

The conceptual foundations for the development of AE were laid out by the “White Paper on Education and Upbringing” (1995), and elaborated further by the umbrella Act, the “Organisation and Financing of Education Act” (1996), which defines the aims of the whole education system and the ways of its organisation and financing. In the same year a package of five special acts was issued, each regulating one of the educational subsystems according to either level or field of education. One of them is the “Adult Education Act”, the overall law regulating common characteristics of adult education, thus confirming its position as an independent field and its inclusion in the system of public financing. This Act introduced the concept of an Adult Education Master Plan as the basis for positioning and financing AE provision and especially to create a balance between education and training for work on one hand, and more general adult education directed to personal and community needs on the other hand.

In the late nineties, preparation of the expertise needed for the final preparation of the Adult Education Master Plan (AEMP) was carried out. Meanwhile AE was financed via public tenders with the professional support of SIAE, and in line with its attempts to introduce new forms and methods in AE as well as new approaches to AE programming. As a result of analyses that had shown discrepancies affecting educationally deprived categories of population, special attention was being paid to the introduction of innovations in the field of non-formal AE. These endeavours were envisaged to counteract the supply generated by the private AE sphere, which had blossomed in the period of transition and mainly developed education programmes for the relatively well-educated part of population and of high market demand.

Without doubt, the adoption of the “Resolution on the Adult Education Master Plan (AEMP) until 2010” was one of the most significant achievements in the field of adult education in Slovenia. It was the final step in a nearly ten-year process of preparing the grounds for a new adult education policy and practice, designed to assure balanced and stable development of the field.

Above all, the AEMP was designed as a strong incentive for the increase of investment by all adult education stakeholders – individuals, community, enterprises and state. It was meant to link a range of actors in order to shape an effective environment at the national level. The AEMP defined goals (and benchmarks), priority fields, activities and the approximate extent of public funds for AE in three fields:

It also encompassed infrastructural activities, such as the professional development of adult educators, quality issues, information and guidance, research and development projects, information and promotion services, etc.

Since 2005, the implementation of the AEMP and its concrete funding has been determined by the Annual Adult Education Programme (AAEP), adopted by the government and previously coordinated with the governments consultative body, i.e. the Adult Education Expert Council (in charge of organisation, quality and efficiency of AE). The subsequent organisation of education is defined in annual plans of organisations which carry out adult education according to publicly valid educational programmes. Adults are enabled to participate in individual programmes on the basis of public tenders.

Since Slovenia joined the EU, the European Social Fund has become an additional source for financing adult education. These funds have been channelled into developmental projects furthering mainly higher educational achievement and employability, literacy, training of adult educators, quality, and information and guidance in adult education.

The implementation of the AEMP and subsequent Annual Programmes is meant to be subject to thorough monitoring, analyses and reporting to the National Council. However, due to its huge complexity, endeavours for setting up an adequate information system are just beginning to bear first results. Findings stemming from the latter may confirm (or not) the coherence of the AEMP structure and above all reveal the (in)efficiency of its translation into AE practice.

The system of AE, especially its regulation, governance and financing, is subject to rethinking with regard to the sufficiency of funds, efficiency of their use, and equality of their distribution. In contrast to relatively good performance of Slovenian AE regarding EU and some national indicators, a more thorough examination reveals several structural issues stemming (also) from inadequate financing. Due to the lack of precise monitoring, transparency and accountability of AE financing, its efficiency as well as the estimation of its broader impact is presently undergoing debate. An additional obstacle to better performance of the AE (financing) system is the lack of proper infrastructure – the autonomous and high-quality development and research initially expected to be ensured by the Slovenian Institute for Adult Education.

A detailed presentation of all current issues would exceed the scope of this paper. Therefore let us mention only the most outstanding:

Like more than two decades ago, the Slovenian adult education system is facing a crisis that has its specific features and reasons, but is also part of a larger picture and therefore strongly embedded in the overall financial, socio-economic and cultural crisis of the country, and the whole world. Again, the AE sector could and should be engaged in measures that the country has been undertaking lately in order to overcome the present difficult situation.

Some principles that have guided the way before, but somehow got lost along the way, and some new ones, might be the following:

Obviously, the Slovenian adult education system has already proved its ability to respond proactively to challenging times and to act as one of the vehicles towards a better society and economy. The present crisis should be recognised as an opportunity for setting right some devious steps from the past, and attempting another breakthrough at an even higher professional and policy level.

Analiza uresni evanja Resolucije o Nacionalnem programu izobraževanja odraslih za leti 2005 in 2006 (Analysis of the Implementation of the Resolution on the Adult Education Master Plan for the Years 2005 and 2006), Vlada RS, Ljubljana 2008.

Bela knjiga o vzgoji in izobraževanju v Republiki Sloveniji (White Paper on Education and Upbringing in the Republic of Slovenia), Ministry of Education and Sport, Ljubljana, 1995.

Černoša, S., Bandelj, E.: Slovenian Adult Education in the Context of Lifelong Learning, Lline, 2007, Vol. XII, issue 4/2007, p. 243–251.

Drofenik, O. (et al.): Nacionalni program izobraževanja odraslih, Strokovne podlage zvezek 1, Razvojne usmeritve (Expertise on the Adult Education Master Plan Vol. 1, Development orientations) Slovenian Institute for Adult Education, Ljubljana 1998.

Drofenik, O. (et al.): Nacionalni program izobraževanja odraslih, Strokovne podlage zvezek 2, Cilji, dejavnosti, utemeljitve (Expertise on the Adult Education Master Plan Vol. 2, Objectives, activities and argumentations) Slovenian Institute for Adult Education, Ljubljana 1999.

Education in Slovenia for the 21st Century: Adult Education, Expert grounds, National Education Institute, Ljubljana, 1991.

Final Annual Account of the Ministry of Education and Sport Budget for 2005, 2006 and 2007.

Ivančič, A.: Inspiring story of adult education in Slovenia. Lline, 2003, Vol. VIII, issue 3/2003,

p. 50–55. Jelenc Krašovec, S. , Kump, S.: Sistemsko urejanje izobraževanja odraslih (System Regulation of Adult Education), Sodobna pedagogika Vol. 1/2009, p. 199-216, Ljubljana 2009. Jelenc, Z. (Ed.): Adult Education Research in the Countries in Transition : Research project report, Studies and Researches Vol. 6, Slovenian Institute for Adult Education, Ljubljana 1996. Progress Towards the Lisbon Objectives in Education and Training – Indicators and Benchmarks 2008 Report , Commission Staff Working Document, Commission of the European Communities, Education and Culture, Brussels, SEC (2008) 2293 (available at ec.europa.eu education/lifelong-learning-policy/doc1522_en.htm). Resolucija o nacionalnem programu izobraževanja odraslih do leta 2010 (Resolution on the Adult Education Master Plan until 2010), Ur. l. 70/2004. Strategija vseživljenjskosti u enja v Sloveniji (Strategy on Lifelong Learning in Slovenia), Ljubljana, 2007. Zakon o izobraževanju odraslih (Adult Education Act), Ur.l. 12/1996, 86/2004, 110/ 2006.

Zakon o organizaciji in financiranju vzgoje in izobraževanja (Organisation and Financing ofEducation Act), Šolska zakonodaja I, Ministry of Education and Sport, Ljubljana, 1996.

1 According to the “Progress towards the Lisbon Objectives in Education and Training – Indicators and Benchmarks 2008” Report, the Slovenian participation rate in 2007 is 14.8 % (EU average being 9.7 %); data source: EU Labour Force Survey.

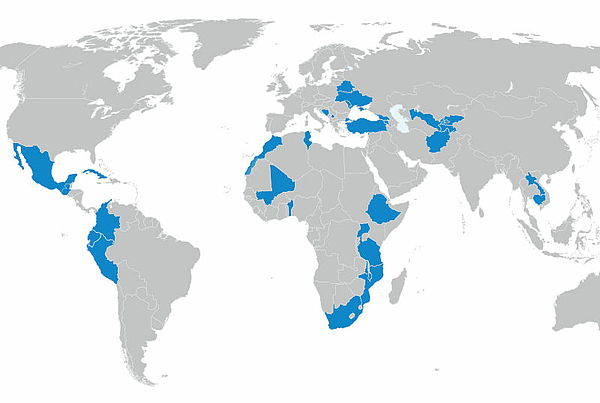

DVV International operates worldwide with more than 200 partners in over 30 countries.

To interactive world map