A growing body of empirical evidence from more than 30 countries suggests that making literacy and numeracy core components of education and training programmes for unschooled or insufficiently schooled young and older adults would accelerate progress towards achieving the Millennium Development and Education for All Goals. Neglecting to include these components in effect sabotages progress towards the goals.

Small-scale research efforts scattered over at least 32 countries since 1975 have been producing empirical evidence in support of the beneficial effects of including literacy as a component of training and education programmes for adults. This paper summarises the findings in terms of their bearing on the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). These involve poverty reduction, the abolition of hunger, universal primary education, gender equity and empowering women, substantially improved health in terms of infant and maternal mortality and the eradication of diseases, environmental sustainability, and even some approach to a better global society through partnership. All the member governments of the United Nations have pledged to achieve the MDG by 2015. If including literacy and numeracy in adult education and training can accelerate progress towards these goals, neglecting to include them is tantamount to sabotaging the main effort.

A word of caution about the research is in order, however. Although most of the research studies have been done since the mid-1960s, few of them, whether mainly quantitative, qualitative, or ethnographic, escaped imperfection in terms of scientific rigour, representative coverage or thorough analysis. Most programmes have not been able to maintain complete records of attendance, progress, dropouts, completion, and levels of attainment, let alone longer-term monitoring of the actual uses of skills, knowledge, reading and writing and the impact on daily living. Many, perhaps most, programmes have had to contend with some hostility and resistance to attempts to evaluate them. Few have been able to escape the ranges of findings and consequent ambiguities and apparent inconsistencies that characterise research into the behaviour of human beings.

The lack of proper baselines and control groups has enabled some to raise the following objection: What favourable evidence there is, is favourable only because the adults and youths who enrol in literacy programs are exceptional. Even though they are poor, they are more energetic than average, already more favourably disposed toward modernisation, and already know more than their non-literate neighbours. They are selecting themselves into the programmes and cannot be taken to represent their more average neighbours. The inference is that, if these participants are used to justify programmes for the general non-literate population, there would likely ensue much worse rates of enrolment, attendance, completion, and success – particularly in terms of usable and “permanent” skills in reading, writing, and calculation – and less than worthwhile longer-term changes of attitudes and behaviour. In short, support for progress towards the MDG would be much weaker than the available evidence might suggest.

Even if the proposition were accurate, it would not undermine the case for adult training programmes with literacy. On the contrary, it underlines the probability that the investments are actually reaching the right sorts of people: those who can best make the investments productive and reinforce progress towards the MDG. From the practical point of view of investment, then, the proposition would in fact help make the case for including literacy in development policy.

Nevertheless, it is worth pointing out that the proposition is probably wrong. Evidence from at least three “total literacy campaigns” in India shows that only a small minority of adult learners are unable to learn the skills of reading, writing and written calculation. The three campaigns recruited virtually all the non-literate adults of their areas and succeeded in teaching most of them at least enough to succeed at the official “graduation test”. They thus tended to vindicate the learning abilities of the average non-literate adult and to justify appropriate learning programmes.1

On the other hand, field studies nearly ten years after the campaigns did suggest that many, if not most, of the successful learners had largely forgotten how to read and write. The findings suggested either that the learners had not learned the skills to a “permanent,” usable degree or, finding no reason to practise their skills, had simply forgotten them. Why people should successfully make the effort to exercise their right to literacy but later apparently let the effort go to waste is an issue that will arise towards the end of this paper.

Whatever their shortcomings, the studies underlying this discussion represent a substantial advance on what was available before. They have at least striven to address the concerns of policy-makers and planners. Further, they come from 32 countries in several regions of the world: Bangladesh, Bolivia, Botswana, Brazil, Burkina Faso, Colombia, Ecuador, Ethiopia, Egypt, El Salvador, The Gambia, Ghana, India, Indonesia, Kenya, Mali, Mexico, Morocco, Namibia Nepal, Nigeria, Nicaragua, Pakistan, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Somalia, South Africa, Sudan, Tanzania, Thailand, Turkey, Uganda. They can thus be considered representative of larger proportions of the human race as a whole and not restricted to just one or two particular cultures.

John Oxenham

Source: Barbara Frommann

Before taking up the specific MDG, we can note the general support that comes from three World Bank studies of the rate of return on investment. From 1977 through to 1999, the Government of Indonesia borrowed money on interest-bearing terms from the World Bank to support its national literacy programme. In 1986, the World Bank examined the rate of return (ROR) on the investment: it found that the individual rate of return was 26 %. Thirteen years later, the World Bank did a similar study for the Ghana National Functional Literacy Programme, for which the government had borrowed money on interest-free terms. The findings were:

Ghana (1999) female private ROR 43 %; female social ROR 18 % male private ROR 24 %; male social ROR 14 %

Two years later, in 2001, in a project it was supporting in cooperation with the Asia Development Bank in Bangladesh, again on interest-free terms, the World Bank found that the private rate of return was 37 %.2

These calculations suggest that investment in adult education with literacy is in overall terms quite as productive as investing in primary, secondary or university education.

Do these “overall terms” have any implications for the more specific aims of the MDG?

MDG 1 – Eradicate Extreme Poverty and Hunger: “Do adult education programmes with literacy help to reduce poverty through improving the productivity of livelihoods and raising incomes, and do they help reduce hunger through enabling farmers – women and men, small and large scale – to make their land more productive for both subsistence and marketing purposes?”

Studies pertinent to the question are available from eight countries,3 but cannot answer the question definitively. On the negative side, the 1998/99 national household survey in Ghana suggested that, although level of schooling made a difference to earnings and income, literacy skills acquired through non-formal education did not definitely appear to do so in either waged or self-employment.

On the positive side, a statement by Carr-Hill et al. in their study of the effects of 20 years of literacy programmes in Tanzania will help set the general tone:

The main effect which may be attributable to literacy is the spreading of modern agricultural techniques in the rural areas…

The richer farmers were first to adopt the new agricultural techniques, openly attributing their success to the effects of literacy. Farmers in Ugwachanya stated that the primers were of direct, practical use. All farmers were enthusiastic about the methods pioneered by the richer farmers… Though the poorer farmers might not see the direct relevance of literacy, such examples of a horizontal transfer of information from the richer farmers can probably be attributed indirectly to the literacy campaigns.4

More directly, in Kenya, farmers who had graduated from literacy courses were much more likely to use hybrid seeds and fertilizers than their illiterate fellows,5 while managers in the SODEFITEX corporation of Senegal estimated that the literacy programme had helped its associated farmers to raise their productivity by six per cent.6

In Bangladesh, Cawthera evaluated the effects of the Nijera Shikhi approach in 1997 and again in 2000. His observations led him to conclude that the Nijera Shikhi approach to NFEA had engendered:

“A sustained and beneficial impact on livelihoods: …” Incomes have increased by amounts which are highly significant to people who earn below average incomes in one of the world’s poorer countries.

“A lasting impact on agricultural practices and on nutrition: …” Many of the women now have kitchen gardens and grow a wider variety of fruit and vegetables. They also rear more poultry. Some of this is traded and so raises household income while some is consumed within the household and improves vitamin and protein consumption.

“A sustained increase in savings and investment: …” Many of those engaged in entrepreneurial activities had saved and invested in capital assets in order to generate profit. Many of these people said they only thought of doing this as a result of their learning during the course.7

In their evaluation of three REFLECT projects in Bangladesh, El Salvador, and Uganda, Archer and Cottingham8 approach the issue of productivity and income through an examination of “resource management”, or making available resources more productive than they were previously. They are able to furnish examples from all three countries of how the process of that particular form of adult education with literacy had stimulated participants to reconsider and improve their uses of land, water, crops, and money (underlining the point that, to have effects on people’s behaviour, instruction in literacy should be combined with usable information and skills).

Quite apart from productivity in its normal sense and related to empowerment (discussed below) is the effect that some mastery of calculation engenders. In almost every study from almost every country, participants who became literate say that they can now handle money, especially paper money, more confidently. More important, they feel less vulnerable to being cheated in monetary transactions. This is a key gain for people who are micro-entrepreneurs: it enables them to begin managing their businesses on a sounder basis.

At this point, it is convenient to mention the “literacy second” approach. For example, the 10-country Grassroots Management Training Program of the World Bank Institute began around 1990 with training for non-literate women in basic business management, using non-literacy based methods. However, the programme eventually had to respond to a demand from the participants themselves for more systematic instruction in arithmetic, writing, and reading. Where it is used, this approach appears to be successful in building both literacy and livelihood skills.

The overall inference, then, is that literacy education does contribute to reducing both poverty and hunger.

MDG 2 – Achieve Universal Primary Education: “Does adult education with literacy raise demand for schooling, so that newly literate parents send their children, especially their girls, to school? Further, do they try to see that the children observe the requirements of successful participation?”

A number of studies have looked at the question of the influence of literacy education, particularly for mothers, on the schooling of children. Despite differences and variations, the general finding is positive. In several countries, high proportions of mothers, whether literate or not, had most of their children in school, which argues that the value of schooling is now apparent to all, whether literate or not. Nonetheless, all the studies found that higher proportions of mothers enrolled in literacy classes tended to have placed their children in school, than illiterate mothers not enrolled in literacy classes. Three further points were noted:

First, as the classes progressed, even higher proportions of mothers began to send their children to school. Second, enrolled mothers were more likely not only to send their daughters to primary school but also to want them to go on to secondary school along with their sons. Third, enrolled mothers were more likely to insist on their children’s regular attendance at school, to ensure that children did their homework, and to discuss their children’s progress in class.

In one remarkable instance, government primary schools in Uganda fed by communities that were participating in a literacy education programme increased their enrolments by 22 per cent. In comparison, schools for other communities increased theirs by only 4 per cent. In addition, communities that did not have government schools and had established their own, and were also participating in the literacy education programme, more than doubled their enrolments, with a particular increase in the proportion of girls. Further, one-third of the communities studied set up new nursery schools for their younger children and actually paid facilitators to run them.

On the other hand, it is fair to note that such positive developments were not universal. One study found only slight impacts, while the findings of another were mixed: some communities showed no change at all in school enrolments, while neighbouring communities raised their primary school enrolments by more than 50 per cent.

Discussion in a plenary session

Source: Barbara Frommann

An important inference for both the First and the Second Millennium Development Goals flows from this signal: if parental literacy greatly helps school attainment, then governments need to organise effective adult education or training programmes with literacy, because they would help make mainstream education more effective and thus more likely to enable people to reduce their poverty.

MDG 3 – Promote Gender Equality and Empower Women: “Do women who take part in literacy education programmes feel better able to improve the quality of their lives and the lives of their families? Equally important, do they tend to take stronger roles in organizing their communities to improve the quality of life in their localities and societies? Does literacy education in effect tend to strengthen civil society?“

In many countries, the majority of participants in literacy education programmes are women, and poor women at that. The reason is doubtless that girls from poor families generally have the fewest opportunities to go to and to continue in primary school and so form the majority of adult illiterate populations. Adult educators suggest that their participation helps these women to develop stronger self-confidence, to inspire greater respect among their family and community members, and to take more active roles in running and improving their communities. If that is so, literacy education programmes would certainly be promoting gender equality and empowering women. But what evidence is there that this is actually the case? A number of studies provide some data, most of it supportive.

The drift of the evidence can be characterised by Burchfield’s findings in Nepal,9 which compared three groups of women: those who had had no schooling or adult education (107 women); those who had had a basic six-month adult education (201 women); and those who had taken a three-month post-literacy course after their six-month basic experience. Two indicators measured confidence or empowerment: (1) perceptions that one is respected by family and community, and (2) confidence in stating one’s opinions to family and community. The findings were not dramatic, but certainly positive. Whereas 38 and 42 percent respectively of the basic and post-literacy courses believed they now had more respect within their families – and could give examples of what they meant – only 2 percent of the control group shared that belief.

On the second indicator, confidence in stating one’s opinions to family and community, the proportions of basic course participants asserting that they now had more confidence to do so were much the same as on the first indicator. In contrast, among the post-literacy course participants, a full 50 per cent claimed they were more confident in stating their opinions to the family and 44 per cent claimed the same in regard to the community. In sharp contrast, only 4 per cent of the control group felt their confidence had increased over the past year.

These percentages of reported change for the better are of course large. On the other hand, they also indicate that half or more of the “treatment” groups did not feel they enjoyed either increased respect from their families or more confidence before the community because of what they had learned. All the same, the minorities who did feel that they had gained respect within their families are substantial, not negligible.

In a later study, Burchfield reported more indirectly:

“According to studies sponsored by USAID, by 1998 nearly 1,000 advocacy groups had been formed by women who had increased their literacy skills (USAID 1998).1 These groups have undertaken a wide variety of actions on both individual and public issues. A 1997 sample survey showed that such groups have confronted a number of social problems including domestic violence, alcoholism and gambling . . . The advocacy groups have spoken out on national issues such as women’s right to own property, caste discrimination and trafficking of girls. Recognizing that access to income increases their decision-making role in the family and community, women have also demanded greater access to economic interventions.”10

In short, these studies suggest that participating in literacy education does enable many women to develop stronger confidence and determination to take more assertive roles in their families and communities. The gains are admittedly variable and by no means universal. On the other hand, neither are they negligible. They do tend to contribute to the achievement of the third Millennium Development Goal. More programmes combining education or training with literacy would then accelerate progress towards it.

MDGs 4, 5 and 6 – Reduce Child Mortality, Improve Maternal Health, and Combat HIV/AIDS, Malaria, and Other Diseases: “Do literacy education programmes assist the improvement of health as measured by the indicators of child mortality, maternal health and the reduction of disease?”

This section considers possible contributions of literacy education programmes to the three Millennium Development Goals that bear on health. There are studies that suggest that at least some of the graduates of such programmes do use the knowledge they acquire to improve the health of themselves and their families. The most interesting study was done in Nicaragua ten years after the National Literacy Crusade of 1980. It found that women who had learned literacy through the crusade enjoyed higher survival rates among their children than the women who had remained illiterate. Also, survival rates were higher among the children born to participating women after the crusade than among the children they had had previously.11 Similarly, Burchfield’s three-year study in Nepal found that participation and attainment in literacy classes did increase health knowledge, but by not very much more than other media such as radio.

In regard to HIV/AIDS, Burchfield’s study in Nepal found that participation in the literacy education programme showed clear superiority over reliance on other sources of information. Similar findings emerged from another programme in Nepal, “Girls’ Access To Education”: after nine months of tuition, adolescent girls in the programme showed greater gains in health knowledge than girls who had received their information from other sources.

As regards maternal health and norms on family size, graduates of literacy programmes in Kenya and Tanzania tended to know more about family planning, hold more positive attitudes toward it, and practise it more than those who had not entered the programmes. The overall message from the available studies then is that knowledge conveyed through literacy education programmes does tend to contribute towards the achievement of the Millennium Development Goals for health.

MDG 7 – Ensure Environmental Sustainability

Many of the literacy education programs reviewed have included aspects of environmental sustainability in their curricula. However, none of the evaluative studies has examined the outcomes of those contents on the practices of the learners involved. Assessing the contribution of literacy education to ensuring environmental sustainability is unfortunately not possible at this stage. However, given the experiences outlined in the preceding sections, it is almost certain that well conceived and delivered programmes of literacy education that incorporated the issues of environmental sustainability would enable large proportions of participants to develop informed views and take locally relevant action about caring for and conserving the environment.

Beyond the MDG, current trends toward more extended decentralisation, democratisation, and the nurturing of civil society and political participation raise the question whether literacy programmes contribute to these. A few observations suggest that such programmes can indeed promote these trends, although with the usual variable outcomes. For instance, a study in 1990 evaluated the outcomes of adult basic education in four provinces in Burkina Faso. It found many, but again not all, of the newly literate men and women undertaking roles in almost all the economic and governing bodies of their villages. Similarly, the SODEFITEX corporation in Senegal was pleased to find that the farmers – men and women – who had taken the literacy and numeracy course took up roles in managing the affairs and accounts of the producers’ cooperatives, and began to take control of the marketing of their products. In addition, many of them undertook to teach literacy classes of their own.

In less favourable conditions, a study in Bangladesh noted that local cultural norms can militate against the aims of literacy education. What prompted the observation was the institutional exclusion of women from active roles in community organisations other than their own class committees. Expecting such institutions to change overnight would be unrealistic. Nonetheless, within that set of social constraints, the women’s committees did become more active in pursuing their own programmes. In one case, for example, they wrote away and raised the money to have their own tube well dug.

In sum, the message is that suitably organised and implemented literacy education programmes do tend to promote stronger and more confident social and political participation by poor, unschooled people, particularly poor women.

An unexpected potential benefit from literacy education is signalled by studies in Mexico and Nepal. Apparently, illiteracy can prevent people from understanding messages broadcast by radio, because an illiterate person tends to be dependent on a concrete and personal context to which to relate language. There appears to be a strong correlation between listening and reading skills, which suggests that it is not easy to circumvent the obstacles of illiteracy by offering health information over the air. The studies showed that the women with the weakest or non-existent skills in literacy had the most difficulty in understanding messages broadcast over the radio.

Reciprocally, targeted radio programmes can enhance the learning achieved in literacy programmes. This is the conclusion of an evaluation of a project in Ghana to reinforce the country’s functional literacy programme with a radio component: it found that enrolments, waiting lists, attendance, retention, and knowledge gains were all enhanced by the radio contributions.

The evidence set out above confirms the importance of including literacy and numeracy in adult education and training: without them progress towards the MDG will be slower. However, it is equally important not to regard such inclusion as a miracle-working ingredient. The evidence also underlines three cautions:

First is the well known pattern of behavioural change that Everett Rogers observed among farmers nearly 50 years ago: new information does not automatically or immediately change attitudes; and attitudes do not automatically or immediately change behaviours. People take time to absorb the implications of new information and, even after absorbing it, take even more time to put the implications into action. The process of personal change can be slow and unpredictable.

The second caution reflects the fact that people do differ. Change begins with minorities of people, perhaps only 20 per cent to begin with, then gradually affects others and spreads to majorities. Literacy and numeracy only help to make the process quicker.

The third caution is that education, training, literacy and numeracy depend for their full effects on supportive environments – social, political, institutional, infra-structural. They need to be part of a total development effort.

This paper has considered the case for promoting and investing in literacy as a central component of education and training programmes for adults. The evidence it draws on suggests that achieving the Dakar educational goal of a 50 per cent improvement in levels of adult literacy by 2015, especially for women, and equitable access to basic and continuing education for all adults would support and even accelerate the achievement of the Millennium Development Goals. Neglecting literacy education would be tantamount to undermining efforts along other dimensions, such as achieving universal primary completion, diversifying agriculture and raising its productivity, raising levels of health, and training for all forms of employment.

Acknowledgements: The material presented in this essay was collected through work for the World Bank, the UNESCO International Institute for Educational Planning and DVV International.

1 ASPBAE, 2000, “Reading the Wor[l]d: Understanding the Literacy Campaigns in India”, Malavika Karlekar, ed., Mumbai, ASPBAE (Asian South Pacific Bureau of Adult Education); External Evaluation Team,1993, “The Final Evaluation of the Total Literacy Campaign of Ajmer District”, A Report Conducted by the External Evaluation Team (mimeo) Delhi.

2 World Bank, 1986, “Indonesia Project Performance Audit Report. First Non-formal Education Project, June 30, 1986.” Report No. 6304. Operations Evaluation Department, Washington D.C., p. 16.

World Bank, 1999, “A Republic of Ghana, National Functional Literacy Program, Project Appraisal Document, May 18, 1999”. Report No. 18997-GH. Washington D.C., p.11.

World Bank, 2001, “Bangladesh Non-Formal Education Project. Project Status Report for June 4-June 25,

2001”, dated August 21, 2001, Washington D.C., p. 49.

3 Bangladesh, El Salvador, Ghana, Kenya, Mexico, Senegal, Tanzania, Uganda.

4 Carr-Hill, R.A.; Kweka, A.N.; Rusimbi, M., Chengelele, R., 1991, “The functioning and effects of the Tanzanian literacy programme”. Research Report N° 93. Paris: IIEP-UNESCO, p. 324.

5 Carron, G., Mwiria, K., Righa, G., 1989, “The functioning and effects of the Kenya literacy programme”.

Research Report N° 76. Paris: IIEP-UNESCO, p. 173, Table IX.6.

6 Oxenham, J., Hamid Diallo, A., Ruhweza Katahoire, A., Petkova-Mwangi, A., Sall, O., 2002, “Skills and literacy training for better livelihoods”. (Human Development Working Paper Series).Washington, DC: World Bank Africa Region, p. 27.

7 Cawthera, A., 2003, “Nijera Shikhi and adult literacy: Impact on learners after five years”, published on the World Wide Web at: www.eldis.org/fulltext/nijerashikhi.pdf, pp.14-15.

8 Archer, D. and Cottingham, S., 1996, “Action Research Report on REFLECT”. London: Overseas Develop ment Administration, p. 63ff..

9 Burchfield, S.A., 1997, “An analysis of the impact of literacy on women’s empowerment in Nepal”. ABEL Monograph series. Washington, DC: Academy for Educational Development.

10 Burchfield, S., Hua, H., Baral, D., Rocha, V., 2002, “A longitudinal study of the effect of integrated literacy and basic education programs on the participation of women in social and economic development in Nepal”. Boston, Massachusetts: World Education / Washington, DC: United States Agency for International Development Office of Women in Development.

11 Sandiford, P., Cassel, J., Montenegro, M., Sanchez, G. 1995. “The impact of women’s literacy on child health and its interaction with access to health services”, in: Population Studies, 49(1), March.

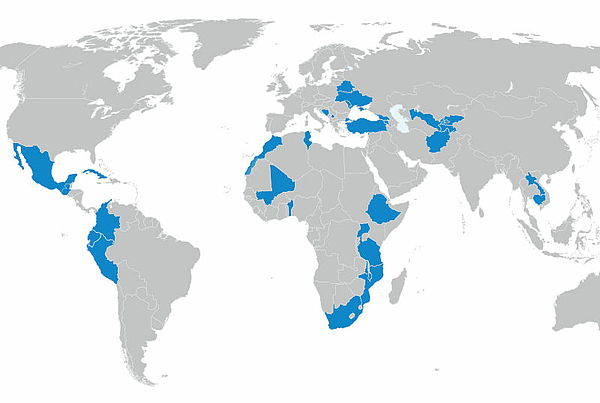

DVV International operates worldwide with more than 200 partners in over 30 countries.

To interactive world map