In 1989, the National Federation of UNESCO Associations in Japan (NFUAJ) launched the World Terakoya Movement. A Terakoya is an educational institution for people including literacy classes that were actively operated from the 17th to the 19th century in Japan. Anybody could attend learning activities at a Terakoya, regardless of gender and social status, and nationwide expansion of Terakoya contributed to a high literacy rate in Japan even before the introduction of the modern educational system. The movement which has been supported by Japanese donors is now implemented in Asian countries such as Afghanistan, Cambodia, Nepal, Laos and India. An example of this is the description of the “Angkor Community Learning Centre” Cambodia, in Siem Reap Province. Chiharu Kawakami is Director of the Education and Culture Department of the National Federation of UNESCO Associations in Japan (NFUAJ).

“Since wars begin in the minds of men, it is in the minds of men that the defenses of peace must be constructed.” In 1947, a group of people moved by this principle from the UNESCO Constitution formed UNESCO Associations in various regions in Japan. This was the world’s first spontaneous non-governmental movement that was formed upon UNESCO principles to conduct activities to promote peace based upon efforts to foster mutual understanding. The pioneers who started this UNESCO movement aimed for Japan to be a member state of UNESCO and reborn as a peace-loving country. The movement played a role in helping Japan join UNESCO in May 1951, five years before its admission to the United Nations and even before the signing of the San Francisco Peace Treaty.

In the years since then the movement expanded still further, and today 273 UNESCO Associations and clubs in Japan and approximately 3500 Associations and clubs throughout the world carry out volunteer activities in the regions where they’ve taken root.

Since 1969, while carrying out regional volunteer activities, the NFUAJ has also engaged in the UNESCO Co-Action Program for exchange and cooperation activities with citizens in other countries.

In 1989, one year prior to the International Literacy Year, the NFUAJ launched the “World TERAKOAYA Movement (WTM) ”. The main objective of the WTM is to end the cycle of poverty und illiteracy, provide people with knowledge about health and hygiene as well as an understanding of their rights, and to improve individual quality of life. At the same time, through this international cooperation to promote partnerships and education for international understanding for the purpose of achieving a global society where everyone can mutually learn about each other’s societies and cultures and share the joys of learning and living together.

The amount of annual support, donation from the Japanese citizens, organiza tions, private sectors, schools, etc for each year is about one hundred million yen (approx. 1 million US Dollars). At present having our branch offices both in Af ghanistan and Cambodia we conduct the WTM in Afghanistan, Cambodia, Nepal, Laos and India, all of which adopt the Community Learning Center model in their operations. In this article, I would like to feature the programs called “Angkor CLC project” undertaken in Siem Reap province in the Kingdom of Cambodia.

The UN began peacekeeping operations in Cambodia in 1992, following the protracted internal conflict there. The UN Volunteers Program (UNV), the UNESCO Cambodia Office, and the NFUAJ decided to implement the Community Temple Learning Center (CTLC) Program as part of the plan for reconstruction of Cambo dian society. We agreed that the dispatch of experts required by the program would be handled by the UNDP-UNV, the total operating cost of the program would be handled by the World TERAKOYA Movement of the NFUAJ, and that actual opera tions would be implemented by a TERAKOYA Unit to be established at UNESCO Cambodia Office (and staff also to be dispatched later).

The purpose of this CTLC Program was to cooperate with efforts to rebuild the functionality of education that takes place outside schools in the local communities. In acting as a support for literacy education, this out-of-school educational function ality will help regional societies to become able again to act for themselves and carry on the educational activities needed by those communities. It was decided that programs should be implemented in Battambang Province and Siem Reap Province, where returning refugees are concentrated.

The project was handed over to the Department of Non-Formal Education in the Siem Reap Provincial Office of Education Youth and Sport and to the Department of Non-Formal Education in the Battambang Provincial Office of Education Youth and Sport in 2000. Support from the World TERAKOYA Movement continued to be provided until 2003.

Village volunteer teacher

Source: NFUAJ

Programs were implemented in literacy education, basket making, poultry farming training, and skill trainings including handicrafts (sewing with machines, electrical repairs, sericulture, scarf weaving, mat weaving, woodcarving), and the like, matched to local needs in the provinces.

During the decade from 1994 to 2003, approximately 15,100 people in Siem Reap Province and 17,600 in Battambang Province became literate, and approximately 3,300 people in these provinces received vocational training in handicrafts. When literacy education in Oudong and basic elementary education in Battambang are included, approximately 36,900 people were given opportuni ties to learn.

Since 2003, when support by the NFUAJ ended, the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sport and the Siem Reap Provincial Office of Education Youth and Sport have not been able to secure adequate budgeting (the fiscal base) to continue TERA KOYA activities. The NFUAJ therefore decided to provide continued support.

The NFUAJ took a lesson from experience with the Phase I program and opened an NFUAJ Cambodia Office in Siem Reap Province in 2006. Together with the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sport, this office started up the Angkor TERAKOYA Project.

Source: Socio Economic of Siem Reap 2009

The main aim of the project was to establish TERAKOYAs in nine regions within Siem Reap Province in Cambodia, carry out activities centered on TERAKOYAs in the fields of literacy education, improve income and strengthen communities, and by providing provincial government officials and people in charge of education with training about the running of TERAKOYAs, to offer a chance for education to the people of the province who had thus far not had any opportunities to learn. The project also aimed to support the spread and development of the model CLCs to other parts of the province, and ensure their sustainability.

The purpose of the World TERAKOYA Movement is not by any means to be a TERAKOYA buildings’ construction activity. Depending on the country, there are many places where TERAKOYAs borrow private houses to operate in. As the sites where non-formal education takes place, it is of great importance that TERAKOYA locations receive understanding and participation by villagers, and that they can be made into places that the villagers will operate on their own responsibility, with the understanding that the TERAKOYA are their very own TERAKOYA. Even when the program puts up a building, therefore, much time and effort go into the process that leads up to construction.

A number of regions where literacy is low were selected in cooperation with the Siem Reap Provincial Office of Education Youth and Sport. On-site studies were made to ascertain whether CLC activities would meet the community people’s needs and other such matters.

Explanatory meetings were held to give villagers an introduction to the CLC in concrete terms. The point was made that these would be multi-purpose facilities to be operated by the community people on their own individual responsibility. CLC operation cannot succeed if there is no understanding of the meaning of the CLC among the community people, so this step must be handled with careful attention. Further explanation is given until the villagers are completely satisfied.

As the name implies, a CLCMC is a group of community people involved in operating a CLC. Its members are elected by local residents. The members are usually selected to include people with a variety of backgrounds and influence, such as the village head, civil servants from village offices, teachers, members of the Buddhism Committee and so on. These CLCMC members are given about a year and a half of training that enables them to run the CLC on their own responsibility.

The CLC Visit Program is an extremely effective part of the training.

After visiting classes, the trainees meet with experienced CLCMC members to share their experiences and the specific problems they are facing. For example, a person who is worried about how to gather operating funds might be told to consider loaning out the CLC to other groups and collecting a fee for its use, or making microcredit from the CLC and using the interest income, or some other specific approach to a solution that is based on actual experience. Under some circumstances, an experienced CLC hand will come as a resource person to a vil lage where a new CLC is being formed. The CLCMC members of different villages engage in mutual encouragement, with just a touch of rivalry as motivation, thus serving also as a driving force in the repeated struggle to devise further solutions. Due to the positive popular reception, representatives of the CLCMCs of every vil lage now gather regularly to hold meetings.

Exploring the needs of their villagers and thinking about what kinds of programs to implement at their CLC is also an important duty of the CLCMC. At present, the NFUAJ Cambodia Office and the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sport together with the Governing Boards share their views and opinions with each other while coming to the final decisions about operating programs. These talks constitute a crucial process by which the three parties develop a shared sense of purpose. This information sharing makes it possible to establish and operate CLCs that meet the needs of villagers.

The World TERAKOYA Movement basically asks the community people to take care of land costs (purchase) themselves. This is to heighten the sense of CLC own ership. At Kok Srok Village in Prasat Bakong District, where one was completed in 2007, the village head and many other villagers cooperated in providing the money themselves, holding fundraising campaigns, and the like, and in just eight months they succeeded in raising 600 US dollars for the purchase of a piece of private property some 50 m2 in area. As the community people engage in hard work together, they create their own CLC that, however small, is a repository of their individual thoughts and memories.

Adults in villages that have a CLC commonly work in road construction or other jobs involving heavy physical labor in order to supplement their poor livelihoods. They make the one or two-hour trip by bicycle to their worksite and then the same distance again to return to the village. Then, barely having eaten any evening meal, they attend their night classes in literacy by the dim illumination of generator powered lights. While working at their jobs, they attend classes every day for eight months. This is no easy task.

Another point is that there is a considerable disparity among villages in the percentage of people who pass the final examination. The figures range from 50 % to 90 %. This is a serious issue that also extends to the matter of upgrading qualifications on the teacher's side.

[Example] Literacy Class at the Floating CLC in Chong Kneas (As of Mar. 2009)

Chong Kneas is a village that floats on Tonle Sap Lake. The waterborne CLC there was completely dilapidated after Phase I support was received in 1994, but now it has been newly rebuilt. The opening ceremony was a grand occasion on September 8, 2006 (International Literacy Day), and even H.E. Kol Pheng, then Minister of Education, Youth and Sports, came from Phnom Penh to be among those in attendance.

Various programs are being implemented here to help resolve the problems of poverty. Among those offered at this floating CLC are two income enhancement programs that have even had an influence on other villages.

When volunteers from Chong Kneas Village gathered and made visits to other waterborne villages on Tonle Sap Lake, they found that handicraft products were being made using the water hyacinths that grow wild on the lake. They immedi ately got in touch with affiliated NGOs and held a 14-day class in handicrafts. The handmade bags that women (who learned from that class) make have now become a product so popular that production can hardly keep up. Everyone is glad to have found a source of cash income in this plant that grows wild around them. 80 % of the bags’ sales go to the people who made them, with the other 20 % being applied to the CLC management fund.

This class (an eight-month course) was created at the villagers’ request. Graduates promptly formed an orchestra that has become greatly sought after for local residents’ weddings, traditional ceremonies, and other such events.

The concert fees go 80 % to the individuals and 20 % to the CLC management fund. This successful case later had a great impact on the people in villages where CLCs were subsequently built, such as Prey Kroch Village of Krabey Riel Commune in Puok District and Kok Srok Village of Roluos Commune in Prasat Bakong District, which have developed their own Khmer music classes.

Water hyacinth handicraft class

Source: NFUAJ

In February 2009, a CLC opening ceremony was held in Saen Sok Commune in Kralanh District. This is an area where many of the people travel to the Thai border region to find work during the agricultural off-season from February to April. A report came in that just before the CLC was completed, the members of its Manage ment Committee were talking about staying in the CLC on day-long rotating shifts in order to take care of the desks, chairs, whiteboard, and other learning equipment and materials kept there. They were going to do this even though nobody had requested it. All the people involved in the program who heard about this were greatly impressed to see that the villagers’ sense of ownership had been nurtured to that extent. That was the moment when the goal of “CLC of the villagers, by the villagers, and for the villagers” was realized.

During a meeting with CLCMC members, one member commented that it was extremely difficult to manage their duties on top of their everyday lives. A Japanese supporter then asked why they would serve as members of the CLCMC if it was so difficult, and this was the reply:

“It’s true that things are often difficult, but we find it very fulfilling. Not only that, but the people from Japan work so hard for the sake of our village that it would feel wrong if we didn’t do all we could for the development of our own village.”

Another Governing Board member remarked that

“By operating the CLC, I improve my own skills. (CLCMC members can take part in programs implemented in other villages as well as in classes in their own village CLC. The travel and other actual expenses for this are paid out of TERAKOYA movement support funding.) Not only that, but I have begun getting recognition from many people in my village, and I am being invited to take part in important village meetings.”

By running the CLC, this person is improving his own skills and gaining confidence in himself. This further shows that money is not the only means of enhancing the villagers’ motivation.

In order to have “CLCs that are sustainable by villagers,” it is necessary to estab lish connections with public agencies, other villages, INGOs, NGOs, cooperation groups and individuals, and resource people. Consequently, human resource de velopment for the officials in charge at the Provincial Office of Education Youth and Sport and the members of the CLCMCs also includes ways of finding resources and arranging for cooperation. This is because the classes held in CLCs do not end with literacy but extend to all the variety of health, sanitation, agriculture, aquaculture, animal husbandry, handicrafts, performing arts, and so on.

Cambodian students who have received some higher education and who have direct knowledge of the problems facing Cambodia have also called for assist ance in starting work on improvement where improvement is possible. Therefore a workshop was held on volunteer activity for students with the cooperation of Build Bright University (BBU), a local private university. Perhaps partly as a result, growing interest in the TERAKOYA movement has been shown by university students who are also engaged in their own struggles to earn their tuition expenses. Some of them are serving as CLC teachers, and so the circle of cooperation has grown wider. This gives us a vivid new appreciation of how the World TERAKOYA Movement is being supported by so many people and groups.

The issues for the future are how the knowledge and networks acquired through these acts of cooperation can be used to effect in the field, and how they can be directed toward sustainable CLC operation.

Khmer music class in Kok Srok

Source: NFUAJ

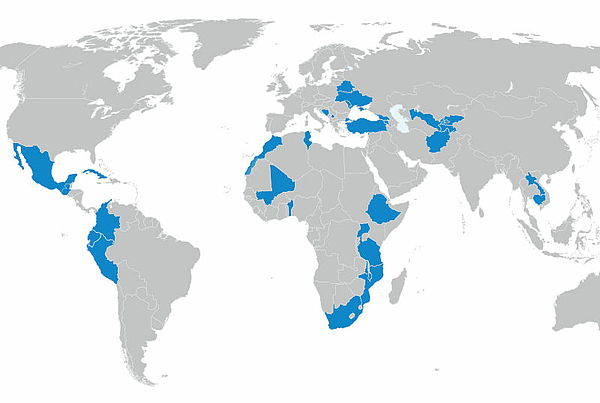

DVV International operates worldwide with more than 200 partners in over 30 countries.

To interactive world map