Janine Eldred of NIACE is also concerned with the impact of the financial crisis and in particular its impact on development assistance. The crisis has set back the fight against hunger and poverty three years. It also led to the fact that the importance of Adult Education is negated by many political actors. Janine Eldred has arguments on why this negative position is wrong.

The House of Commons International Development Committee report of June 2nd 2009, Aid Under Pressure; Support for Development Assistance in a Global Economic Downturn, records that reductions in trade, decreased foreign investment, fluctuations in exchange rates, decreased remittances and changes in development assistance are impacting on the poorest countries. The same report estimates the impact of such financial reductions on human development as;

“An additional 90 million people are expected to be living in extreme poverty by the end of 2010, and the World Health Organisation has warned that child mortality could rise by 400,000 deaths a year.” (P10, 2009)

It also states:

“the eradication of hunger and poverty has been set back by three years.”

(op.cit)

Credit must be given to the UK Government in this context, which has committed to meeting its aid target of 0.7 % of GNP by 2013, and to this end has increased assistance to developing countries in 2009. However, in spite of the government’s Department For International Development White Paper, Eliminating World Poverty; Building our Common Future (July 09) and its commitment to developing a new education strategy, no indication is made of the importance of adult learning. Priority is given to the eradication of poverty without a clear commitment to the importance of educated, skilled and knowledgeable adults who can develop enterprise, employment and effective health and education services.

In such economically extreme times as these, some might argue that prioritising adult learning is likely to be a long way down the agenda. Nevertheless, a reflection on the UKs response to economic challenges and the resulting relative poverty for some groups of people, suggests a contrary view and could help to illuminate why adult learning should be a priority in international development agendas.

In recent decades, during phases of economic downturn, governments have pledged to increase opportunities for education and training. Budgets, attached to skills development and improvement, are made available through work programmes. Information, advice and guidance also increased around the learning opportunities available, along with the support for such things as child-care and travel expenses. Such budget commitments are not confined to governments. For example, the Honda company in the UK declared, at the end of 2008, that the down-time created by the market downturn would be used for training and developing staff, ready for the upturn and new opportunities in trade.

Such responses are in addition to the regular opportunities for developing skills through such massive development as Train to Gain, the employer-driven learning opportunities, including developing literacy and numeracy.

We must assume that the sophisticated machinery of government, which prioritises evidence-based policies, is satisfied that such investments will help to maintain and improve the economic welfare and opportunities of individuals, their families and the nation. Research in this area indicates how those with the lowest levels of skill, particularly in relation to literacy and numeracy, are likely to be the poorest people. Moreover, these adults are also likely to raise families whose children struggle with these essential skills and who find that initial education does not provide the stimulus and satisfaction to encourage them to continue learning. (Parsons, S and Bynner, J (2008) Literacy Changes Lives)

The UK government established its Skills for Life Strategy in 2001, supported by huge funding resources, clear objectives and programmes of action. The work continues today, and indeed, forms a crucial aspect of the support available for people in or out of work, during times of economic difficulty.

Why then, I asked at a conference in Bonn earlier this year on the topic of Financing Adult Learning in International Development, does not only our own government, but also many others in the industrialised world who recognise the importance of adult literacy and numeracy to their own populations, not use the same logic in their international development policies and programmes? What rationale suggests that what is good for human and economic development to combat and prevent poverty and inter-generational deprivation in industrialised nations is not good also for developing nations? One might imagine that the priority would be even higher amongst those people with the longest journeys to take to learning to be effectively economically active.

Some of the arguments against supporting adult learning and literacy in developing countries concern the lack of teachers, the poor quality of provision, a lack of literate environments; in some situations, a history of high drop-out rates, a lack of relevant materials and resources and no clear policies to frame development. Many of these criticisms were features of adult literacy and numeracy development in the UK in the past. They became the reasons for development, not arguments against it.

Under the Skills for Life strategy, teachers had to become qualified to national standards and volunteer teachers were given opportunities to develop, or offered different supporting roles. Curriculum standards were agreed, resources written and produced and all stakeholders were brought to the table. These included employers, trades unions, policy-makers, providers and practitioners. Learners too, increasingly featured as key contributors to policy and practice development. Teaching methods and pedagogies were reviewed, developed and shared, including embedded or integrated approaches, where literacy and numeracy are closely woven into vocational education and training, creative activities and family learning. Such progress can be made where there is the political will.

Some argue that there are subtle, but pervasive forces at play, which stop adult learning being higher on the agenda of developing countries. A recent letter from the Minister for International Development to the Global Campaign for Education (GB) emphasised how partnerships and support for education in developing countries is driven by individual country plans. Where adult learning is not in the national plan, then it is not supported. However, many developing countries feel that, because donor partners indicate that Universal Primary Education is their priority, they will not cite adult learning in their plan, believing it will not be supported. Simply, and understandably, they design the sort of education plans they feel the donor wants to see rather than the plan they would really want in place. They suspend their understanding of the realities of living and working in an African or Asian country in favour of a perceived reality of the potential donor. Governments lose their confidence and capability to drive their own agendas in the face of a fear of reduced donations. The worst aspects of aid dependency emerge in this scenario.

A healthier and more productive approach would be for improved partnerships, where greater equality is exercised. Developing countries should be able to articulate and assert clearly their dreams and ambitions. Partners and donors should examine and reflect on their own in-country policies, especially where these support the Millennium Development Goals, for their effectiveness and potential for translating and sharing in different contexts and countries. For the UK this would mean an analysis of where Adult Education and training contribute to their own policies around employability, workforce development, health agendas, skills improvement, environmental challenges and sustainability as well as to justice, community development and governance, families, early childhood and poverty reduction.

Such analysis would reveal how adult learning does not sit in a silo belonging only to a particular department but intersects, complements and effects policies and programmes across the whole public agenda.

In this environment, developing nations would be better able to negotiate and encouraged to assert where they, in turn, feel adult learning has something to offer in pursuit of their aims and objectives. Partnerships would begin to take on real significance instead of a donor-recipient relationship perpetuating old hegemonies.

Analysis of the Millennium Development Goals, which drive UK international development policies, suggests that most development agendas should have adult learning woven into them. Learning with parents and carers supports effective early childhood health and education; health literacy enhances not only maternal and familial health but also ways of preventing or living with HIV-AIDS. Skills for work in all their complexity are vital for economic development, and more effective where adult literacy and numeracy are included (NRDC, 2006, UK). In the poorest communities, the economic unit is the family unit, whether this is around subsistence farming, produce retail, bicycle mechanics, craft production, local catering or re-cycling initiatives. We know that family learning has much to offer re employability, entrepreneurship, financial education and building skills within the family to be an even more effective economic unit. Building on what works in specific contexts adds value, builds capacity and supports autonomy. These are essential aspects of development anywhere in the world.

By marshalling evidence, experiences and some encouragement, the UK government could lead the way in offering an enlightened, egalitarian approach to development. Investment in initial primary education alone, in any country, is not enough to respond to challenges of now and the next decade. Industrialised countries, working in co-operation and partnership, should recognise the realities of their developing partners in a spirit of global social responsibility.

Adult learning, in all its diverse richness is an imperative in creating the other world we know is possible. We need the political will.

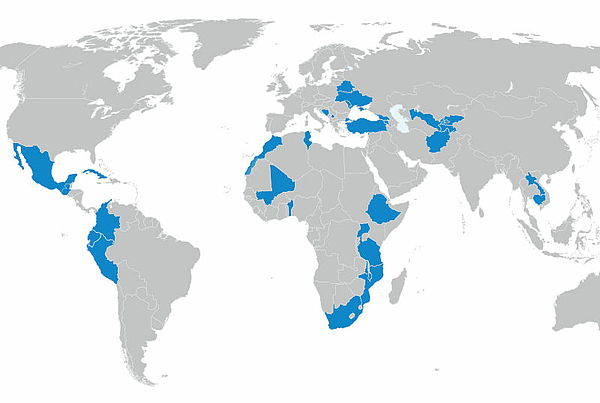

DVV International operates worldwide with more than 200 partners in over 30 countries.

To interactive world map