Gender equality and sustainability in the use of natural resources are two sides of the same coin. Claims of sex-based superiority reflect the same mentality as the hostile approach that humanity has taken toward nature which has led mankind to subjugate and exploit nature to satisfy human needs instead of comprehending that as part of the greater whole, humanity must seek to live in harmony with nature. Proposing a shift in paradigm, the authors discuss the need for new methodologies and approaches in education to achieve the goal of harmonious co-existence.

What does the end of violence against women have to do with achieving sustainability on our planet? Does women’s participation in the decision-making process at all levels have an impact on the protection of natural and patrimonial resources? How is gender equality related to sustainable governance? Although these and many other issues have been the focus of debate for many years, they are still not sufficiently integrated within the daily agendas of people and organizations that work to address socio-environmental concerns.

A few occasions that are commemorated world-wide, e.g. International Women’s Day (8 March) and World Environment Day (5 June), call to mind two other, much larger social movements that arose during the second half of the 20th century: the environmentalist movement and the feminist movement. Both relate directly to sustainability, a subject which in recent years has come to occupy a prominent place on the agenda of the diverse forums and international conferences of the United Nations and other international organizations.

The following text examines a number of issues surrounding cultural change, proposing the implementation of a liberating approach to socio-environmental education based on equality in gender relations and a balance between “masculine” and “feminine”.

What is the purpose of inclusive, permanent, and continuous education if not to promote pedagogical processes that help people feel a part of the surroundings in which they live – processes that encourage people to understand that taking care of the environment also means taking care of themselves as well as others in ways that guarantee the quality of life for themselves and for future generations?

Environment and gender relations form an inextricable nexus that ultimately involves relationships between human beings of all ages, races, colours, ethnic groups, beliefs, nations, and countries, all of which are tied to an understanding of the planet Earth as Pachamama, the Mother Earth of the Quechua and Aymara peoples; Tekohá, the mother house of the Tupí-Guaraní; Gaia, the living being who is home to the entire community of life, including humans. As such, these are issues that must be addressed in every initiative, programme, and project striving to achieve sustainability in human relations, and in the relationship between humans and nature.

As inter-sectoral themes transcending academic subjects, curricula, programmes, and projects, they belong on the agenda of every process of human development and citizenship education, not only in the classroom, but also in every arena in the school of life.

It is no accident that these two generative themes have come to be included in reviews of basic curricula in formal education systems. Nor is it a coincidence that they are a growing focus for universities, NGOs, and social movements in their courses, programmes, and centres, as well as for public and private enterprise, and for institutions which address issues specifically related to the environment or gender equality. These trends can be regarded as signs of gradual acceptance that the environment and gender relations have become a fixed part of agendas for socio-environmental transformation.

Gender-based social relations emerged as a focus of sociological analysis in the 1970s, when a number of feminist scholars in the Subordination of Women Group, a project supported by the British University of Sussex in Brighton, re-examined the theories of Marx and Engels which assert that the production of goods and services forms the sustainable base for society. This group turned a spotlight on the importance of reviewing the existing imbalance in the interrelated processes that synthesize two major aspects of human life: production and reproduction.

In the course of analysis it became evident that the natural and logical order behind human life has been reversed. Goods and services are no longer produced for the sake of reproduction – to nourish and recreate life. Human resources are no longer invested in the service of life. It is rather the case that the reproduction and sustaining of life has become adversely affected by and subordinate to the production of goods.

In this context, with rare exceptions over the last few millennia, the social roles prescribed for men and women have one element in common: men have remained in charge of producing goods and services, with the result that the exercise of power over the economy, government, policy-making and religion have been defined as masculine domains, while women have been relegated to the role of biologically reproducing human life and society while performing all the other domestic functions involved, mainly household chores such as cooking, cleaning, taking care of the children, the elderly, and the sick, and attending to the needs of their husbands. Not being recognized as “work”, these duties have not been ascribed any value.

This perception of the relationship between women and men has had a direct impact on the structures of society. Women have been regarded as inferior to men, including in a legal sense. Under the laws of ancient Rome, women were considered to be the property of men. According to the Napoleonic Code, they were no longer regarded as property, but were considered intrinsically dependent on their fathers and later on their husbands. In the absence of a father or husband, a woman was subordinate to the men of the house who were responsible for maintaining the family reputation: brothers, uncles, or grandfathers. It was not until 1988, with the ratification of the present Constitution, that the principle of equality guaranteeing equal social and human rights for both women and men was explicitly recognized in Brazil.

In recent centuries, the social roles designated to men and women have created new differences, reformulating and deepening social disparity between the sexes. The advent and gradual rise of science in opposition to the wisdom of humanity

– knowledge to a large extent accumulated over the course of history by women

– had the consequence, among others things, of excluding women from scientific

endeavours for many years, preventing them from being officially recognized as scientists, inventors, or artists. The arrival of industrial technology divided the household unit by creating the concepts “worker” and “housewife”, the latter being socially recognized in her identity as “the worker’s wife”. This reinforced the idea that only work performed by men was of value, and that women-specific domestic labour was not.

With the mass inclusion of women in the labour market, their dual role became more apparent. They not only contributed to society as reproducers of the human species, but also as workers involved in the production of goods and services. As such, they had a vested interest in economic, social, and political issues.

This recognition brought about the need to rethink the traditional roles which society assigned to women and men. Masculine roles concentrated almost exclusively on the sphere of production, without any obligation to perform the activities associated with the reproduction of life that women had assumed for thousands of years, and without the consideration and respect that we owe to the cycles of life.

Significant social changes have been taking place against this background. The situation has even influenced the development of new laws to formally define new behaviour patterns. The presence of women in today’s world who exist alongside men as equal human beings with full citizenship rights is progress that cannot be reversed. As observed by Joan Scott (1995), revealing socio-economic, cultural, political, and environmental reality in this manner changes the old paradigm and has a bearing on the construction of knowledge. It influences the use of technology and the practices of social organizations.

When we analyze social and environmental reality from the perspective of new gender relations, we are definitely not looking at something that pertains to women alone, because “the problem is not in the woman” (Viezzer, 1990). The important consideration, when addressing the enormous problems faced by our small planet today, is to identify more points of confluence that can facilitate the construction and perfection of “a different form of being” (Viezzer & Moreira, 1993). This implies finding new ways of organization and coexistence based on equality, harmony, and reciprocity between and among human beings. New relationships between humans and other natural species follow from this as a logical consequence.

But this will not happen on its own, for patriarchal ideology has had a profound influence on our ideas about human nature and our relationship with the universe. Patriarchal worldviews have crystallized into a paradigm that until very recently has never been openly challenged. Its doctrines have enjoyed an acceptance tantamount to “the law of nature”. Fritjof Capra (1993) summarized a number of premises from this old paradigm as follows:

The universe is a mechanical system composed of elementary material building blocks.

The human body is a machine, and medical science is dedicated to the study and treatment of each of its separate components.

Life in a society is a competitive struggle for survival: the law of the strongest prevails.

Material progress is unlimited and can be achieved through economic and technological growth. Cost is no object.

In his book The Turning Point (1983, p. 56), Capra cites Francis Bacon as an advocate of this line of thinking and observes that “since Bacon, the goal of science has been knowledge that can be used to dominate and control nature, and today both science and technology are profoundly antiecological”.

Capra demonstrates how this present attitude relates to woman’s subordination to man. In Bacon’s view, as he explains, nature had to be

“‘hounded in her wanderings’, ‘bound into service’, and made a ‘slave’ She was to be ‘put in constraint’ and the aim of the scientist was to ‘torture nature’s secrets from her.’ Much of this violent imagery seems to have been inspired by the witch trials that were held frequently in Bacon’s time. As attorney general for King James I, Bacon was intimately familiar with such prosecutions, and because nature was commonly seen as female, it is not surprising that he should carry over the metaphors used in the courtroom into his scientific writings. Indeed, his view of nature as a female whose secrets have to be tortured from her with the help of mechanical devices is strongly suggestive of the widespread torture of women in the witch trials of the early seventeenth century.” (ibid.)

We are far removed from the ancient concept of the Earth as a nurturing mother! As Capra puts it, this concept

“was radically transformed in Bacon’s writings, and it disappeared completely as the Scientific Revolution proceeded to replace the organic view of nature with the metaphor of the world as a machine.” (ibid.)

Capra observes that the qualities derived from Baconian premises include selfassertion, competition, expansion, and domination. These are generally considered to be masculine attributes. In a patriarchal society, as Capra points out, not only do men enjoy most of society’s privileges, they also dominate the economy and politics. This is one reason that the shift towards a more balanced system is so difficult for many people, men in particular. This is also the explanation for the natural affinity between ecology and feminism.

The domination/subordination theme in the sphere of production/reproduction, and the connections between this theme and humanity’s treatment of all other beings that are an integral part of nature, have been explored in depth by ecofeminism, a philosophical current of thought that has evolved since the 1970s. Carolyn Marchant, Vandana Shiva, Maria Mies are among the theorists who have refined and expanded on analyses of the old paradigm and patriarchal culture characterized by obsessive male dominance over the female (nature and women) (Di Ciommo, 1999).

The new paradigm recognizes women and men as equals in terms of their social and human rights. It demands respect for biological and psychosomatic differences and the right to cultivate those differences. According to the new paradigm, the biological attributes of men and women are no justification for social inequality, male dominance, and female subordination which prevents women from developing fully as human beings. This is reflected in personal choices, but it also has a direct bearing on the structure of social institutions: family, school, church, as well as political and market institutions.

This view constitutes a complete revision of beliefs and values taught and assimilated as “natural” when, in fact, they are “historical” constructions, and, as such, open to change. These new values and principles already constitute part of the progress that has been made toward a new level of human consciousness. As one of the instruments that integrate the principles of social and economic justice, the Earth Charter, calls for us to “affirm gender equality and equity as prerequisites to sustainable development and ensure universal access to education, health care and economic opportunity.” Under the section entitled Plan of Action, the Treaty on Environmental Education for Societies and Global Responsibility also includes a commitment on the part of educators to “promote gender corresponsability in relation to production, reproduction and the maintenance of life”.

These changes have brought about a need for new studies, new social practices, and new public policies. Significant progress has been made in this respect toward increasing the participation of women in important global decision-making processes, a trend which can be observed, for example, in documents such as Agenda 21 (Chapter 34), Women’s Action Agenda for a Peaceful and Healthy Planet (Rio 1992, analyzed in Johannesburg in 2002), the Declaration and Platform for Action adopted at The Fourth World Conference on Women: Action for Equality, Development and Peace (Peking, 1995), and the United Nations Millennium Goals (UN, 2000). In Brazil, the National Policy Plan for Women (2004 and 2007) specifies the need for equal participation of women and men in various socio-environmental connections.

In challenging the hegemonic paradigm “development at any cost”, the Second United Nations Conference on Environment and Development, held at Rio de Janeiro in 1992 (ECO 92 or Rio 92), was, without doubt, a momentous occasion in that it opened up dialogue on socio-environmental sustainability.

But what does it mean in the sense of the Treaty on Environmental Education to make our societies sustainable in the context of global responsibility? The following definition aptly describes what this entails: A sustainable community is one that:

does not waste financial resources;

does not exhaust natural resources or degrade environmental resources;

values and protects nature;

leverages local resources to satisfy community needs;

values domestic work and recognizes gender needs and the different roles of men and women in the implementation of public policies;

increases livelihood and income-generating opportunities for everyone;

seeks to diversify local economies;

protects the health of its inhabitants, placing emphasis on preventive medicine;

promotes universal access to housing and environmental sanitation services (water supply, sewerage, drainage and vector control, refuse collection and disposal);

guarantees universal access to public transportation;

ensures food security and supply for the population;

guarantees and improves education, training and recreation opportunities;

preserves historical patrimony and local culture; and

guarantees society’s participation in decision-making processes. (Redeh, 2000)

It is difficult to imagine building a community where people live and coexist according to these criteria against a background of domination and subordination between men and women, domestic and external violence, and any other attitude that reflects the lack of an “ethics of care”, starting with human beings.

To ensure all the relevant dimensions of sustainability – ecological, environmental, demographic, cultural, social, institutional, and political – it is absolutely necessary to secure balance and harmony in relations between women and men while at the same time cultivating difference in order to more fully ensure equal human rights.

An implicit assumption in this new paradigm is that balance is necessary between masculine and feminine in all living beings, and that this has direct implications for equitable relations between women and men. Fritjof Capra (1993) summarizes the basic principles that characterize this new paradigm as follows:

Interdependence: the “web of the life” is a network of relations in which the success of the whole depends on the success of each individual, and vice versa;

Energy flow: relations between men and women in search of sustainability are directed in the sense of permanent co-evolution, both of the human species as well as of humanity with other species, in the same way in which solar energy controls the ecological cycles;

Association: women and men, as well as all species, realise a subtle interaction through cooperation and competition which aim at the search for balance;

Diversity: appreciation and respect of the differences between women and men enrich the level of the relations that permeate the web of life.

Co-evolution: men and women, as well as all other species, evolve by means of constant interaction between creation and mutual adaptation.

Accordingly, the worldview that guides our thoughts, behaviours, languages, and our individual as well as our collective practices, is reflected in all our programmes and educational materials (Trajber & Manzochi, 1996). Texts, images, cartoons, and other information included in these materials reflect the way we see – or do not see – the universe, and human beings as part of that universe.

The new paradigm of relationships between human beings and with other living things evokes the need to integrate gender education into socio-environmental education. By introducing the gender perspective when examining similarities and differences between women, and the implications thereof on the relationship between humans and other natural species, it becomes possible to distinguish the natural from the historical.

To respect and cultivate human rights while respecting and cultivating human diversity is the condition sine qua non for making the qualitative leap that will permit us to develop a balance between the feminine and masculine dimensions inherent in all living things.

In this sense, the basic issues dealt with in environmental education are always the same: What vision of the world do we share? What are the beliefs, principles, and values that guide our actions? These questions lead us to other topics that need to be examined, e.g. perceptions, languages, different customs and practices, or participation quotas (especially in decision-making processes). Learning to conduct gender analyses and propose affirmative environmental education initiatives means learning to reframe man/woman relations that were created by society thousands of years ago. These are concepts that still impact the two important spheres of life: production and reproduction. Learning of this nature requires us to use unique approaches and methods, and to adopt new practices in daily life.

It is still common to find educators and environmental educators who are willing “to work with women” in order to guarantee their participation in initiatives geared to “sustainable development”, but who, nevertheless, tend to follow the same patterns established in policies over the past decades. Therefore, it is important to understand how the traditional role of women can be reinforced to serve the intentions of others (family, governments, companies, churches, etc.) without producing any benefits for the women themselves, and in particular without fostering progress toward the achievement of full female citizenship.

Owing to the limitations of space for an article of this nature, we shall concentrate our recommendations on two aspects that deserve special consideration in socio-environmental projects: learning as it relates to elaborating, monitoring, and evaluating projects in line with checklists; and designing proposals in the field of “educommunication”,1 based on the analysis of teaching materials and teaching aids on environmental education.

Dutch government international cooperation agencies have elaborated a checklist as a tool for socio-environmental projects, including those with an educational component. Following is a summary of the main points on this list:

Prepare a breakdown of data according to gender, age, race/ethnic group, socio-economic level, urban or rural sector to identify project participants.

Verify how roles and functions related to the theme of the project are divided up between women and men, and how this division of roles does or does not help to maintain structural relationships of gender domination and subordination rather than relationships based on equality, fairness, and reciprocity.

Identify whether traditional gender roles are changing and what main differences can be observed in the various categories for women (age, marital status, ethnic group, education level, occupation); what is the general situation in all facets of the work assigned to women in the region/place (traditional sector, services, companies), including the occupations which are predominantly female or male and those where there is an increase in numbers of women; what are the main limiting factors for women (in terms of mobility, time, rights of access to technical qualifications and credit); existing or recently lost feminine skills with income-generating potential; who decides on the allocation of resources, costs and benefits within families; what forms of women’s organization (established or nascent) exist at the local level that can be strengthened to promote a greater capacity of organization; what are the attitudes and expectations of women and men toward themes linked to their roles in society and to issues connected with the proposed project.

Verify how women’s participation in the decision-making process can secure the existence of the project; what benefits do women and men derive from it for their lives at home and in their communities; how do men share in the tasks associated with reproduction in ways that allow women to participate in the project without burdening themselves with additional tasks; how are women included in the process of establishing project strategies and priorities; are there follow-up and assessment procedures designed to identify the real impact of the project on women; how is the project related to national policies geared to strengthening the position of women in sustainability-driven initiatives; what is the role of women in elaborating and implementing the project, and how does this role ensure adequate consideration of women’s interests and needs; how does the project foster the quest for equality in everyday life; how can the project gain community and government support to ensure continuity of its initiatives. (Viezzer, Rede Mulher de Educação [Women’s Network for Education], 1993)

Educational materials and teaching aids – including books, texts, magazines, pamphlets, comics, plays, animated cartoons, and manual or electronic games – are important sources of information, and help to change attitudes or to reinforce existing standards.

It is common to find traditional approaches on human beings and how they relate to nature’s other species in educational materials on environmental issues.

Rather than facilitating a shift in paradigm, educational materials around socioenvironmental issues tend to reinforce stereotypes of male/female relationships.

An examination of educational materials and teaching aids offers the following specific recommendations in line with the theme of the present article (Trajber & Manzochi, 1996).

Gender analysis in “educomunication” goes beyond those aspects related exclusively to sexist language or male/female relationships. It seeks to reflect on the factors that shape how socio-environmental issues are dealt with in the mass media, i.e. whether those factors are based on patriarchal premises linked to the established paradigm, or whether they aim to promote equal relationships between human beings and with nature.

To effect any significant change with respect to social relations and the environment, we must begin by using appropriate words and by sending nonverbal messages that reaffirm equality between the sexes and that value sociocultural, sexual, and racial diversity. If we hope to forge new relations between and among people and with the rest of nature, we must necessarily include these parameters in materials that are used to teach environmental education.

The following list of recommendations is intended as a guide to foster analysis and affirmative gender action in the media (Viezzer & Moreira in Trajber & Manzochi, 1992).

Sexist language reflects the patriarchal structure of society. One of the most prominent examples is the use of the word man as a collective word for all human beings, while the word woman only refers to the females of the species. A number of international and national initiatives have contributed significantly toward building awareness about sexist language. UNESCO issued a set of guidelines entitled Redação sem Discriminação (Writing without discrimination) (1996). On 8 March 1996, the National Council for Women’s Rights and the Brazilian Ministry of Education signed a Declaration of Intent in which the Ministry undertook to identify and combat sexism in language used in educational materials, and to make this procedure the norm for all publications geared to primary school pupils. In 2004, as a result of the First National Conference on Public Policies for Women, special emphasis was placed on the subject of “inclusive and nonsexist education” in the Action Plan adopted by the Brazilian presidency’s National Secretariat of Policies for Women. These documents serve as a basis for examining the language we use. Our task now is to learn new forms of good practice. This includes, among other things:

eliminating all expressions containing or conveying a disqualifying or discriminatory message to the effect that women are inferior, absent from public life, and defined and identified in relation to man. There is no justification for maintaining expressions such as “history of man”, “modern man”, and “man who has reached the moon”, which are so common in educational books, and especially in books on natural history. Discriminating words and expressions of this nature must be replaced by more interesting and respectful terms such as “humanity”, “human species”, “men and women”.

Promoting the inclusion in texts and illustrations of images that represent equality, cooperation, and partnership between men and women – adults, young people or children – of different racial and ethnic groups, age groups, religious affiliations, and social positions; and eliminating those containing disqualifying or discriminatory stereotypes.

Depicting situations in which power and leadership are shared by persons of both sexes, and in which both men and women are portrayed in turn as heroic figures, acting in defence of nature and demonstrating a positive relationship with nature.

Issues connected with environmental education are generally complex, but this does not mean that texts about them have to be complicated. To translate ecological vocabulary, expressions, and terminology – obviously without resorting to reductionism – is an obligation of communicators and a demonstration of respect for the readers and learners.

It is an art to make difficult subject matter understandable by using short sentences, simple words, and constructions that are as tangible as possible for the people to whom the material is directed. The use of analogies facilitates understanding, stimulates visualizations, and aids the memory process. The idea, above all, is to engage the attention of the learners, to make an impact, and to bring them new information that will improve their vocabulary and enrich their world. And to generate a climate that leads to mobilization instead of to apathy and inaction. Working with information that generates a negative feeling of powerlessness in the face of environmental problems is part of the old paradigm.

Countless solutions exist. The key is to make them visible. Denunciation is an important vehicle of transformation, but unless it is accompanied by proposals for new ways of dealing with reality, it amounts to empty rhetoric. The emphasis therefore must be on achieving a balance between denunciation and constructive proposals, solutions, and ways to overcome the problems we are facing.

One of the main problems in many educational materials and teaching aids is the fact that they generalize the destructive action of “man”, without specifying that said “man” is white, Western, part of a predatory civilization, and an unquestionabe driving force in the phenomenon of globalisation.

It is always important to understand destruction in the context of its agents. One of the most distinguishing characteristics of patriarchal thought is confrontation, combat, the lack of cooperation, and competition. This either translates into aggression or results in the opposite reaction, namely indifference and apathy. In end effect, corrupt language serves to drain the vast universe of insight open to those who embark on the search for more harmonious relations with their environment.

For instance: Before saying that rivers are dying, why not show how life flourishes in rivers that are still alive, and in rivers that are being rehabilitated? This does not mean that we ought to ignore the reasons behind the death of rivers. On the contrary, the truth of this fact will have greater impact if learners can comprehend the processes and connections behind life in rivers and how it benefits countless species, including the humans. In addition, there is a great deal of experience with river management that is not generally known. Why shouldn’t we call attention to such cases, describe them, and bring them into public focus and in doing so transform the “media” into “channels” of “educommunication”? (Viezzer and Rocha, 1992).

At the same time, there are entire societies and cultures that live in harmony with nature. There is much to learn by way of “demonstration”, especially when we are acquainted with societies and cultures that identify with nature in a positive sense. Essentially, environmental education is an affirmation of life.

As Carlos Rodrigues Brandão points out (1995), it is not about utilitarian values in the sense that doing a better job of preserving the environment will allow us to reap more of its benefits, both now and in the future; nor is it about human pleasure and satisfaction – about not destroying what is beautiful because it is natural. It is because we are part of the chain of life, the flow of life, because we are links in the chain of life that has always existed. That is the point for us.

Being in “the lap of Mother Nature” makes us part of something greater. It places us in communication with nature on a different plane, and makes our relationship with other living species one that is not based on hierarchy. It is a leap from the status of “masters of the world” to “brothers and sisters of the universe”. This, by the way, is what makes all the difference.

For a long time now environmental education has been synonymous with rules and norms of the type “Keep off the grass”, “No smoking”, “No littering”, “Don’t destroy the plants”, “Hunting prohibited”, “Keep our forests green”. Warnings and admonitions of this nature are infinite in number. The extremely normative approach makes it difficult to generate the kind of empathy which is so necessary for environmental learning.

Environmental education must prevail not by imposing obligations to protect life, or by taking a legalist approach to the environment based on concepts of blame and duty. Instead it should underscore the pleasures of being alive. It should kindle a deep sense of fulfilment in living and in sharing life in a system that integrates all living things in the spirit of wisdom and solidarity.

Education, as most of us adults experienced it, was not based on the values and principles of sustainability and the notion of equality between masculine and feminine. And even today it is common to find educators, including socio-environmental educators, who still adhere to the domination/subordination ideology in the relationship between men and women and between humans and nature. It is consequently crucial that we introduce gender analysis and affirmative gender action into education, and that we make socio-environmental communication part of the agenda of learning communities. Issues pertaining to gender and the environment must figure in every topic that concerns us, whether it be the culture of water, sanitation, agriculture, sustainable consumption, biodiversity, selective harvesting, or any other subject.

As affirmed in the Treaty on Environmental Education for Sustainable Societies and Global Responsibility, “we are all learners” regardless of our age, academic background or the circumstances in which our lives develop. This also refers to gender and equality in gender relations. In approaching this “new-old” subject, we must remember that environmental changes are becoming increasingly necessary and urgent. More than anything, they depend on the synergy of interests between human beings. As Paulo Freire stressed during the Day of Environmental Education at the Rio Earth Summit in 1992: “Without man and woman… the green has no colour”. (Viezzer, Ovalles, Trajber, 1995).

Agenda 21 de Ação das Mulheres por um Planeta Saudável e pela Paz [Women’s Action Agenda for a Peaceful and Healthy Planet]. Women’s Environment and Development Organization (WEDO), Network for Human Development (REDEH), 1992.

Agenda 21 de Ação das Mulheres pela Paz e por um Planeta Saudável, Estratégias das Mulheres para a Rio + 10. Relatório da Reunião de Consulta [Women’s Action Agenda for a Peaceful and Healthy Planet, Rio + 10 Conference Report, Network for Human Development (REDEH)], 2003.

Capra, Fritjof. Alfabetização Ecológica [Ecological literacy]. The Elmwood Institute. Brazilian version, Rede Mulher de Educação [Women’s Education Network], 1993.

Capra, Fritjof. The turning point: science, society, and the rising culture. Bantam Books, New York, 1983.

Carta da Terra: Princípios e Valores para um futuro Sustentável [Earth Charter: Values and Principles for a Sustainable Future]. In Portuguese with Commentary by Moema L. Viezzer, Itaipú Binacional, 2004.

Centro de Investigación para la Acción Feminina CIPAF [Centre for Feminist Action and Research]. Guia para el Uso no Sexista del Lenguaje [Guide for the use of non-sexist language]. Ediciones Populares Feministas, CIPAF, Santo Domingo, República Dominicana, 1992.

Corral, Thais. Educação para um Planeta Saudável: Manual para Educadores (as) de jovens e adultos (as) [Education for a sustainable planet: Manual for Youth and Adult Education educators]. REDEH/MEC/FNDE, 1999.

Corral, Thais, ed. Poder Local, eu também quero – Agenda 21 [I, too, want local government

– Agenda 21]. Ediciones REDEH, 1999. Di Ciommo, Regina Célia. Feminismo e Educação Ambiental [Feminism and environmental education]. Editorial Cono Sur, Uberaba, 1999. Trajber, Rachel, and Lucia Helena Manzochi. Avaliando a Educação Ambiental no Brasil [Evaluating environmental education in Brazil]. Materiais Impressos, Editora Gaia, 1996. ONU. Plataforma de Ação Beijing 1995: um instrumento de ação para as mulheres [UN Beijing Platform for Action 1995: An instrument of action for women]. Isis Internacional /

REPEM, Uruguay, 1996. Shiva, Vandana. Monoculturas da Mente: perspectivas da biodiversidade e da biotecnologia

[Monocultures of the mind: perspectives on biodiversity and biotechnology]. Brazilian edition, Editora Global, São Paulo, 2003.

Viezzer, Moema. O problema não está na mulher. [The problem is not in the woman]. Editora Cortez, 1990.

Viezzer, Moema, Omar Ovalles, and Rachel Trajber. Manual Latino-americano de Educação Ambiental [Latin American Manual of Environmental Education]. Editora Global, São Paulo, 1995.

Viezzer, Moema and Tereza Moreira. ABC da Equidade de Gênero na Responsabilidade Socioambiental [ABC of gender equality in environmental responsibility], Itaipú Binacional, Foz de Iguazú, 2006.

Viezzer, Moema, et al. Comunidades de Aprendizagem para a sostenibilidade [Learning communities for sustainability]. Itaipú Binacional, Foz de Iguazú, 2007.

Viezzer, Moema, ed. Trilogia de Educação para a Sostenibilidade [Trilogy of education for sustainability], COPEL, Paraná, 2010.

UNESCO, Redação sem Discriminação [Writing without discrimination], Editora Texto novo, São Paulo, 1996.

1 “Educommunication”, the link between education and communication, refers to the process of awareness building to empower people to defend their right to information and communication, and a means of fostering development (translator’s note).

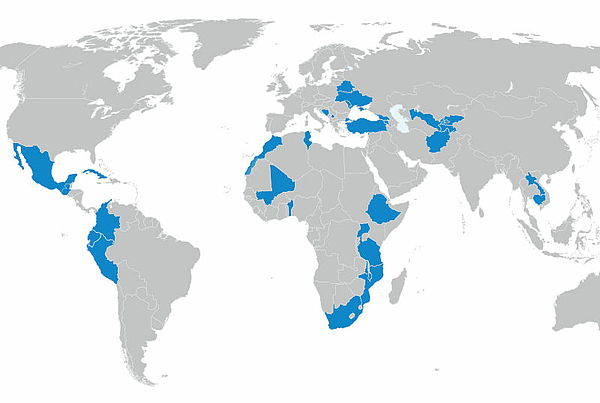

DVV International operates worldwide with more than 200 partners in over 30 countries.

To interactive world map