Samir A. Jarrar

Samir A. Jarrar

Educational Development Group, Lebanon

Abstract – This article paints a picture of the challenges and opportunities facing the Arab Educational systems following the Arab Spring. It calls for cooperative work among the countries in the region to face the ever-growing emergency demands that will be with us post 2015.

The Arab Uprising in the spring of 2011, along with the occupations, conflicts, civil wars and instability in the region makes it necessary to revisit development policies, within a new framework of envisioning a new social contract.

Development needs should be framed within the context of social justice, equity, equality and sustainability. Governments in the region should be transparent and be held accountable. A new Rights approach to development and education, rather than the traditional market-based service provision, should be adopted.

It is easy to make the mistake of stereotyping. We talk about the Arab Spring, or the Middle East, as if it were one and the same uprising, one and the same country. The Arab countries are diverse in their size, population, natural resources, level of development and so on. Nevertheless, many challenges faced in the region are common. Education is one of the main sectors where we need joint efforts to make better use of available resources. This article looks at current challenges and opportunities, calling for cooperative work among the countries to face the ever-growing emergency demands that will be with us post 2015. A new social contract of mutual accountability should be forged by the governments of the region to face the ever-growing disenchantment of the Arab people. We need to break out of the current patterns of unbalanced developments and start to deal with the challenges facing our region (AHDR 2010).

The Arab Uprising in the spring of 2011, along with the occupation, conflicts, civil wars and instability in the region makes it necessary to revisit development policies. What is needed is a new framework, envisioning a new social contract. Development needs to be framed within the context of social justice, equity, equality and sustainability. Governments in the region should be transparent and be held accountable. A new Rights approach (human rights, children’s rights, etc.) to development, rather than the traditional market-based service provision, should be adopted.

The major transformation in the Arab world led by a grass roots momentum has received the attention of the world. Looking at the political scene in the Arab world, we see that in Egypt, masses toppled a secular regime set up in 1952. This is a regime that once promised equity and equality and ended with a ruler that lasted over three de cades. The deposed regime tried to consolidate a new form of government, the “Republic Dom” where “elected” political leaders bequeathed the presidency to their children.

The pinnacle of the mass struggle in Egypt was the toppling of a religious party that was elected to power, and toppled one year after it was installed. This proves that there is more to democracy than just voting.

Similar scenarios can be found in varying degrees in Tunisia, Libya and Yemen. Syria is witnessing civil strife with a regime that is trying to rule by force, denying its people the right of participation. Sudan was divided into two states and instability and conflict are still paramount. Somalia has been ravaged by a civil war that has continued for over two decades. Iraq is still suffering from the aftermath of the forcible removal of a dictator by western forces. I am not sure that the state of Iraq is in any better condition as a result.

Palestine is under an oppressive occupation that has denied its people most of their basic rights, including education and freedom of movement. Lebanon has not yet recovered from its civil war that lasted for over two decades. Jordan, like Lebanon, is another of the limited resources countries that are suffering the burden of hundreds of thousands of Syrian refugees displaced due to the civil war raging in Syria, a conflict that has displaced millions.

The Gulf region is witnessing disenchantment by its people for many reasons. In Kuwait, parliament has been dissolved with new elections taking place nearly on a yearly basis throughout the last decade. Bahrain is facing a struggle by minorities to get their full rights. The rest of the gulf region is facing a series of major issues, including dispute over the rights of women and the role of foreigners.

The presence of migrants in the Gulf, who in some states are twice the number of the indigenous population, is creating social upheavals. Social issues are handled with a Band-Aid approach in the absence of long-term strategies that make use of resources available in the region.

With the political scene as perilous as we have described, national efforts to achieve equitable development have been thwarted. What is happening in the human resources sector of the Arab world?

The end of the twentieth century witnessed metamorphoses in the Arab region sparked by a series of events that included, among other elements:

According to UN statistics, the Arab world population will reach 395 million by 2015, up from 317 million in 2007. Knowing that 60% of the population is under 25, one can imagine what their impact will be on development at large, especially since the region is characterized by extreme disparities and diversity. Challenges include high levels of unemployment, poor job creation and a rapid urbanization of up to 40%. Shortages of water and food are partly due to environmental degradation and pollution.

Four decades of enhancing the capacity of Arab governments to reach the Education for All goals have resulted in some impressive statistics. 88% of the children of primary school age are enrolled in schools. Universal enrollment is spreading in the Arab region with an adjusted enrollment rate of 95% or above. These figures are reported by governments, and published by UN agencies. They are questionable at best. Data collection and statistics have been a problem in the region due, among other reasons, to the political will of governments, and related societal and population distributions by ethnicity, factionalism, and religious beliefs. Lebanon is a country that has not had a census since 1932. Even published census statistics may not always be reliable for some countries.

The educational system in the Arab world has witnessed significant gains in enrollment and gender parity at the primary level. At the secondary level, 69% of the cohort is enrolled, with variances at all levels. The noticeable achievement at the gender level is that girls are outperforming boys in most Arab countries. A reversal in gender gap in mathematics has been witnessed. In many countries girls are going to higher education institutions in greater numbers than boys.

The sad picture is that there are over five million children out of school at the primary level, 61% of them are girls. In spite of the 50% decrease in illiteracy rates in the last decade, we still have over 50 million illiterates in the Arab world.

Growth in access has resulted in a shift from quantitative focus on access to a concern with qualitative aspects of the educational process. Learning outcomes have been deemed less than adequate. The Arab region also witnessed little progress in Early Childcare and Education. It is estimated that 19% of the pre-primary school cohort are enrolled, out of which around 75% are enrolled in private pre-schools, in comparison with 33% of the world average. The question is how this will affect the process of socialization and character-building of our children. Research points to the importance of these early formative years.

The other major issue here is that most Arab countries have not yet included pre-school education as part of their educational ladder or prepared adequate curricula for the cycle. Preparing teachers for the early childhood cycle is a new program in most colleges of education, which are archaic in their teacher-preparation process. The pool of teachers, when available, is limited and the teachers are not well trained. The most serious issue, however, is the availability of proper facilities and financial resources at a time when most ministries of education are suffering from shrinking budgets, especially since 85% of these budgets are spent on salaries.

The good news, however, is that educators and ministries of education in the region are starting to realize the importance of pre-school education and the positive effects on children attending pre-school. Graduates are better prepared to enter the elementary cycle and stay rather than drop out. Pre-school attendance shuts off one of the main channels leading to illiteracy.

Major efforts and funds have been invested by Arab governments in education reforms. Total public expenditure on education in the region exceeded 4.7% of the gross national product (UNDG 2013).

Nevertheless, significant inequalities persist between and within countries of the region. Aggregated averages of educational indices mask inequalities in levels of opportunities available, as well as the attainment level and outcomes. The “mutually reinforcing disadvantages”, such as urban/rural divide, along with income, minority status and conflict and occupation-affected countries are still at play. As for gender issues, it is noteworthy that by 2010 girls accounted for 47% of total enrollment in the primary cycle with the possibility of reaching parity by 2015. However, the crisis and emergency setbacks in the region may reverse this positive trend. In fact, national efforts to improve quality and outreach of the educational system have been hindered by instability, internal strife, civil wars, occupation, protracted conflicts and global economic disruptions as well as the financial crisis. All these factors are key reasons for the reversing achievements in education that we now see. An example of the negative effects of conflict can be clearly seen in the case of Syria. In 2009, 93% of primary school children were attending schools. In 2013, due to the civil war, up to 20% of the school buildings are totally damaged, enrollments and attendance have decreased significantly, especially among the millions of displaced Syrians, internally and externally.

Iraq achieved nearly universal primary education by the late 1990s. After the war, Western sanctions and the increased violence made attendance rates fall to 71%, leaving at least a million children out of school. As for Palestine, where occupation and apartheid treatment by the occupiers prevails, primary enrollments witnessed a decrease, from 92% in 1999 to 87% in 2010. (UNESCO 2012).

Education reforms in the Arab world have not always been accompanied by equity, effectiveness and efficiency. They have not kept pace with socioeconomic and political changes, particularly now with the opportunities provided by and constraints imposed as a result of the political changes we are witnessing all over the region. Many Arab countries lack solid capacity in educational planning and relevant policy frameworks to guide plans and progress that responds to the new learning needs of students at different educational levels. Another major obstacle in the region is that most countries are ill-equipped with data collection and analysis and information management systems to feed into situation analysis and policy development. The potential for transformation has not been fully grasped.

I believe that this is a golden opportunity for the Arab world to take stock of the populous transformation taking place at this juncture in our history, to rework our joint agenda of advancement and development, analogue to the European Union model, to join our resources, manpower and will. With a common language, history, traditions, and all sharing a monotheistic faith, Arabs have an opportunity to tackle their problems jointly with a much higher possibility of success. We have done it before.

When we look at data in the Arab region we face major problems. The region has undergone many attempts at reform and building information management systems in ministries of education. The problem with data collection and analysis remains, with few exceptions.

The validity of data remains the main issue, along with its timely availability to influence policy decisions. Even when we speak of 50 million illiterate Arabs, the aggregate figure hides a lot of valuable information that is needed by decision-makers to produce sound policies based on real information. For example, I am not sure if we even have the data divided by age and gender in allocation of these illiteracy figures.

Our indices of formal education are still far better than those on non-formal education and Adult Education specifically. In fact, this sector of the educational scene has always been problematic, and not very productive. Hundreds of millions of dollars have been spent on different programmes ranging from literacy campaigns to all sorts of empowerment programmes, for women, dropouts, basic vocational skills, etc., with little to show for it.

The major issue is that non-formal education is not integrated into the educational vision of most countries. In most countries of the region the education system is very traditional and closed. It is very hard to move from vocational or technical education programmes to academic ones. The re-entry of dropouts to the main education stream faces major hurdles. It is hard enough to move from one college to another within a university. It is much harder to move from one institution to another in the same country without losing a lot of time and effort.

It is possible to identify several issues arising from present developments. The uprisings in many countries of the region underline needs not appropriately addressed before 2011. We see in particular that:

A new educational paradigm should be envisaged to answer the needs of the Arab world. This paradigm should take into account educational philosophies and development visions on national and regional levels. Based on new brain research and its link to knowledge formation, learning theories and processes, along with the advancement in the field of technology and communications, we can develop a new paradigm that will not necessitate being schooled for fifteen years before completing high school. Steps in the right direction include: seeking learning quality and developing new curricula, renewing pedagogy, raising the social status of teachers and professionalising the teaching cadre. We must also make teachers and trainers accountable by linking all these processes to their promotion and their salaries.

Teachers in the Arab world are suffering from serious problems affecting their performance. Their training is mediocre at best, their social status has deteriorated over time, and their financial rewards are low in comparison with other professions.

The admission standards for colleges or schools of education are among the lowest in higher education. Teacher preparation, faculties and programmes are too traditional in their approach and methods. Little attention is given to in-school internship and there is not much help from supervising teachers. Once teachers are in the classroom, they are faced with large numbers of students, little ancillary materials and nearly no monitoring and support. Teachers are overburdened by assuming too many difficult tasks and responsibilities with very little help or real training.

A shortage of teachers in the region, along with budget cuts, has led ministries of education to recruit novice teachers without pedagogic training. In-service training follows classical out-dated models where talk and chalk is paramount. This must be changed and improved.

The professionalisation and empowerment of teachers was a major decision taken by Arab heads of state in their Khartoum Summit in 2007.

A task force was formed under the auspices of the League of Arab States, and all major Arab Educational centres, supported by UNICEF. A Guiding Framework of Performance Standards for Arab Teachers: policies and programme, was developed in 2009 and ministries of education of the region endorsed it as a step towards professionalising teaching. This includes a move towards quality, certification and licensing and improving work conditions for teachers.

It is strange to see after all these efforts, how one of the major ministries of education in the region was able to license over five hundred thousand teachers in less than a year. With all the efforts to start quality assurance programs and to focus on accountability, such behaviour blocks real development of the teaching force. This is slowing us down and is counter-productive when learning is the centre of the new pedagogic paradigm and not teaching.

In conclusion, I believe that we need to revisit the education paradigm. It has served its purpose and times. It was created over three hundred years ago to serve the needs of the industrial revolution. Attempts at reforming and changing the educational paradigm have only been partly successful at times, serving short term goals. Today few countries of the world can claim that they are happy with their educational system. All failures and shortcomings are attributed to educational systems.

The dawn of the twenty first century, with all the ad-vances and challenges it brought to humanity, will create an ever growing need for education and training. We deserve a new paradigm with a vision and an approach that can meet the challenge of our times.

We need the UN agencies, along with their regional counterparts, to convene a blue ribbon committee like Edgar Faure’s, and Jack Delores’, to revisit our educational paradigm and come up with a New Paradigm that answers the challenges we face, and lead our efforts.

Note

1 This paper is based on a presentation made by the author at the Arab Development Forum: Priorities for the post 2015 Agenda (held in Amman, Jordan, 10–11 April 2013 under the auspices of the United Nations Development Group The World We Want). It summarizes working group 4: Access to and quality of basic services: Education in the MENA region. Data is based on UNESCO and UNICEF regional office reports and presentations (2013).

References

AHDR (2010): Arab Human Development Report Research Paper Series. UNDP Regional bureau of Arab states. Available at http://bit.ly/14f57fo

Carnegie Middle East Center (2012): The Arab World’s Education Report Card. Available at http://ceip.org/yJX7Zs

IEA (2011): International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement. Trends in international mathematics and science study (TIMSS).

League of Arab States (2010): Guiding Frame Work of Performance Standards for Arab Teachers: Policies and Programs. Cairo.

Mirki, B. (2010): Population Levels, Trends and policies in the Arab Region: Challenges and opportunities. Available at http://bit.ly/17jN8v3

UNDG (2013): The Arab Development Forum: Priorities for the Post-2015 Agenda. Working Group 4: Access to and quality of basic services: Education in the MENA Region.

UNDP (2011): Arab Human Development Report. Available at http://bit.ly/arGups

UNESCO (2012): Youth and skills: Putting Education to work. EFA Global Monitoring Report. Available at http://bit.ly/Pz2VO7

UNESCO (2013): Moving the post 2015 Development Agenda.

World Bank (2008): The Road not traveled: education Reform in the Middle East and North Africa. Available at http://bit.ly/b119Rg

Yousif, A. (2009): The state and development of adult learning and education in the Arab States. Hamburg: UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning. Available at http://bit.ly/16MRndW

Dr Samir Ahmad Jarrar is a former president of the Lebanese Association for Educational Studies, and an Editorial Board Member of the Mediterranean Journal of Educational Studies. He is also a member of the Arab League/UNICEF Task Force on Quality Education-Enhancement of Arab Teacher Professional Development and Accreditation. Dr Jarrar is the Chairman of the Board of Trustees for the Arab Resource Collective, Chief Executive Officer for the Educational Development Group. He has been a visiting professor at many universities, such as George Washington University, Georgetown University, and Kuwait University. Dr Jarrar has published books on education including, Education in the Arab World, Arab Education in Transition and Core Skills for Training Teachers in Jordan. In addition to his books, he has contributed chapters and articles to various books and journals.

P.O. BOX 13-5639 Chouran

Beirut

Lebanon

+9611 743090

sajarrar@hotmail.com

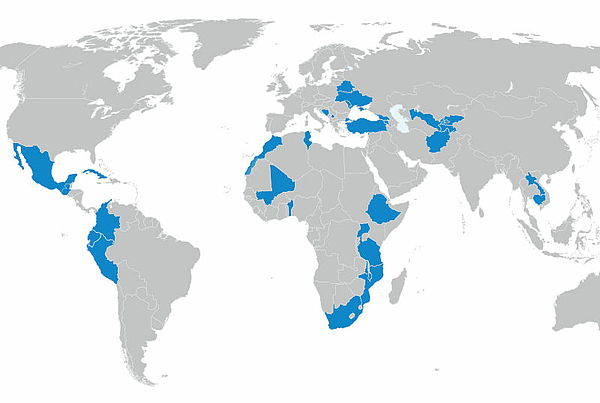

DVV International operates worldwide with more than 200 partners in over 30 countries.

To interactive world map