Camilla Croso

Camilla Croso

Global Campaign for Education, Brazil

Abstract – In this analysis, we will be sharing some reflections on how education and the Education for All (EFA) framework contribute to the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), drawing on the debates currently taking place regarding the post 2015 agenda. From our perspective, the contribution of education and EFA to the MDGs takes place first and foremost given the indivisibility and interdependence of all human rights, whereby the human right to education is a right in itself and one that enables access to other human rights. But the extent to which education and EFA actually contribute towards MDGs depends on the vision and understanding one has on development as well as the sense and purpose attributed to education.

The indivisibility of human rights

Education is a fundamental human right, one that enables access to other human rights. As pointed out by the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights of the United Nations, the right to education, “has been variously classified as an economic right, a social right and a cultural right. It is all of these. It is also, in many ways, a civil right and a political right, since it is central to the full and effective realisation of those rights as well. In this respect, the right to education epitomises the indivisibility and interdependence of all human rights.” (CESCR 1999a).

This core characteristic of the right to education, summing up the indivisibility and interdependence of all human rights, must be increasingly recognised at national, regional and international levels. It impacts the content and direction of policy-making both in education and policies that go beyond. Within the current debate on the post 2015 development and education agendas, recognising the right to education as a social, cultural, economic, civil and political right is of huge importance.

As the fulfilment of the right to education fosters the fulfilment of all other human rights, we should see education placed centre stage in the promotion of the Millennium Development Goals. This is true both for the current goals and for the set of goals being debated for the post 2015 scenario. As Education International rightly puts it, there can be no credible global development framework without the right to education at its core.

The above-mentioned Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights also points out that apart from being a right in and of itself, “as an empowerment right, education is the primary vehicle by which economically and socially marginalised adults and children can lift themselves out of poverty and obtain the means to participate fully in their communities. Education has a vital role in empowering women, safeguarding children from exploitative and hazardous labor and sexual exploitation, promoting human rights and democracy (and) protecting the environment.” (CESCR 1999b).

In this sense, the fulfilment of the right to education responds to and fosters the realisation of all current MDGs: Eradicate extreme poverty and hunger; achieve universal primary education; promote gender equality and empower women; reduce child mortality; improve maternal health; combat HIV/AIDS, malaria and other diseases; ensure environmental sustainability; and develop a global partnership for development. Similarly, it will have a crucial role in promoting the fulfilment of the post 2015 MDG goals, which are still under debate, but which currently point to a set of 12 goals: end poverty; empower girls and women to achieve gender equity; provide quality education and Lifelong Learning; ensure healthy lives; ensure food security and food nutrition; achieve universal access to water and sanitation; secure sustainable energy; create jobs, sustainable livelihoods and equitable growth; manage natural resource assets sustainably; ensure good governance and effective institutions; ensure stable and peaceful societies; and create a global enabling environment and catalyse long-term financing.

Having said this, as important as recognising education as an empowering right of all others, and precisely because of the assumption that understands human rights as indivisible and interdependent, it is important to have in place legal and political frameworks that are enabling all rights, including education. That is to say, education will foster the realisation of all other rights, but the realisation of the right to education will flourish in a context where other human rights are fulfilled. For this reason, at the same time as we must seek to guarantee the realisation of the right to education, we must also struggle for the protection, respect and realisation of all other rights, with sound structural legal and policy frameworks in place to support this. In this sense, countries must adopt policies that structurally impact the social, economic and political scenario towards social and environmental justice and human dignity, such as progressive taxation, redistributive policies, affirmative action that combats historic discrimination, policies that foster social participation in decision-making, policies geared towards the strengthening of public systems, including sound financial budgeting for the realisation of rights.

Debating the means and extent to which education can contribute to the achievement of the Millennium Development Goals not only implies an understanding of the indivisibility and interdependence of all human rights, but also a reflection on what vision of development and of education underpins the MDG as well as the Education for All framework. Before reflecting on the different views in dispute regarding the understanding of Education and its purpose, let us look at an important debate that regional sister organisations have put forward in Latin America and the Caribbean.

In this region, the Education Working Group (GTE for its acronym in Spanish)1, that animated the debate in preparation for the Rio + 20 conference, has challenged the very notion of development and have put forward the concept of environmental and social justice as a horizon more in tune with the principle of human dignity and sociocultural diversity. The vision that inspires this draws from the indigenous people´s paradigm of well living, which compared to the notion of development, is more complex, less linear, allows for contextualised patterns and benchmarks, is inextricably related to the environment and recognises difference and diversity. Well living implies aspects that go way beyond the economic dimension, to include all aspects of human life.

Finally, education will contribute decisively to the realisation of all other rights and of broad development goals as long as it is conceived and implemented as a fundamental human right. To understand education this way you must recognise its purpose broadly, the way it is spelt out in the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights and all other international human rights instruments that followed, with citizens of all ages being right bearers and States being responsible for its fulfilment. In this sense, education must promote the full potential of human beings, respect for all human rights and freedoms, it must value difference and diversity, it needs to overcome all forms of violence and discrimination, it shall promote citizenship and peace as well as harmonic relations with the environment.

Recognising education as a fundamental human right also implies that education be universal, compulsory and free at least at primary and increasingly at all other levels. It implies understanding what the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights established in 1999: that the fulfilment of the right to education requires all its four dimensions be satisfied: its availability, accessibility, acceptability and adaptability. Finally, it implies recognising that the right to education begins at birth and is lifelong, therefore placing at the forefront of debates and decisions the need to put in place educational policies that are geared towards all age groups, from early childhood to adults.

Currently, in the debates that revolve around the post 2015 agenda, there are different conceptions of education in dispute, with most civil society organisations defending education as a fundamental human right, but with important social actors fostering a reductionist vision of education, economist in nature, narrowed to responding to market needs and taking as core indicators measurable learning outcomes, especially around mathematics, reading and writing. In this latter instrumental vision, the focus is on children and to some extent adolescents, but with little or no room for recognising adults as rights bearers. In this sense, civil society has been highlighting the crucial need of attributing increased visibility and importance to adult learning and education, as well as to adult literacy, both in the education and in the development agenda.

Already at the UNESCO World Conference on Adult Education, CONFINTEA VI, civil society from across the world called for increased priority to adult learning and education and to adult literacy. Unfortunately, there has been an overall neglect of these dimensions in the implementation of the current EFA framework and an absence of these issues in the current MDG framework as well as in the post 2015 MDG debates, despite the fact that Adult Education is a core dimension of the human right to education and, as argued at the beginning of this article, has a direct impact in the accomplishment of all human rights. The current neglect in recognising adults as rights bearers and the absence of Adult Education and literacy from the current post 2015 debates is a grave flaw that must be overcome, with civil society, international organisations, Member States and other social actors giving it due priority.

Note

1 That includes the Latin American Campaign for the Right to Education (CLADE), the International Council for Adult Education (ICAE), the Latin American Adult Education Council (CEAAL), Latin American Women’s Network (REPEM), the World Education Forum, the Journey on Environmental Education for Sustainable Societies and Global Responsibility, the Latin American Faculty of Social Sciences (FLACSO, Brazil, www.flacso.org.br) and Education International (EI, www.ei-ie.org).

References

CESCR (1999a): General Comment 11. Available at http://bit.ly/14eWUrB

CESCR (1999b): General Comment 13. Available at http://bit.ly/u3cdyP

Education International (2013): Education in the Post-2015 global Development Framework: Education International’s proposed goal, targets and indicators. Available at http://bit.ly/16Rj9rJ

High-Level Panel of Eminent Persons on the Post-2015 Development Agenda (May 2013): A New Global Partnership: Eradicate poverty and transform economies through sustainable development. The Report of the High Level Panel of Eminent Persons on the Post-2015 Development Agenda. Available at http://bit.ly/1aF1nGJ

Millennium Development Goals (2000): http://www.un.org/millenniumgoals

Camilla Croso, Master in Social Policy and Planningin Developing Countries from the London School of Economics, is general coordinator of the Latin-American Campaign for the Right to Education and President of the Global Campaign for Education. She integrated the Writing Committee of the Dakar Framework for Action during the EFA World Education Forum in 2000 and actively participated in CONFINTEA

VI. She currently integrates various international and regional advisory Boards on the right to education, including the EFA and the Education First Global Initiative Steering Committees.

Campaña Latinoamericana por el Derecho a la Educación

Av. Prof. Alfonso Bovero, 430, conj. 10

Perdizes, São Paulo, 01254-000, Brazil

camcroso@gmail.com

www.campanaderechoeducacion.org

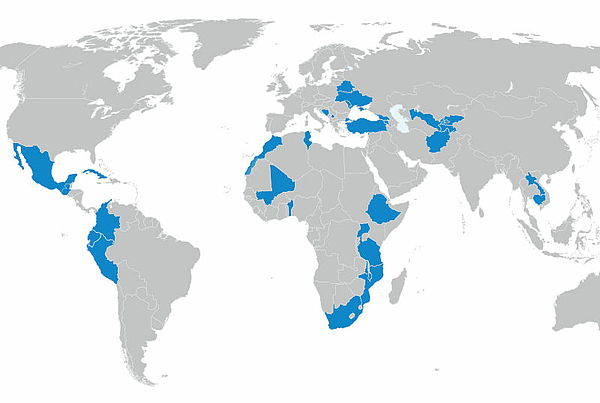

DVV International operates worldwide with more than 200 partners in over 30 countries.

To interactive world map