Jorge Osorio V.

Jorge Osorio V.

University of Valparaiso

Chile

Abstract – In this article the background of the pedagogical and political meaning that adult education has had in Latin America is presented, with a discussion of the problematical contents of the educational policies that have been predominant since the last century and the proposition of some challenges considered key to the development of a new generation of definitions and alternatives.

Since the 80s of the last century adult education (AE) in Latin America has experienced a historical deficit and a significant lag in relation to other educational policies.

The “historic” AE model, developed since the 1960s, was based on the policies of integration, economic modernisation and social mobilisation, promoting itself as a key dimension of community and political participation of the epoch. Under various forms, literacy, adult basic education and training programmes for work were synchronised with participatory educational approaches and criticism of school systems. A certain and relevant vision of the deschooling1 of AE was nurtured by the thoughts of intellectuals like Ivan Illich2 and Paulo Freire3. Freire’s influence manifested itself, also, in the development of a movement of community education with an important political dimension, both in the rural and urban areas. In Freire’s approach, AE was not only a compensatory or remedial education but a “new way to educate the oppressed in order to build a just society.” This same principle led to the popular education movement that developed a major shift – across the continent – in the way we understand AE, associating it with political awareness and coordinating it with social and liberation movements.

The transition of AE from the 1980s to the 90s was difficult and had negative consequences. The so-called consensus of Jomtien4 (1990), which was politically and rhetorically significant, had its interpretation simplified for the implementation of local education policy: a slogan for an education that would meet the basic learning needs of the population was reduced to the development of basic education for children, losing the sense of the Jomtien approach.

The priority in basic education, in the expansion of the coverage of school systems, in improving infrastructure and the use of new educational materials occupied the central position in the political will of governments. AE was shifted to a second level. There was a weakening of the institutional, financial and political economics of AE.

This was expressed in the reduction of national budgets to AE, the lack of leadership from the ministries to promote new projects, the disappearance of specialised divisions in governments and in the migration of technical staff. AE was reduced to compensatory programmes, remedial education and basic literacy.

Economic processes and the implementation of freemarket-driven modernisation policies in the region since the 1990s generated a new cycle of AE oriented on training and on instruction for work. However, this cycle has also had serious structural problems in not adjusting AE to the improvement of technical education, not synchronising AE with the demands of local and regional economies in a diversified way, but especially by privatising the training system, which left AE oriented toward training for work, as a prisoner of the narrow and instrumental offers demanded by companies. The lack of incentives, subsidies and recognition of the needs of the population disregarded all the capacity for development and autonomy of the people who potentially wanted to be trained according to their own decisions and learning expectations. Not even the trade union movement was able to create alternatives.

Another serious issue was the growing pressure of youth on AE education systems. The young school drop-outs saw AE as a way to complete their studies. For them, AE begins to open itself to the name: education for youth and adults; however there is political and institutional confusion about this. There is neither infrastructure nor teachers, nor methodologies to meet this new fact. And we are still waiting to see “case studies” on how some have begun to respond to social and educational challenges of this new reality of an “AE in which youth are the majority”.

A proposition at the preparatory meetings for CONFINTEA 1997 (Hamburg) initiated a process of critique (still in force) of the situation of AE and its mismatch with social, cultural and the demands of the citizenry. This process, led by UNESCO, CREFAL and CEAAL put an emphasis on what the basis should be for a new generation of AE policy. CONFINTEA in Belém (2009) showed how little progress had been made in this regard, despite the strategic recognition of AE as a path to the democratisation of education in the so-called knowledge society.

Without a doubt, between 1997 and 2000 (with strong support from OREALC-UNESCO and CEAAL) a body of approaches was developed to remove AE from its cage and connect it with the educational reforms that had been developing on the continent. In 2000 as well, the first national evaluations were already available – and from international agencies themselves – in relation to the deficits of educational policies; assessments promoted by multilateral agencies such as the World Bank began to consider the issue of quality of learning as the core, as well as the reform of secondary education, working conditions of teachers, the new curriculums and the necessary link of the school system with families and the development of their cultural capital.

Since 2000, our view has been that these tasks must be undertaken from an AE approach that recognises the human right to education throughout life, and that the strategy should be focused on the development of skills needed so people and their communities achieve their full human development. Certainly, all within a framework, still ambiguous, about the role and ways of organising AE school systems and the search for an “institutionalisation” of AE which responds to the new challenges which have been described.

This is not the moment to develop – in this article – the fundamentals of the approach to capabilities in AE, it is enough to point out the conceptual, pedagogical, curricular, technical and the concept of the relationship between education and the “world of life” as well as the “world of the citizenry” that would be imprinted in AE if we propound it; a “critical pedagogy of life” oriented toward issues such as: development in the subjects of their ability to self-manage and recognise their civic power; the ability to create, share and manage “common goods” (natural resources, biodiversity, cultural heritage). In summary, an education oriented to extend the exercise of rights for the citizenry and to ensure access, for the individual and for the community, to the common cultural goods which are generated by science and technology.

Currently there are several definitions circulating that are affecting the development of an AE for the citizenry:

We think the latter approach allows us to conceptualise, in a promising way, an AE focused on the learning needs of individuals, to rethink the dynamics of social demand for AE and design new institutional forms for a public policy of AE. In the same way, this approach is an appropriate backdrop to study what AE means as a complex cultural phenomenon that involves various actors, their cultures, their languages, their gender, their age, their territories, their knowledge, their organisations and their “sensibilities” or life projects.

If the central focus of AE is the learning of the subjects, we can equally raise issues like the demand for the development of AE in the places where participants live and work, the re-connotation of reading and writing in a society, be it a network or a digital space, the redefinition of curriculum according to the territories and participating populations (indigenous people, migrants and displaced persons, people with special needs), among other things which are no less important.

However, adoption of this approach brings with it critical consideration of the relationship of AE with the approach of “training needs” and of “human capital” on the part of “modernising” neoliberal policies of job training and “entrepreneurship” and the elucidation of the capacity of the current economic model to satisfy an educated population through decent jobs. At the same time, it is necessary to design an alternative to the vision of AE as merely for “labour” or a “profession”, giving it new significance as education for human development, where the skills and capabilities of individuals are not only formed to meet the requirements of the economy but mainly to the requirements of buen vivir (the good life), to the participation of the citizenry and the empowerment of the human capacity to act, think, imagine and communicate in today’s society, which demands reflectiveness and the “communalisation” of knowledge as a condition for the development of just societies: an “AE of the community”.

1 / https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Deschooling_Society

2 / https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ivan_Illich

3 / https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paulo_Freire

4 / http://www.unesco.org/new/en/education/themes/leading-the-international-agenda/education-for-all/the-efa-movement/ jomtien-1990/

Picon, Cesar (2016): Hacia centros educacionales renovados de educación de personas jóvenes y adultas en América Latina y el Caribe: ensayo crítico, Revista Educación de Adultos y Procesos Formativos, UPLA. (Towards renewed educational centres for the education of youth and adults in Latin America and the Caribbean: a critical essay). Available at: http:// educaciondeadultosprocesosformativos.cl/index.php/revistas/revista-n-2/ 20-hacia-centros-educacionales-renovados-de-educacion-de-personas jovenes-y-adultas-en-america-latina-y-el-caribe-ensayo-critico

CREFAL (2013): Hacia una Educación de Jóvenes y Adultos Transformadora en América Latina, Pátzcuaro, CREFAL (Towards a transformational youth and adult education in Lati n America). Available at: http:// www.crefal.edu.mx/crefal25/images/publicaciones/libros/EPJA_trans formador.pdf

Jorge Osorio, educator and Chilean historian currently works as a professor at the School of Psychology at the University of Valparaiso (Chile). From 1990–2000 he was Secretary General and President of the Council for Adult Education in Latin America (CEAAL). His work focus is on education for citizenship, lifelong learning policies and emerging practices for psycho-socioeducational professionals in intercultural programmes. His contributions can be found at: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Jorge_Osorio11/contributions

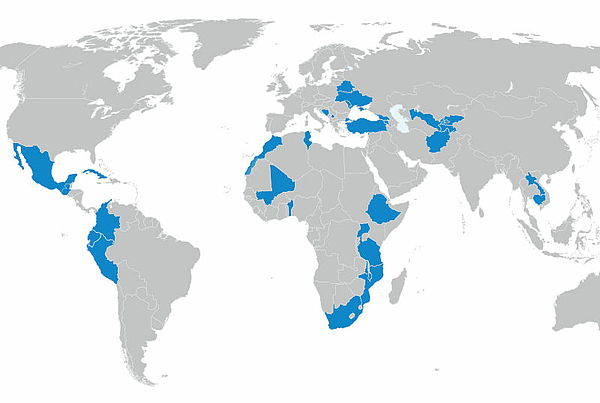

DVV International operates worldwide with more than 200 partners in over 30 countries.

To interactive world map