Selina Banda

Selina Banda

Zambian Open University

Zambia

Daniel L. Mpolomoka

Zambian Open University

Zambia

Abstract – There must be a starting point when we talk about skills and competencies for life and work. It is all very well to list all sorts of cognitive skills we will need in the future. If we cannot even read, those lists are moot. This article looks at the reasons some boys from low-income families do not attend school in certain parts of Zambia, and what can be done about it. The authors draw on their experience as lecturers in adult literacy and research.

Zambia faces many challenges educationally. Not all children of school age are enrolled to learn at the primary education level. Some of these children include boys who are not engaged in any learning activities. Lack of adequate school opportunities and shelter (home environment) are some of the main reasons that are given for not learning. In rural areas, some communities do not have primary schools nearby and children have to walk long distances every day. For some, this becomes an obstacle to learning. In most urban areas, schools are often available nearby. Urban areas have public and private schools that cater for the majority of children. There are government and stakeholders’ community schools that serve children in need, such as orphaned, vulnerable and disadvantaged children. Nongovernmental organisations that offer education to such children include Development Aid from People to People (DAPP) and Family Legacy. In spite of this provision, not all the children enrol and learn in these schools. Among the affected children are some boys who have various reasons for not engaging in learning activities.

Very often it is a question of money. These boys must earn to stay alive. As a result they miss a chance to learn in their childhood and end up as illiterate adults. The missed early childhood education is the crucial stage in human development.

An illiterate population is not only a question of individual misfortunes. Shaw and McKay (1942) contend that, aside from the lack of behavioural regulation, socially disorganised neighbourhoods tend to produce “criminal traditions” that could be passed to successive generations of youths. This system of pro-delinquency attitudes is a clear and present danger for the community. That is exactly why we are so interested in this topic.

Research has been conducted to test for the “reciprocal effects” of social disorganisation (Bursik, 1986) and to test for the potential impact that levels of social disorganisation of given communities may have on neighbouring communities (Heitgerd and Bursik, 1987).

Social organisation and disorganisation influence youth behaviour in many ways. On one hand, the boys of today will hand down behavioural traits they exhibit to future generations; and on the other, they will hand down problems emanating from unity or disunity of family organisations and their (in)stability.

Homelessness is one of the major deterrents that restricts boys’ attainment of primary education. A growing number of boys in the urban areas of Lusaka, the capital and largest city of Zambia, are homeless. They are aged between six and fourteen. The majority are usually found at City Market, Soweto Market, Town Centre Trading area, Kamwala Shopping Centre, Major roads within Lusaka and other trading places in the city. It is common to see boys loitering in the streets and begging for essential commodities from people who pass by. Some of them end up stealing. Without a home to go to, such boys have to find means of fending for themselves. Apparently, the population of these boys keeps on increasing because there are some mothers who are also always on the same streets. These boys end up making such places their home. Since the mothers always take their children with them to the market to go and beg from other people, they are rarely at home. Many of the boys do not attend school because they are always on the streets, trading areas and market places looking for food and other things.

Some of the boys in the rural areas of Katete engage in economic activities to prepare for their future. They do this at the expense of attending school. As early as at the age of six, some start herding cattle. They enter into contracts to work for a period of either three or four years during which they cannot get away to go and attend primary school. They work to earn a herd of cattle at the end of the contract. Some of the boys leave their homes to go and stay with the owners of the cattle while others remain with their parents or guardians while they work. Some of the boys decide to stop herding cattle after finishing the first contract while others choose to go into another one so that they can accumulate two cows. Those that go to herd cattle for one contract have more chances of starting school early at the age of nine or ten than those who go for two contracts. By the time they are through with the second contract, such boys are eleven or twelve years old and have become too old to enrol in grade one. Some of the boys grow up illiterate because of the loss of time in their early childhood, which deterred them from attaining primary education.

Illiteracy handicaps, incapacitates and deprives an individual of the ability to meaningfully integrate into academic and cooperate society. Excluded people do not benefit from education provision. The boys in rural and urban areas have different reputations. While the boys in rural areas work to prepare for their future, those in urban areas live on hand-outs and stealing from other people for immediate consumption. Urban boys do not have a definite future, unlike the ones in rural areas who have homes to go back to after they finish working.

The boys in rural areas prepare for their life early and have stable homes. Parents play an important role in ensuring that they help boys transition into adulthood. For instance, in rural areas parents encourage boys to secure farming portions (farming land). Once a boy comes of age, he is given some farmland to build his household. They work so that they too can build homes for their future families. Coupled with this is the inculcation of traditional knowledge in the boys. Parents teach the boys the “rites of passage”, imparting the necessary traditional knowledge to enable them to function in society. Without doubt, such boys have a chance of learning basic and functional literacy skills in their adulthood.

In contrast, some boys in urban areas come from a background where their homes are non-existent. To a great extent, broken extended family systems have contributed to the boys’ predicament. Research (UNICEF, 1997; Shorter and Onyancha, 1999; Liyungu, 2005) indicates that boys in urban areas desert homes to beg for money on the streets to buy what they want; boys have rebellious attitudes towards parents and guardians. They are concerned with surviving their immediate situation and take things as they come. This makes them unstable and explains their unpredictable behaviour. As a means for survival, they often get involved in immoral activities. They grow up bereft of basic resources for making their own homes let alone the muchneeded knowledge and skills for work and practice.

When children fail to attain primary education, they grow up as illiterates. Boys lacking the basic needs for survival cannot prioritise literacy skills. When they live in places which are not stable and unsuitable for creating homes, they end up not being spotted as people in need of certain facilities such as early childhood and primary education. Without homes or work places, it becomes difficult for education providers to plan for learning programmes to help them. It also becomes hard to reach them with resources meant to alleviate their deplorable situation. Thus, it becomes a double crippling situation. On one hand, when it becomes difficult to identify potential illiterate adults, the likelihood of them growing up without literacy skills is very high. On the other hand, when root causes of illiteracy are not addressed, illiteracy continues to prevail.

When the boys take up roles of herding cattle at the expense of attending early childhood and primary school, they lose out on attaining literacy and skills required in adulthood. If children are allowed to grow up without attending primary school, they end up becoming illiterates. The minute no special programmes for imparting literacy, numeracy and vocational skills are provided to such boys, they remain functionally illiterate.

Once they become adults, they take up roles that have extra demands on them, such as fending for their new families. This is a kind of situation that causes some of these young adults to continue living with their illiteracy. This is a typical situation in which many boys from rural and urban communities find themselves in today in Zambia.

The “working and street boys” require support so that they can develop skills for use in life and occupations they are interested in. They also need literacy, numeracy and occupational skills to develop their cognitive abilities, applicable in enhancing their livelihoods. Literacy and numeracy skills form a basis which can help develop confidence and competence in productive activities they engage in. The skills in this case refer to learned behaviours that draw on a person’s proficiency and capacity to perform certain tasks dictated by the environment one is in. These skills only become viable when they are competently applied in one’s life. Competency therefore denotes “a measurable pattern of knowledge, skills, abilities, behaviours, and other characteristics that an individual needs to perform work roles or occupational functions successfully” (Washington State Human Resource, n.d.).

The boys need context-specific skills that are responsive to their needs. They need literacy and vocational skills to enable them to improve their livelihoods. Olouch (2005) indicates the need to provide occupation-oriented skills necessary for increased economic activity. We are hopeful that this is one way in which those boys who have to spend their childhood herding cattle can be accorded an opportunity to attain literacy and numeracy as well as vocational skills related to economic activities they engage in. This is because literacy correlates with social skills “which brings long-term benefits and has a positive impact on peoples’ personal, family and social lives. It can increase a person’s well-being and self-confidence and combat feelings of social isolation or exclusion” (NALA, 2010:3). World Health Organisation (WHO, 1999) defines life skills as “abilities for adaptive and positive behaviour that enable individuals to deal effectively with the demands and challenges of everyday life”. The skills that enable people to develop competencies for taking up actions for initiating positive change in their lives. Such are the skills required for survival, capacity development and quality of life.

Learning also has to be taken to where the boys are found and allow them to relate it to their daily activities. Doing so will pave the way for experiential learning which offers practical experience conducted in a supportive environment (WHO, 1999). Moreover, we propose that the boys should be provided with their own learning experiences which suit their needs. This can be a way of providing relevant education to the “working and street boys”. This approach corroborates with what WHO (1999) further suggests, that the learning experiences offered should emanate from activities the boys are interested in. For example, the boys in rural areas who engage in herding cattle should be offered related skills in farming. There is also a need to identify what the street boys in urban areas who engage in immoral activities can do to change their lives for the better.

Care must be taken to allow the working and street boys to learn basic skills required for accelerating learning in their areas of interest. This should be done on an understanding of enabling them to construct knowledge and perceive what they want to become in life. The boys should be made to understand and perceive such skill acquisition as a way of transforming their lives and attain an all-encompassing future.

We cannot wait and watch while boys are living without literacy and other skills crucial for their own development. For this reason, there is need to intervene in their lives so these people can adopt lifestyles and patterns of production that will enable them to survive socially and economically. The boys in the rural communities do not participate in education because it does not seem to promise the expected livelihoods. Rogers (2003) agrees that to realise certain benefits, literacy should be contextualised. The type of activities people engage in should give them confidence of sustainability in the future. People need to participate in education activities that encourage them to become involved and committed in creating a society that brings a sustainable future.

There should be an exception for those in urban areas whose livelihood is not stable and clear. They need special measures. The need to impart literacy skills in boys cannot be underestimated. To succeed, a supportive environment is required in which they, too, can acquire skills required for shaping their livelihoods. The aim is to enable the boys to make informed decisions about livelihoods that can sustain them. Though there are concerted efforts being made by both government and other stakeholders (individuals, NGOs, cooperating partners), there is a need to invest more resources. This should be done so that the boys can stop wasting their lives on things which hardly yield tangible fruits.

We cannot afford to continue turning a blind eye to the predicament of these boys, because doing so is detrimental to sustainable development. These same boys are likely to contribute to the cycle of illiteracy and poverty if the situation is not checked and reversed. The vicious cycle of underdevelopment needs to be cut and attention be paid on positive aspects grounded in the inclusion of the boys in basic skills programmes specific to rural and urban settings.

All education activities must begin from the interest and circumstances of the learners. Development-oriented learning should be built on and entrenched in cultural practices of the people to allow for sustainable education to prevail. Learning must be based on the cultural specificity of people’s world view. People’s range of contributions to the development process must be the centre of attention. People’s mode of producing wealth must be the starting point for initiating skills programmes tailored to development of their livelihoods.

There is a need to foster cooperation between skills provision and production activities. The central issue in credibility of skills provided is the appreciation of people’s traditions and lifestyles which serve as the starting point for any learning. The education providers must be fully cognisant of cultural aspects of the people and make them become partners in learning and not mere recipients.

Barnett, R. (1997): Higher Education: A Critical Business. Open University Press, UK.

Bursik, R.J. (1986): Ecological stability and the dynamics of delinquency. In A. J. Reiss and M. Tonry (Eds.), Communities and Crime (pp. 35-66). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Heitgard, J.L. and Bursik, R.J. (1987): Extra community dynamics and the ecology of delinquency. American Journal of Sociology, 92, 775-787.

National Adult Literacy Agency. (2010): Adult literacy service in a changing Landscape. Retri eved from http://www.nala.i

Oluochi, A.P. (2005): Low participation in adult literacy classes: Reasons behind it. Adult Education and Development, 65. Retrieved from http://www.dvv-international.de/adult-education-and-development/editions/aed-652005/literacy/low-participation-in-adult-literacy-classes-reasons-behind-it/

Rogers, A. (2003): Recent Developments in Adult and Non-Formal Education A Status Report on New Thinking & Rethinking on the Different Dimensions of Education and Training. Retrieved from http://www.norrag.org/cn/publications/norrag-news/online-version/a-status-report-on-new-thinking-rethinking-on-the-different-dimensions-of-education-and training/detail/recent-developments-in-adult-and-non-formal-education.html

Shaw, C. R. and McKay, H.D. (1942): Juvenile delinquency and urban areas; A study of rates of delinquents in relation to differential characteristics of local communities in American cities. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Shorter, A. and Onyancha, E. (1999): Street children in Africa: A Nairobi case study. Nairobi: Paulines Publication Africa. Washington State Human Resource. (n.d). Competencies. Retrieved from

WHO (1999): Partners in Life Skills Education: Conclusions from a United Nations Inter Urgency Meeting, Geneva.

UNICEF (1997): The state of the world’s children. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Selina Banda is a lecturer in the Department of Adult Education at Zambian Open University (ZAOU), lecturing in adult literacy, theatre for development and home economics. Before joining ZAOU in 2010, she taught for 19 years in government schools. She holds a PhD in literacy and development. She is currently pursuing another master’s programme in Food Science and Nutrition.

Contact

selina.banda@zaou.ac.zm

Daniel L. Mpolomoka is a lecturer in the school of education at the Zambian Open University (ZAOU), specialising in special and adult education. He served as guidance teacher at a public school before taking up the lectureship; served as course coordinator of the ZAOU Transformative Engagement Network (TEN) Project supported by the Programme of Strategic Cooperation between Irish Aid and Higher Education and Research Institute.

Contact

daniel.mpolomoka@yahoo.com

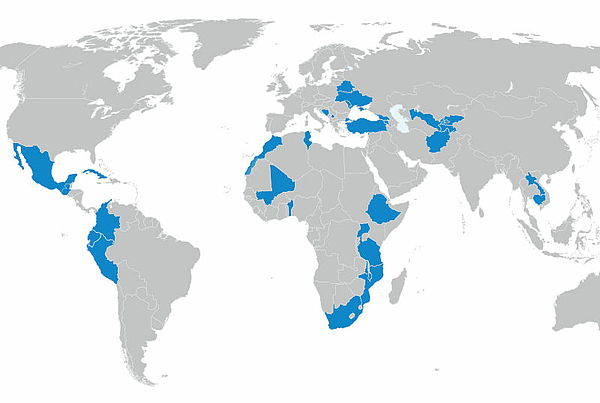

DVV International operates worldwide with more than 200 partners in over 30 countries.

To interactive world map