From left to right:

Helenória de Albuquerque Mello

Federal Institute of Education,

Science and Technology of Paraíba

Brazil

Hilderline Câmara de Oliveira

Potiguar University

Brazil

Abstract – This article tells the story of an inclusive experiment in educating adults in prison, carried out at the Sílvio Porto Penal Reeducation Institute, which is located in the State of Paraiba in Brazil. The experiment was carried out in a classroom with 20 students from the first phase of Youth and Adult Basic Education. During these classes, the students composed a “Cordel” (a popular, inexpensive printed booklet or pamphlet that contains folk novels, poems and songs, produced and sold in street markets and by street vendors in Brazil, especially in the Northeast) talking about education in prison and their life stories.

Everyone is entitled to education. Globally, education is considered to be the best path towards inclusion into society, for children, teenagers, young people and adults. It is also increasingly considered a fundamental human right for personal development. This includes prison inmates.

According to the United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners, “Provision shall be made for the further education of all prisoners capable of profiting thereby, including religious instruction in the countries where this is possible. The education of illiterates and young prisoners shall be compulsory and special attention shall be paid to it by the administration.” (United Nations 1977). The right to education is also guaranteed in Brazilian law (Presidência da República do Brasil 1984).

The experiment which we witnessed took place in the Sílvio Porto prison unit, which was built in 1997 and opened in January 2000. It has a population of 1,328 inmates today, or roughly 25 % of all the prisoners in the State. The prison has 189 cells and 10 blocks. Its capacity is 538 inmates, but it houses a lot more.

At the end of the semester, prisoners present their texts at a closing event in the prison,

© Helenória de Albuquerque Mello

Based on data from the Prisons Directorate, 22.29 % of the prison’s inmates were in formal and non-formal education in 2016: The Literate Brazil Programme (literacy class) had 23 students; the mobility class in the first phase of Youth and Adult Basic Education had 42 students; the second phase of Youth and Adult Basic Education had 22 students, and the High School had 20 students; the Projovem Prison Class had 40 students; the Bible Course – RHEMA had 55 students; the Reading Club had 32 students; the Writing Club had 13 students; the Choir Class had 23 students; the Drama Club had 8 students; the Dance Class (Hip Hop and Contemporary Dance) had 12 students, and the Music Class had six. The prison unit was therefore reaching a total of 147 prisoners in formal education classes and 149 in non-formal education classes during this time.

When questioned about the importance of introducing education practices in the prison, the General Director of the Sílvio Porto prison, and the prison guards, who coordinate the introduction of these practices in the prison unit, said:

“Education plays a very meaningful role in the prison system, [...]. The evolution of the students who study in the institution is noticeable and, when they sign the sentence notification, many of them say that they can now read, that they don’t use their thumbs for signing anymore, that they know what they are signing […]. The institution’s perspective is to broaden the education that is provided by building a classroom and expanding the library so that we can have more books and, consequently, the prisoners will have access to reading, besides the desire to implement the Distance Learning model in order to offer College Degree courses.” (Prison Director)

“In the prison there are spaces which should be filled. The school is one of these spaces, and it must be a platform for inmates’ growth. Day-to-day life, living together with the inmates, shows that it is possible to transform a human being through education. I have seen inmates who didn’t know any Portuguese, who couldn’t read or write, and now they write texts; they know how to express themselves, they are interested in reading, and this is very gratifying. […]. We still have a long way to go, and for me the Cordel that our students prepared is the fuel to keep on this path. The Cordel is living proof that, if you show a man the horizon and encourage him, he will seek growth, change and transformation.” (Prison guard)

Teacher Eliane Aquino – Manager of Prison Education from the State Education Department – illustrates to what degree education can be used for inclusion:

“Education in prison is a tool of social inclusion, if developed from a perspective of improving the human being. In this process, it is important to highlight the role of pedagogical training in the face of the complexity involved in offering education to an audience of young people and adults in a situation in which they are deprived of their liberty. The limits and the obstacles that belong to a historically-established correctional culture, still based on the removal or denial of rights, are hindrances. The initial focus goes back to the training of the actors involved in the implementation process of education in prisons, students, teachers, prison directors, prison guards, through continuous pedagogical planning, based on the pillars of education, so that we could create a common objective and progress together towards reaching it”.

Cover of the Cordel

Excerpts of the Cordel

I went astray through the cities

and confronted the authorities

and lost all my qualities

in prison I was introduced to education

and when I am again part of the nation

I will know how to appreciate my priorities

My name is Fabrício and here I am to talk

about being in school

to make my life as steady as a rock

and show society

that a prisoner can learn as he is taught

for today I go to school and I will never want to stop

We want to thank from our hearts

all those who taught their parts

Director,

Teacher, Coordinator of Arts

the prison guards who were always devoted

to bring us to the classroom

so our minds will be unfolded

We are now coming to the end

as this Cordel has become our friend

we will be here hoping

for the best to come

that education may continue

helping us become one

I didn’t know what education was

my pen was a hoe-and-a-knife clause

now I hold a pen and a notebook in my hand

because education tries our mind to change

it helps new ideas to build

so our lives will be skilled

At school I learned how to read

how to write and how to think

literature was to me introduced

and by many stories I have been seduced

because I have found in education

another way to resocialisation

School is now my place

where I have made reading my fate

so we can get more and more help

and our judge will break our shell

and facing the world this place we will leave

and new stories will be told

Teacher Josefa Rosélia is responsible for the first phase of Youth and Adult Basic Education. According to him:

“The Cordel elaborated by my students is one of these seeds which sprouted and today bears fruit, a reason for all of us, as actors who were involved in this process, to be proud of a collective work in which each member played their part and which culminated brilliantly in 2016 when the actor-students recited their verses at the event that marked the end of our 2016 activities. Education enables new horizons for the inmates; it is a transforming tool, and this transformation is possible. Unfortunately, society doesn’t believe in this possibility; they see inmates as beings incapable of making a positive change, where prison is the final point in their lives, a place where they should remain”.

These statements express a commitment on the part of the Institution to provide education, that is to implement inmates’ right to education as a human right and an element of inclusion in society. Therefore, even after they have left prison, education as a human right is effective when it shows that it is possible to implement the rights of its population.

In 2015, we accompanied a class of 20 students in this prison unit enrolled in the first phase of Youth and Adult Basic Education. 18 of these students crafted a Cordel entitled “In the prison, a Cordel, as in education I excel”, with the guidance of the teacher responsible for the class.

The students were aged from 24 to 45. Among these, 13 students entered prison without having completed the first phase of basic education; three students were taught how to read and write in prison, and only one student had completed the first phase of basic education. As to the time spent studying in prison, ten students had been in the formal education classes for one year, three students had been there for two years and one student had been there for five years. Only one was attending school at the time of arrest. We should mention that eleven students reported having dropped out of their studies because they needed to work after having become parents at an early age. Two students blame the interruption in their studies on their involvement with crime, and two stated that they hadn’t gone to school because they had been homeless.

As for the motivation to study while completing their sentences, the students considered themselves motivated by the possibility of acquiring knowledge, professionalisation, sentence remission, improvement in the way they express themselves and getting away from the prison’s daily life of idleness. These students remained active in the Formal Education classes offered by the Prison Unit.

The interest shown by students from the first phase of Youth and Adult Basic Education in the production of texts was noticed by the teacher, after a poetry morning in the classroom, where she and the students started developing a rhyming activity in a quartet stanza. Following on from this activity, the students started producing texts. Then they came up with the idea of a Cordel, which was developed from each student’s perception of education, transcribing their life stories into rhymes.

The Cordel presents a simple and objective language, but was able to enable these students to take pleasure in reading and writing, retrieving the regional Cordel literature poets, old chanters and the “Repentistas”, the latter being popular poets from Northeast Brazil who improvise on a certain topic and chant spontaneously with rhymes. All of this was done melodically to discuss a range of different topics. Thus, “In the prison, a Cordel, as in education I excel” presents education in rhymes within the prison context from the experiences and perceptions of the students in the first phase of Youth and Adult Basic Education.

The reactions and feelings of the students as they worked on the Cordel were complex, and included happiness, appreciation, freedom and, most important of all: the honour to be presenting the fruits of their endeavours and the dedication from each player involved in the process, which depicts a side of prison life that society rarely sees.

“I thought of myself when I created the Cordel cover, me leaving my cell, pencil and notebook in hand. I looked for inspiration in myself, in the joy I feel in going to school. I feel very happy for having the opportunity to take part in this Cordel, for being acknowledged. I felt more alive, more human”. (Inmate)

“It was the most wonderful thing to me. I never thought I would come up on stage to recite the verses written by each student and which came from our hearts, […] but we give way to studying and I thank the teacher who comes from far away to teach us”. (Inmate)

“It was very good. It brought me knowledge; it was an opportunity to talk a little about who I was; it will bring me good memories from this place. Up to today, I speak there in the prison block. This Cordel gave me the strength to move on”. (Inmate)

“This Cordel was very good for us and for people in society to see that there is regeneration. People think we are hopeless, that we are a hopeless case, that there is no way out, but that is not the case. We can be regenerated, […]. Out there they don’t believe in our abilities, out there they will be amazed when they see this Cordel. Society doesn’t understand that it is the body which is locked up, but the mind can develop and take us to many places. The Cordel is living proof of that”. (Inmate)

“It was very good, it was very different because we didn’t have any means of communication in prison, and this Cordel was a way for us to communicate with the people out there. We are unknown to society, and we are also discriminated against. Few people in Brazil believe that we have the capacity to change”. (Inmate)

“I felt free. I am in prison, but at the same time I am free because I didn’t even know how to sign my name when I first came here. I learned how to read and write here. That is why I took part in the Cordel. […]. When I learned how to write my name, I felt like a silly kid when he’s given candies.

I went from cell to cell telling everyone in the block I could read and write, thank God. People think that those who are here are lost and that they are hopeless. It’s not true. If you are willing, and if you want, there are good people to help you”. (Inmate)

“Taking part in this Cordel encouraged my mind. Education is very important, it shows us a new horizon because life in prison is very hard. When I leave here, I will keep studying. Education will help me leave my thoughts and my previous life behind”. (Inmate)

The inmates’ accounts express an attitude of education discovery as one of the mechanisms for social inclusion and a development as a human being. There is hope that education and reading can bring a new life perspective after prison, and that inclusion is possible. The Cordel was finished, printed and handed out to authorities, family members and guests who attended the event marking the culmination of our 2016 activities, when it was recited by the students.

Thus, the experiment socialised the fruitful results of an action that bore fruit and delivered new knowledge, new reflections and new hopes of life for the inmates. In other words, it showed prison’s good side, which contributes to the prison population’s inclusion/resocialisation process, showing that the prison world can and must invest in developing actions, projects and programmes which enable inmates to gain a new perspective during and after serving their sentence, besides respecting inmates’ rights, respecting sociocultural diversity and the principle of human dignity.

References

Presidência da República do Brasil (1984): Lei de execução Penal. http://bit.ly/1QOAeWs

United Nations (1948): Universal Declaration of Human Rights. http://bit.ly/1O8f0nS

United Nations (1977): Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners. http://bit.ly/1Lh78Q0

Helenória de Albuquerque Mello has a masterʼs degree in Social Work. She is a social assistant of the Federal Institute of Education, Science and Technology of Paraíba, and a researcher of the UNESCO Chair of Youth and Adult Education. She has experience in the area of social work, with emphasis on social assistance policy, penitentiary policy and education policy.

Contact

helen.mello17@gmail.com

Hilderline Câmara de Oliveira has a PhD in Social Sciences and a masterʼs in Social Work. She is a researcher of the UNESCO Chair of Youth and Adult Education, as well as Professor of the Masterʼs Degree in Psychology at Potiguar University and the Facex University Centre. She has experience in higher education and research in criminal policies and human rights.

Contact

hilderlinec@hotmail.com

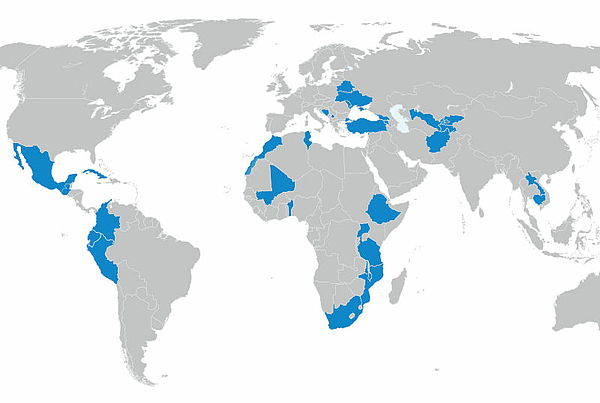

DVV International operates worldwide with more than 200 partners in over 30 countries.

To interactive world map