Werner Mauch

UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning, Germany

Co-authors:

Shermaine Barrett (University of Technology, Jamaica),

Per Paludan Hansen (Danish Adult Education Association, Denmark),

Johanni Larjanko (Bildningsalliansen, Finland),

Ruth Sarrazin (DVV International, Germany) and

Meenu Vadera (Azad Foundation, India)

Abstract – What is professionalisation in adult learning and education? How do we accomplish it? Why is it important? These questions are as old as the field of adult education itself. They are also the topic of this issue of Adult Education and Development (AED). In this introductory article, several members of the AED editorial board paint a joint picture of a complex and ever-relevant question: Who is a good adult educator? For us this is a decisive actor with manifold responsibilities, but first of all he or she is responsible for the quality of teaching/learning processes and their outcomes. To understand this complexity we will look at some of the aspects that we discussed during our 2019 Board meeting: the overall rationale of professionalisation (what?), the profile of the professional adult educator (who?), his or her motivation (why?), and finally the methods for training professional adult educators (how?).

There is a growing recognition that lifelong learning is the philosophy, conceptual framework and organising principle underlying all forms of education. It is based on inclusive, emancipatory, humanistic and democratic values. This concept of learning for empowerment is a central element when it comes to dealing with the rapid changes and challenges that our societies are experiencing. Since we are adults for most of our lives, adult learning and education (ALE) can be seen as the most extended component of lifelong learning. It is necessary for a democratic, just, inclusive and sustainable society. As such, it supports the development of values such as learning to live together, peace and tolerance, and is a critical tool in preventing extremism and promoting active citizenship. Adult learning and education is vital in reaching all of the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and many of their targets.1 Moreover, SDG 4 is about “ensuring inclusive and equitable quality education and promoting lifelong learning opportunities for all”, thus explicitly mentioning lifelong learning as a field of practice, and implicitly understanding adult learners as one of the crucial target groups of education.

The aims of adult education are to transmit knowledge, competences and skills to overcome social exclusion, and to enable all adults, in different target groups and with different needs in our different societies, to take part. To accomplish this, we need responsible agents who organise or “manage” the processes of transmission. We need a “well-qualified workforce in adult education” (Jütte, Lattke 2014: 8). The adult educator is to support the development and “updating” of skills aligned to the current and future needs of our societies. These may be foundational skills such as literacy, active citizenship or vocational skills. But they also include competences to address issues in a wide variety of areas such as health, environment, ICT and many other domains. Consequently, a variety of adult education courses exist, such as basic skills courses, second-chance programmes for school drop-outs, language courses for migrants and refugees, training opportunities for job-seekers, courses on digital skills, professional training for workers, etc. Professional adult educators will however be the ones who not only manage teaching/learning in programmes and courses, but who also see to it that such programmes and courses are in fact delivered by a wide range of providers. Adult educators also assist policy-makers in shaping the overall field of practice. Last but not least, professionalisation should lead to the consolidation of educational practice through reflection on practice, i.e. research, and the maintenance of appropriate institutions to that end.

ALE practice is linked in many places to empowerment processes that are intended to help people overcome situations in which they are placed at a disadvantage. There are often close links between ALE organisations and players in civil society organisations that aim to change the life circumstances of a wide range of target groups. Professionalisation should help adult educators to play this role effectively so that they themselves are conscientious about their role and capacities as change agents, while at the same time being able to make others aware of circumstances and potentials of resistance and change (“conscientisation”). They themselves should also obey principles of non-discrimination.

Professionalisation is therefore about creating conditions for delivering good practice on the basis of appropriate concepts, ideally in the framework of an enabling policy environment. Such policies will look into institutional structures that are needed. Higher education will play a key role when it comes to enabling the conceptual development and research in ALE, while ensuring that the link to teaching/learning practice remains active.

This link will be relevant in both the initial and continuing training of adult educators. Unambiguous criteria are crucial for managing both strands of training. This close link between conceptual development/research and ALE practice, leading to supportive conditions of capacity building, is of key importance to the whole field of professionalisation in ALE.

The question of who the adult educator is cannot be adequately addressed without acknowledging the diverse contexts within which the education of adults occurs.

Inequality exists not merely within and between countries. True, inequalities of income constitute one factor, but those of gender, ethnicity, religion, sexuality and other dimensions make the experience of those inhabiting the multiple axis of inequality more vulnerable than others. Environmental disasters – droughts, floods, tsunamis and earthquakes – exacerbate such inequalities. Conflict that stems from ethnic, racial, religious and other political tensions and economic distress has led to ever-increasing numbers of migrants (rising from 173 million in 2000 to 258 million in 2017 according to the United Nations’ International Migration Report). It is against this heterogeneous context of inequality of opportunities, arising from disasters, conflict and migration to name only a few, that we seek to define and understand who the adult educator is.

The teaching experiences of adults are therefore complex and multifaceted. Teaching takes place in the non-profit, private and public sectors; in formal, non-formal and informal settings. It is virtual or face-to-face; conducted at different levels that are of significance to the learner. The target group is broad, and it includes young adults, older adults, retirees, persons with disabilities, persons with special needs, refugees, workers and community members.

It therefore comes as no surprise that adult educators vary in their practices, in their philosophical perspectives, and in their beliefs and feelings about the purpose pursued in educating adults. Rather than discussing a set of prescriptions regarding who the adult educator is, let us focus on the general notions to which that area broadly applies: The adult educator is someone who works with adults, persons beyond the compulsory school age, for the purpose of learning. We are talking about a relationship in which one aims to facilitate change in the capacity of an adult person or groups of persons. But more than that, an adult educator is someone who, while facilitating learning and change for the learner, is also conscious of his or her own inner learning and growth, and of how that impacts his or her work.

Adult educators therefore go by various names as diverse as the contexts in which they operate. As an adult educator, you may be known as a teacher, trainer, tutor, coach, instructor or development worker, to name but a few.

To understand why someone becomes an adult educator, we need to look at the personal motivation and the context. For some this is a profession like any other. The reason is to have a job, to make a living. There might be other reasons as well, but they are secondary. In places where there are established adult education institutions, this may be more commonplace than elsewhere.

For others, adult education is a calling, something that reaches deep and far. These individuals will care less about salary, career or status. Some are adult educators without perhaps even realising it. In this day and age, many bloggers, YouTubers and social media influencers may very well act as adult educators without being aware of it. There are surely many more reasons, but let us use these as a sample.

Adult educators are rooted in their respective socio-cultural contexts and adult education systems. If we do not understand this, we may run the risk of looking at the issue of professionalisation through our own lenses only. For example, some of us may think that academic training is the best (and possibly only) way to professionalise the field. This point of view may prefer subject knowledge over other (soft) skills. And even if we all agree that subject knowledge is important, it does not carry very far if the teacher lacks personal engagement. There are many adult educators out there who work with particular dedication. You cannot teach this in a classroom; it needs to come from somewhere else.

We try to provide some examples of different adult educators in diverse contexts in this issue of AED through a series of teacher portraits. Many of us will have a vivid recollection of the best teachers we had. This section is also an homage to adult educators all over the world.

The Belém Framework for Action, the outcome document of the Sixth International Conference of Adult Learning and Education (CONFINTEA VI), identifies the professionalisation of adult education as one of the key challenges for the field, and notes: “The lack of professionalisation and training opportunities for educators has had a detrimental impact on the quality of adult learning and education provision (...)” (UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning 2010: 13).

Before delving into how to become a good adult educator, some facts can show a global picture of the professionalisation of adult educators. According to the Third Global Report on Adult Learning and Education (GRALE III), 81% of the 134 respondent countries reported in 2016 that initial, pre-

service education and training programmes were in place for adult educators and facilitators (UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning 2016: 123). GRALE III also shows that fewer than half (46%) of the 134 respondent countries reported that pre-service qualifications were a requirement to teach in ALE programmes. A further 39% reported that pre-service qualifications were required to teach in ALE programmes in some cases, whereas 15% reported that qualifications were not required to teach in ALE programmes.

The CONFINTEA VI Mid-Term Review, however, indicated in 2017 that even if there was growth in in-service and continuing education and training for practitioners, 61% of countries had inadequate capacity (UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning 2017: 7). For example, 56% of countries from the European and North America regions mentioned that a continuing, in-service education and training programme for ALE teachers and educators was available, but that it had inadequate capacity. Only 28% of the respondents describe the training as sufficient. Additionally, studies continue to show that ALE staff suffer from precarious working conditions, with part-time contracts and unpaid hours being relatively common in the sector. Finally, two consultations held in the region in 2016 reported that ALE teachers and educators frequently feel that their voice is not taken into account at the policy level (UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning 2017: 25).

While many countries still rely on non-professional adult educators, others work with volunteers who are trained as adult educators. In general, government entities exert the greatest influence on the training of educators, at both the initial and subsequent in-service stages. The reasons for inadequate training often stem from the way in which the sector is structured and made functional. ALE continues to be viewed as a limited-time project in many countries. In some countries, field functionaries in ALE constitute a relatively stable staff of trainers; in other countries, they work largely on a voluntary basis with nominal financial support; again in others, they are essentially employed by NGOs implementing ALE programmes. It is not unusual in countries with low literacy rates for community members with low educational levels to take over the task of teaching their peers. Considering that a number of NGOs are involved in delivering ALE programmes, prescribing one set of entry qualifications for all programmes and all contexts may not be realistic. This calls for innovative approaches that meet the requirements of quality and equity. As a consequence, the status, conditions of employment and remuneration of adult education staff are invariably below those of personnel in other education sectors (UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning 2017: 18).

As has already been mentioned, adult educators are not always required to have qualifications in order to teach, in part because so few training opportunities are offered.

Let us look at some examples of good practice. The Government of the Republic of Korea established the Lifelong Learning Educator system, a national certification system for professional educators working in the lifelong education sector that aims to guarantee high-quality teaching and learning. Article 24 of the Lifelong Education Act defines a lifelong learning educator is as “a field specialist responsible for the management of the entire lifelong learning process, from programme planning to implementation, analysis, evaluation and teaching.” To be certified as a lifelong learning educator, individuals must obtain a number of academic credits in a related field from a university or graduate school, or they must complete training courses provided by designated institutions. In addition, the Lifelong Education Act prescribes “the placement and employment of lifelong learning educators”, making it mandatory for municipal and provincial institutes for lifelong education, as well as lifelong learning centres in cities, counties and villages, to employ lifelong learning educators. Schools and pre-school facilities that run lifelong learning programmes are also advised to hire lifelong learning educators (Republic of Korea Ministry of Education, Science and Technology) (UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning 2016: 58).

South Africa reported that the government has provided unemployed graduates and young people who have senior secondary school certificates with short-term contracts to teach adults literacy and basic skills. This highlights a shortage of qualified teachers in the field of ALE. The point to stress is that qualifications alone do not guarantee the professionalism of adult educators; however, ensuring professionalism does entail providing initial and continuing training, job security, fair pay, opportunities to grow and recognition for good work in reducing the educational gap in the adult population (UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning 2016: 58).

The quality of ALE courses automatically improves if high-quality training is offered to adult educators, by providing pre-service education and training programmes for educators, by requiring educators to have initial qualifications, and by providing in-service education and training programmes for educators.

The provision of initial training should not only be associated with formal provision of ALE. Adult educators and facilitators should be provided with initial and continuing training, even when the delivery of ALE is non-formal (UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning 2016: 57).

Overall, high quality curricula are needed in order to train adult educators. A curriculum represents a conscious and systematic selection of knowledge, skills and values which shapes the way in which teaching, learning and assessment are organised by addressing questions such as what, when and how people should learn in order to become good adult educators. However, guidelines for curriculum for adult educators are scarce compared to those

for educators in primary and secondary schools.

The CONFINTEA VI Mid-Term Review shows that, in order to ensure the quality of literacy teacher programmes, some countries (e.g. Indonesia and Nepal) have developed a standard curriculum for adult educators that can be adapted to local needs. In other countries, such as New Zealand and Australia, universities and other educational research institutions are engaged in the professional training and development of adult educators.

As an example of recommendable good practice, DVV International and the German Institute for Adult Education (DIE) have developed a basic curriculum framework for adult educators in the shape of their Curriculum globALE, driving towards the professionalisation of adult educators worldwide (DVV International, DIE 2015). It follows the human rights-based approach, taking account of the fact that ALE is one of the prerequisites for the right of self-fulfilment and realisation of one’s full potential. While it outlines the skills required for successful course guidance, it also allows for different framework conditions, contexts and learning expectations. In this issue, we present one example of how the curriculum has been adapted in Laos.

That’s pretty much what we wanted to say in order to introduce this issue. Please read on to learn more and go into depth. We compiled these contributions to support you – as adult educators – in your own learning.

1 / United Nations (2015), for a full overview see https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/development-agenda/

Broek, S.; Buiskool B. (2013): Developing the adult learning sector: Quality in the Adult Learning Sector. Zoetermeer: Panteia.

DVV International, DIE (2015): Curriculum globALE. 2nd edition. https://www.dvv-international.de/en/materials/curriculum-globale/

Jütte, W.; Lattke, S. (2014): International and comparative perspectives

in the field of professionalisation. In: Jütte, W.; Lattke, S. (eds.): Professionalisation of Adult Educators: International and Comparative Perspectives. Frankfurt/M.: Peter Lang.

UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning (2010): Belém Framework for Action: Harnessing the power and potential of adult learning and education for a viable future. https://bit.ly/2LKmc0H

UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning (2016): Third Global Report on Adult Learning and Education (GRALE III): The Impact of Adult Learning and Education on Health and Well-Being; Employment and the Labour Market; and Social, Civic and Community Life. https://bit.ly/30ke1w6

UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning (2017): CONFINTEA VI Mid-Term Review 2017: Progress, challenges, and opportunities: The status of adult learning and education; summary of the regional reports. https://bit.ly/2LOnpE7

United Nations (2015): Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. New York: United Nations. bit.ly/2wNGf3t

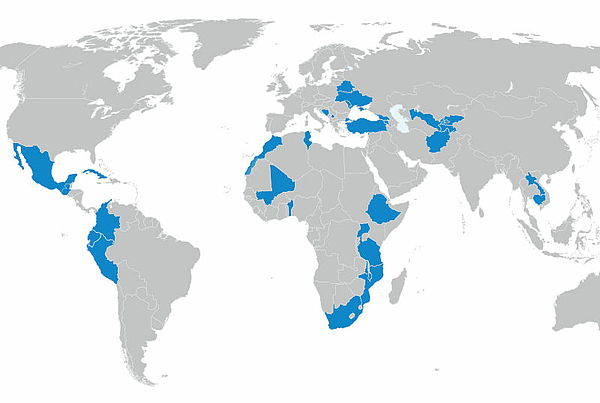

DVV International operates worldwide with more than 200 partners in over 30 countries.

To interactive world map