From left to right:

Khalaf M. Abdellatif

Hiroshima University

Japan

Eisuke Hisai

Hiroshima University

Japan

Abstract – Adult educators contribute to the promotion of an “Egypt with no illiteracy”. There has been renewed interest recently in action research to promote educators’ professional development. While educators’ professional competences have been investigated in detail, more specific research competences have received little attention. Using the mixed-method approach, which includes quantitative and qualitative data collection methods, this article finds that educators attain neither the level of competence claimed in literature, nor attitudes to adopt action research for professional development. Policy-makers and training designers might consider it worthwhile to develop educators’ research competences before applying action research-based training programmes.

Literacy is a universal human right. But illiteracy is blocking development efforts in many countries today, including Egypt. This affects the country on many levels, not least socioeconomically. One sector within education that addresses this issue is adult education. In order to promote literacy, adult educators must be professionally trained and have the right combination of competences. Many scholars have recently argued that competence-based professional development programmes are efficient, and hence the majority of adult educators in Egypt have an adequate level of professional competences. At the same time, globalisation, neoliberalism and other global trends have reshaped the concepts of learning and teaching in the 21st Century. This requires teachers and educators to upgrade their competences. Professional development programmes are now increasingly seeking to integrate knowledge, critical thinking skills, digital literacy, and research-based teaching.

Carrying out action research is a form of professional development for teachers because it empowers them to enhance their practices through reflective teaching, and it helps them to emphasise their skills and develop their professional competences. The concept of “teacher-as-researcher” encourages teachers and educators to be collaborators in improving their work environment, professionalising teaching, and developing policy (Johnson 1993). Teacher research has its roots in action research; it is advancing reform based on actual school experiences, through on-the-ground research.

In this article we use the terms “adult educator” and “teacher” interchangeably to refer to the educator who works mainly in classrooms to contribute to the promotion of literacy in Egypt.

Adult educators need to acquire certain skills or competences in order to do a good job, such as critical thinking, teamwork, decision-making and creativity. These skills, together with educational and teaching competences, are essential for educators to fulfil their roles.

The idea and scope of educational competences are originally related to a major movement in the field of teacher education, namely the “competence-based education” movement, which first began to appear in the United Kingdom and the US in the 1940s. By 1968, this movement had become a trend through the emergence of teacher training programmes. Since then, training programmes based on competences have spread all over the world. It has made teachers and educators knowledgeable with regard to general, professional and specialised competences. In the competence-based programmes, a set of criteria for defining “the efficient educator” are developed on a scientific basis, relying on the principle of sufficiency rather than on knowledge as a frame of reference for training.

Teaching competences and professional competences of the adult educator are not the same. However, they share some characteristics. Teaching competences focus on the role of the adult educator within classrooms, as they are directly related to the teaching profession, professional knowledge, and skills. They include knowledge, skills and directions for the adult educator to succeed in the teaching profession. But these competences are directly related to the teaching process, and do not go beyond the adult educator’s practices within the classroom. Teaching competences depend on the mastery of teaching materials, knowledge of learners’ psychological characteristics, knowledge of teaching and learning methods, the mastery of teaching skills, and the positive trend towards establishing good relations with learners in classrooms.

While professional competences refer to broader and structured scopes of the educator’s professionalism, competences also include the classroom, local community and professional development institutions. Thus, teaching competences are a particular aspect of professional competences. Both teaching and professional competences nonetheless aim to address rapid technological advancements and strengthen the teacher’s performance. Teaching skills are a component of teaching competences; they represent the ability to perform a particular work or activity related to the planning, execution, or evaluation of teaching, and this work is subject to analysis of a range of cognitive, psychomotor and social behaviours. Teaching skills can be evaluated by the following criteria: accuracy, achievement and the ability to adapt to changing teaching positions. The evaluation is done by using structured evaluation or observation methods. As a result, these skills can be improved through training programmes.

Action research is a continuous process of action and reflecting of actions in which practice is inseparable from pedagogical theory. The aim here is to improve educational practices or solve problems through four spiral steps: planning, action, observation and reflective evaluation. The steps are then repeated if the problem has not been solved. Although the literature does not indicate that there is a consensus on who first developed action research, most of the literature refers to Dewey, Collier, Lewin or Corey (McNiff 2014). Kurt Lewin however first coined the term action research in his 1946 paper entitled “Action Research and Minority Problems”.

Action research refers to the link between three elements: action, research and participation, whereby action and research are carried out interchangeably in order to achieve meaningful outcomes. Action research is also used to investigate the dimensions of a specific problem related to the learning environment, so that teachers and educators can reflect on how learners could learn. It is thus defined as a survey conducted by one or several teachers, with the purpose of concluding experiences that improve subsequent decisions, actions and practices (Sagor 2005).

Research competences are important pillars for adult educators, as these competences enable them to undertake research into the degree of their professional development and to improve their practices. The pedagogical research is sought to support educational reform and improve practice. However, the teacher-as-researcher approach is a specific kind of empowerment; it helps bring about more specialised educational reform because it is implemented by teachers

in order to improve their practice.

The literature states that educators-as-researchers need to have the following competences:

We therefore conclude that the research competences for adult educators include an awareness of the varied research concepts associated with adult education and research elements, educational research methods relevant to andragogy, and the role of action research in the professional development of adult educators. It is argued that adult educators are able to design research tools that are suited for use in participatory action research with their colleagues.

There are many programmes for developing professional competences of adult educators in Egypt. Some of them use action research as an approach to develop teachers’ competences, while some other higher education institutions provide action-research training and highlight the potential of action research. For instance, the first annual teachers’ conference dedicated to improving education in the Arab world discussed the potential of action research in formal and informal education. The conference took place in Cairo on 10-12 January 2016, and was organised by the Middle East Institute for Higher Education at the American University in Cairo, in cooperation with the Arab League, the Arab League Educational, Cultural and Scientific Organization (ALESCO), and the UNESCO regional office in Egypt. The event was supported by the Ford Foundation. This is a concrete example where policy-makers in the region are aware of action research, and are considering its benefits. But that is only one level. Are Egyptian adult educators ready for action research? Do they have the research and professional competences needed to drive action research projects in their classrooms?

We chose the governorate of Suez in Egypt as a case study because of its varied environments: industrial, coastal and agricultural. There are also several oil companies, international shipping agencies and many factories in Al-Adabia and Ain Al-Sokhna which make it an attractive governorate for people from all over the country.

The research followed a mixed-method approach. A random sample of 81 educators, 71 women and ten men, were given questionnaires with which to self-assess their competences. In addition, five interviews were held with the management staff of the general authority of adult education in Suez.

The questionnaire was designed to assess the professional competences of adult educators. It was made up of three parts: general competences (seven competences), teaching competences (26 competences) and research com-

petences (17 competences). The educators were asked to self-assess their competences on a scale from 0 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree), with 2 being neutral (neither agree nor disagree). Construct validity was determined, and test-retest reliability was 0.996 (Cronbach’s alpha), which represents excellent reliability and implies that the measure was consistent overall.

The analysis of the results revealed adult educators’ overall level of competence to be 52.3 %. In other words, 52.3 % of the answers were above the neutral level. The general, teaching and research competences were not equally high, and the study showed that the teachers have significant shortcomings with regard to some of the competences. Table 1 gives an overview of the results.

The analysis of general competences, which are essential for any teacher or educator, shows that all the educators examined scored a high level of these competences (80.2% of the answers being above the neutral level). This indicates that the preparation and in-service training of adult educators in Egypt promote their general competences effectively. The top three general competences were: “Understand the theories of adult education”, “Explain the function of adult education” and “Explain the link between adult education and achieving development”. Table 2 provides an overview of all the competences and the results.

Educators showed an adequate level of professional competences, but it is below the neutral level in 56% of the answers, revealing that training programmes are needed that develop these competences effectively. According to the self assessment, the educators scored high in professional competences such as “Plan for teaching adults effectively”, “Manage the teaching situation to achieve learning objectives effectively” or “Help adult learners enhance their achievement levels”. They scored lowest in the competences “Teach adult learners to develop their thinking skills”, “Teach adult learners how to learn” and “Address learners’ diversity and multiculturalism” (see Table 2).

The level of research competences was significantly below the adequate level. Only six out of 17 competences were above the neutral level according to the self- assessment (see Table 2), among them: “Write research reports”, “Show sufficient ICT skills” and “Understand the concepts related to researching in adult education”. The test subjects showed inadequate levels in 11 research competences. Among the weakest were: “Understand qualitative and quantitative research methods”, “Understand the role of action research in the professional development of adult educators” and “Do participatory action research with colleagues”.

The interviews with the management staff of the general authority of adult education in Suez confirmed the results of the questionnaire. The director of the training unit said: “From my experience, I think that adult educators are not good in professional competences, they need more: more training, more action and more work”.

When she was asked about the research competences, she explained: “I am not surprised. They are doing their best, but we do not offer them the right track. I think that adult educators should be made familiar with action research first, maybe through booklets, or one-day training to introduce the concept and its importance”.

All the interviewees confirmed that the adult educators have no problem with general competences, but that they seem to have problems with some professional competences, and that they need to develop their research competences first before adopting action research to enhance their practices.

The study revealed that adult educators in Suez, Egypt, satisfy neither the level of competence claimed in the literature (regarding research competences in particular), nor attitudes to adopt action research for professional development. We think that the time to introduce action research to educators is yet to come. Policy-makers and training designers might consider developing educators’ professional competences and research competences, respectively.

Johnson, B. (1993): Teacher-As-Researcher. https://bit.ly/2Xfpqex

McNiff, J. (2014): Writing and Doing Action Research. London: SAGE Publications.

Sagor, R. (2005): The Action Research Guidebook: A Four-Step Process for Educators and School Teams. London: SAGE Publications.

Khalaf Mohamed Abdellatif, M. Ed., Assistant Lecturer at Cairo University in Egypt. He studies social education at Hiroshima University in Japan. His professional career as a researcher has focused on issues related to action research, adult education, lifelong learning, and community-based learning.

Contact

khalaf.mohamed@cu.edu.eg

Eisuke Hisai, Ph.D., Associate Professor at Hiroshima University in Japan. He is studying Japanese history of adult and non-formal education, especially on the history of the life-improvement movement in urban areas. He is also involved in various education programmes for municipal staff of adult and non-formal education.

Contact

hisai@hiroshima-u.ac.jp

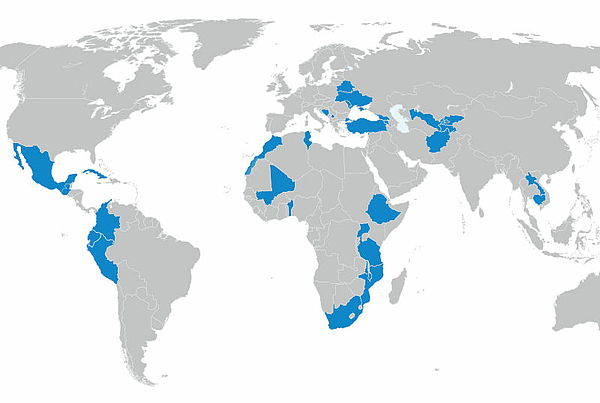

DVV International operates worldwide with more than 200 partners in over 30 countries.

To interactive world map