Interview by Sturla Bjerkaker, adult educator and member of the International Adult and Continuing Education Hall of Fame

© Maria Zaitzewsky Rundgren

Gösta Vestlund (105) is a former “folk high school” teacher, principal and inspector from Sweden. In his unusually long lifespan and career, he has been particularly occupied with learning for democracy. He spent many years working for literacy and folk high school movements in Africa. His perspective on the impact of adult education is quite unmistakeable: Without adult and lifelong learning and education, we would not have the Nordic welfare societies as we see them today, and we would not have well-developed democracies, either in Europe or in other parts of the world.

We are in a nice suburban area half an hour east of the Swedish capital Stockholm, in a semi-detached red-brick house built back in 1961. The bleak sun rising this late February morning shines in through the large windows, revealing a nice panorama of a snow-filled garden. From the television set, the winter Olympic Games from South Korea are flickering through the living room. Nordic disciplines, Nordic winners.

Calm, sitting on his sofa, Gösta Vestlund is the grand old man of Nordic popular enlightenment and liberal adult learning and education. It is called “folkbildning” in Swedish, and is in the same vein as the Danish synonym “folkeoplysning”. It is quite difficult to translate into other languages. This seems to me to be due not only due to the term but also to the concept, as “folkbildning” is hardly recognised anywhere outside Sweden.

“Not quite true”, argues Gösta Vestlund, “my experience from Tanzania for instance tells me that ‘folkbildning’ is possible in other cultures too.”

More about this later.

Gösta Vestlund has been well known in Sweden and in the Nordic countries for many, many years. Turning 105 this year, he was born back in 1913. This means that he has lived through not one, but two World Wars in Europe, the First and the Second.

He lives alone, and does his own housekeeping. His only problem (!) is that he cannot see to read very well any more. He has special equipment which makes the letters 16 times bigger, allowing him to read things like international reports on educational progress, or on the lack of progress. His memory is excellent, and his perspective of the future is even more impressive. Because, as he says: “As long as you’re alive, you have a mission!”

“I went on my first visit to Africa and Tanzania back in 1965”, Gösta Vestlund remembers. “We were ten folk high school teachers from Sweden about to start literacy study circles in different areas of the country. It was a literacy campaign financed by SIDA (the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency) and the ABF (Workers Educational Association), which was back then and still is the largest study association in Sweden. We cooperated with the Institute of Adult Education in Dar es Salaam and the Cooperative Institute in Moshi.”

“Swedish Prime Ministers Tage Erlander and later Olof Palme had contacts with Julius Nyerere, the famous Prime Minister of Tanzania, through SIDA. A Tanzanian delegation came to Sweden in 1971. What they found was a system for educating adults which, they said, was needed in Tanzania as well. ‘We need time before the children are educated’, they continued, ‘so let’s start with the adults.’”

“Yes”, Gösta continues. “I went there again for negotiations in 1974. We discussed how to organise adult education and how to implement the study circle methods. We also presented the Scandinavian folk high school model, and we proposed to start a few such schools to find out if it fitted into the Tanzanian learning culture.

‘Only a few!’, our Tanzanian friends replied, ‘we have 14 million people to educate, so we need folk high schools in every one of our 86 districts!’

Folk High Schools were established, and today 55 such schools exist. They are called Folk Development Colleges (FDCs).”

At 105, Gösta still reads everyday to follow recent developments in adult education. His only problem is to see the small type, © Håkan Elofsson

“As far as I know”, Gösta replies, and hands over a concept note he recently received from the Ministry of Education in Tanzania. It is about The Role of Folk Development Colleges in Reaching Vulnerable and out of School Children/Youth. The note refers to the start in 1975, and relates that more than 30,000 students were attending FDC courses as late as in 2009: “The objective of the training is to provide young people and adults with knowledge and skills that would enable them to be self-employed and self-reliant […]. The FDCs will be One Stop Centres for young people who missed opportunities to proceed in formal education”, the Ministry note concludes.

“Yes, I find it very satisfying, after working for these schools all those years ago.”

He points out that the foundation for the FDCs in Tanzania can be traced back to the 1920s. At that time, the United Kingdom established schools for farmers in large numbers of regions to teach them how to grow crops. These schools did not function well, but when farming was combined with society and local development, as well as with teacher training activities, it started to work. This is almost the same as Grundtvig and Kold did in Denmark 100 years earlier, when they invented the Scandinavian Folk High School Movement.

“What they didn’t have in Denmark”, Gösta adds, “was the opportunity to sit under the mango trees and discuss life…”

Having been widowed, he moved to Dar es Salaam in 1976 with his second wife, and had to learn Swahili. They attended a Swahili study circle in Sweden, and then a Swahili course run by SIDA. He was already 62 at that time, and learning a new language did not come easy. The family stayed in Africa for two years, after which he went back to his ordinary position as Folk High School Inspector at the Ministry of Education in Stockholm, a position he held for more than 20 years all in all, after working as teacher at several folk high schools and as the principal for one in Sweden. During his long lifespan, he also initiated folk high school teacher training at the University of Linköping, where teachers and principals from Tanzania also attended shorter courses. Tanzania is still an important country for Swedish development cooperation, and for adult educators in study associations and folk high schools in Sweden. Eva Önnesjö, who for many years was responsible for international affairs in the Temperance Movement’s study association (NBV), says that a special NGO, “the Karibu Association” is still active with members in both countries, and that around 20 of the FDCs in Tanzania are working together with schools in Sweden.

One of the main tasks which has occupied the mind of Gösta Vestlund during his 105 years is promoting democracy. For him, democracy is much more than free elections, it is a way of being, it is a lifestyle. He agrees that free elections are essential in any country and culture, but argues that the ability to read and write is a foundation and a precondition for democracy. That is why he looks back at his work in Tanzania, Kenya and Ethiopia as work for democracy.

“How do we nurture our democracy”, Gösta asked in his book from 1980

Every year, the Folk High School Tollare outside Stockholm organises a seminar named after Gösta, the Vestlund Seminars. The headline for these seminars is “Democratise Democracy”. “We must keep the dialogue on democracy alive at all times”, argues Gösta Vestlund.

“I have just read the latest World Values Survey Report, and I think I can recognise a change amongst groups, for instance in developing countries. They are moving from being oppressed to being more empowered people. This is a cultural change that we can see in many places, and it is promising. There is a growing number of people in many countries saying that ‘we will not be oppressed but empowered and participating’.

It is also promising to see that young people in Sweden today are increasingly keen to discuss questions and learn about how society functions and in which direction it is moving. The core of democracy is acceptance and insight into all human beings’ equal values and rights. Literacy is of course essential in this context, and let us not forget that this applies in equal measure to environmental issues such as climate change. All this must be seen in a democratic context.”

Our grand old man of “folkbildning” does not know why his health is so good, it goes against all sense … But it is good. His brain is clear. He just doesn’t see so well any more, but he can listen to books and can take part in the human dialogues he finds so important. To be “bildad” (formed) – he says – is to not humiliate others.

“Oh, it is so much, but I must start with my grandmother. Born in the middle of the 19th century, she knew what it was like to be poor. It was a period of starvation in the Swedish countryside at the end of the 1860s. It was essential for her to take care of everything that nature could give and to grow crops wherever it was possible. She also taught me to behave and that I should be on time and do my work conscientiously. She expressed sanity and sensitivity, and she gave me the confidence to express my views, even if we were poor. Everybody should be valued equally.

Another important event which shaped me took place at the beginning of the 1930s, “only” 85 years ago … Three young men who had escaped from Hitler’s Germany knocked on our door. They told us about the growing Nazi regime and what was about to happen in Germany. This opened my eyes to the world outside my local community in the middle of Sweden, and must be one of he reasons for my work abroad and for my views on democracy.”

“The ability and the opportunity to stay in contact and to open a dialogue with others must be the core of popular enlightenment, formation, bildning and therefore of democracy”, says our 105 year-old interviewee, who is still engaged. In 2016 he became inducted as a member of the International Adult and Continuing Education Hall of Fame at the University of Oklahoma, USA.

“A great honour for me”, he said.

An honour for the Hall of Fame as well.

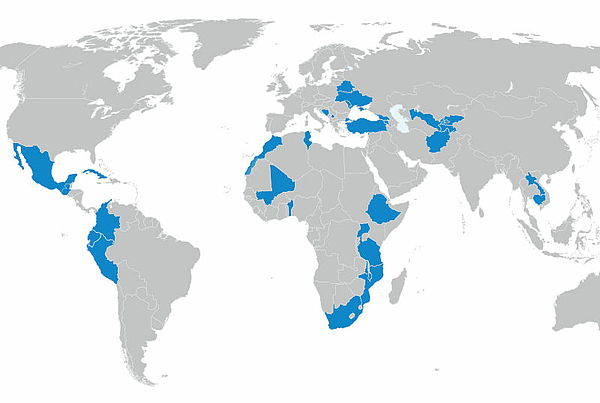

DVV International operates worldwide with more than 200 partners in over 30 countries.

To interactive world map