Carmen Campero Cuenca

Carmen Campero Cuenca

Universidad Pedagógica Nacional

Mexico

Abstract – Adult education is a broad, complex field intertwined with multiple social and educational realities. This article points to a couple of potential key roles for adult education for individuals, their families and communities in Latin America. Some reasons for the limited impact that adult education currently has in the region are also presented.

Youth and adult education is a human right and the gateway to the exercise of other rights. The answers to crucial problems in today’s world, expressed in a global and interconnected way in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), are integrally linked to quality education and lifelong learning for the entire population. Providing youth and adult education are the key to guaranteeing individual and community development and building more just societies (GIPE 2018).

Youth and adult education is relevant in various aspects of individual and community life such as: health and well-being, employment and the labour market (including sustainable livelihoods), justice and democracy, social, civic and community affairs, art and culture, new technologies and social networks.

Despite its importance and potential, youth and adult education is secondary to the agendas of education for children and young people, a condition that can be perceived at different levels and in different situations. For example, youth and adult education is not explicitly mentioned in SDG 4 and its global indicators. Funding organisations also do not consider its role. This lack of priority is reflected in most national budgets, where youth and adult education budget allocations are scarce. The limited or non-existent professionalisation of educators, as well as the compensatory approaches that prevail in many programmes, with little relevance for the groups to which they are directed, are two more expressions of the insufficient importance given to this educational field (Campero 2017). All of the above is in stark contrast to the potential demand and will affect what impact can be achieved.

Educators of young people and adults observe certain changes in the people who participate in socio-educational processes that occur in their daily life or in the medium or long term. The changes can take place in their families and/or environments. In larger projects, it is possible to assess these changes at the different levels of intervention, whether national, regional or local. This is how we can confirm that adult education produces a manifold impact1 that can be appreciated and is important to demonstrate, recognising that it is the result of complex causal relationships. Some impacts can be anticipated and others are unexpected. (Gómez and Sainz 2008 and Bhola 2000).

Experiences that have an impact are often referred to as good practices, or as relevant or successful practices. In most of the cases2 at which we will now look, civil society has played a central role, as have local organisations and institutions of various kinds. Together they reflect the importance and potential of youth and adult education:

The wide range of projects and programmes mentioned in the previous section shows the vastness of this field of education. By analysing them, we can identify characteristics common to several of them, some of them present in a smaller number of programmes, and some more specific.

Some common characteristics of the projects and programmes are features …

Another common feature is that in spite of the strong commitment of the educators and other advocates who develop these projects, they are carried out in precarious conditions, with few resources of any kind, so that their scope and impact is often limited.

These project and programme features support policy proposals that have been strongly expressed by Latin American civil society over the past five years, with a view to defining the SDGs and the CONFINTEA VI Mid-Term Review Meeting, in which the precarious conditions prevailing in youth and adult education are considered.

There are also overlaps with the international policies of youth and adult education such as CONFINTEA V, CONFINTEA VI and the Recommendation on Adult Learning and Education, whose approaches are still far from being realised in most countries.

In short, the proposal is to promote and consolidate comprehensive, inclusive and integrated policies – cross-sectoral and interdisciplinary – from a human rights perspective, in which education is holistic and integral. We are talking about policies implemented in specific programmes and projects with sufficient resources; policies which promote equality between men and women, including affirmative action for the most disadvantaged groups; policies that are centred on the contexts, interests and needs of the people they target, and in which the participation of all the sectors of society involved is fostered; policies which emerge from participatory decisions and in which the State lives out its role as a guarantor.

An additional and fundamental policy for progress is that governments should devote 6 % of GDP to the education sector, and that investment in historically disadvantaged areas such as youth and adult education should gradually increase. In addition, it is necessary to define policies not only from the perspective of education, but also in conjunction with economic and social policies, in order to mitigate existing inequalities and poverty, which have been on the increase (Civil Society Declaration 2013, ICAE 2015, Brasilia Charter 2016, UNESCO 2009, 2015 and 2017, CLADE 2017, FISC 2017).

The practices within youth and adult education in Latin America presented in this article contribute towards development. They have changed the lives of individuals and their families, in their environments, and at different territorial levels. However, the marginal situation of youth and adult education compared to education for children and adolescents is a structural factor that prevents its impact from being amplified, since it generates precarious conditions for its development, giving rise to a critical juncture.

On the other hand, we live in a world where often the only thing that counts is what can be measured. While the impact of youth and adult education can be identified, assessed, appreciated and shown, it can seldom be measured in the strict sense of the term. The reality is complex.

Hence the importance – to those of us who work towards and are committed to the right to the education of young people and adults and to the construction of a more just world – of systematising our experiences, highlighting who the participants are, the factors involved in the processes, the results and impacts, as well as the problems encountered along the way, all with the aim of valuing our work, socialising it and demanding other logics of reflection and action. Systematisation helps generate information that makes visible and positions both youth and adult education and the young people and adults who participate.

1 / By impact we mean the modifications of reality that are produced by a set of causal relationships; in this case, youth and adult education is one of these.

2 / These experiences were contributed by members and friends of the International Council for Adult Education (ICAE) of Latin America, to be included in papers presented at various international forums held in 2017.

https://bit.ly/2Lfcgcu

Bhola, H. S. (2000): Evaluación: contexto, funciones y modelos. In: Schmelkes, S. (Coord.): Antología Lecturas para la Educación de Adultos. Conceptos, políticas, Planeación y evaluación en educación de adultos, Aportes para el Fin de Siglo, Vol. II, 554-555. Mexico: INEA - Noriega Editores.

Campero, C. (2017): Reflexiones y aportaciones para avanzar en el derecho de las personas jóvenes y adultas a una educación a lo largo de la vida. Revista Educación de adultos y procesos formativos, 4. Chile: Universidad de Playa Ancha. https://bit.ly/2LYrsOx

Carta de Brasilia (2016): Seminario Internacional de Educación a lo largo de la Vida y Balance Intermedio de la VI CONFINTEA en Brasil. https://bit.ly/2BpP7Ds

CLADE (2017): Llamado a la Acción por el Derecho a la Educación de las Personas Jóvenes y Adultas: Hacia la Revisión de Medio Término de CONFINTEA VI, Lima, Peru, 17 August 2017. https://bit.ly/2KoDvQu

Declaración Conjunta de la Sociedad Civil sobre el Derecho Humano a la Educación en la Agenda de Desarrollo Post 15. El derecho humano a la educación en la agenda de desarrollo post-2015. September 2013. https://bit.ly/2n70zKn

Grupo de Incidencia en Políticas Educativas con Personas Jóvenes y Adultas (GIPE) (2018): La sociedad civil por la promoción y defensa del derecho a la educación con las personas jóvenes y adultas. Propuesta de agenda a las coaliciones políticas y candidatos. Mexico: GIPE.

Gómez, M. y Sainz, H. (2008): El ciclo del proyecto de cooperación al desarrollo (7th ed.), 98-99. Madrid: CIDEAL.

ICAE (International Council for Adult Education) (2015): Declaration of the IX ICAE World Assembly. Montreal, 14 June 2015.

ICAE (2017): Education 2030: From commitment to action. Statement from the Civil Society Forum – for the CONFINTEA 6 Mid-Term Review, 24 October 2017, Suwon. https://bit.ly/2O91Mwe

UNESCO (2009): Living and learning for a viable future: the power of adult learning. Final report. Confintea VI. Belém, Brazil.

UNESCO (2015): Recommendation on Adult Learning and Education, 24-36. Paris: Unesco and UIL.

UNESCO (2017): The power of Adult Learning: Vision 2030. CONFINTEA VI Mid-Term Review 2017. Suwon.

About the author

Carmen Campero Cuenca is a social anthropologist and teacher in adult education from Mexico who has dedicated more than 45 years to youth and adult education, 36 of them at the National Pedagogical University. She is a co-author and teacher of training programmes with various approaches, and has published extensively.

Contact

ccampero2@gmail.com

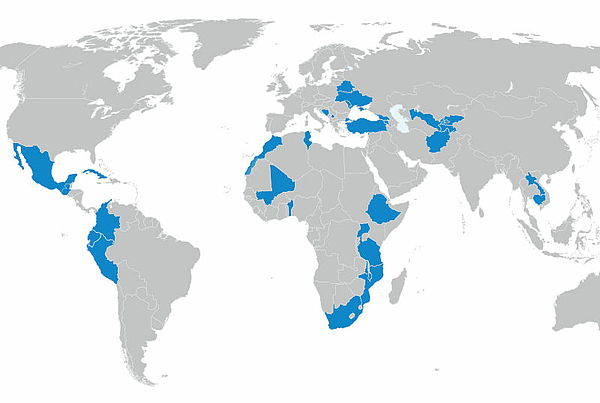

DVV International operates worldwide with more than 200 partners in over 30 countries.

To interactive world map