Interview by Johanni Larjanko, Editor-in-Chief of Adult Education and Development

Haldis Holst is the Deputy General Secretary of Education International. Born in Oslo, Norway, in 1960, she graduated as a teacher in 1983, after majoring in English and Physical Education. She has worked as a teacher in primary and secondary schools, and has been a union representative at local, regional and national level. She meets up with Adult Education and Development to reflect on how Education International works with teacher training, and what challenges teachers are currently facing in the world.

Good teachers are a necessary prerequisite for any quality education to take place, irrespective of the level of teaching. This is true regardless of the age of the learner. Good teachers are the key. The challenge is immense, as we see a lack of qualified teachers in so many places in the world, both North and South. It is a very complex question: How can we best recruit enough teachers, and how do we help them become really good at what they do?

Our main focus at Education International is to combat the trend of taking shortcuts, for example by lowering the requirements. We see a temptation in various places to lower them in order to increase the number of teachers, and thereby improve a country’s statistics. This is a very dangerous road to take. Statistics can never be more important than quality! But what is the best way to address this? There is no simple answer, as the situation varies from country to country. Let me give you some examples: The median age of teachers is rather high in many places. Here the challenge is to attract new teachers. How do you recruit young people into the teaching profession; how do you make the profession attractive to them? In some countries, the challenge relates to regional imbalances, where parts of the country may have a rather highly educated teacher group, whereas other, often more rural areas, are worse off. Here the issue is about equal distribution. How do you make sure there are enough good teachers in the whole country? The challenges vary, and so do the solutions. I think the first thing that each country needs is a national strategy on how to train and support teachers.

That’s a tough question to give a general answer to. It is so different from place to place. If I look at it from a positive perspective, education has received a lot of attention as an individual right, including the right to lifelong learning. Education is also increasingly in focus as a tool to reach other goals, not least the Sustainable Development Goals and the 2030 Agenda of the United Nations. In many countries, education is considered the best way to combat poverty, fight for a more sustainable world, create more jobs, and so on. As a result, politicians are increasingly aware of the need to invest in education. And that is in my opinion a positive trend. At the same time, there is still a gap between rhetoric and action; there is still so much to do. It is not enough to fund teacher training, or to make the field more attractive. You have a lot of infrastructure to build up. Things like decent salaries, secure employment, functional working conditions. That is what Education International is fighting for. To sum it up: We feel there is broad support in theory, but not yet always in practice.

Our solution here is to very actively support our member organisations, who are all working on the national level. We want to help them engage in the policy debate in their respective countries. The best effects are reached when they succeed in both pushing for change and suggesting some solutions. Another tool is the Global Partnership for Education (GPE), that is set up to help countries reach Goal 4 of the Sustainable Development Goals. This is aimed at the countries with the most urgent needs and which are trailing behind. The first thing this partnership does is to give financial support to develop an education sector plan. The second thing is initiating a civil dialogue with various stakeholders. We think these steps could be useful in developing all levels of education. It is also a good way to inform politicians about our needs. Finally, this also helps to keep a watch on what is going on, making sure that the policy is not just a piece of paper.

It’s difficult, but there are some things we can do. Together with UNESCO we have worked on international standards for teachers, the so-called EI/UNESCO Global Framework of Professional Teaching Standards. That says something about where you must reach to be acknowledged as a professional in this field. These standards are being piloted by UNESCO in some parts of the global South as we speak. Fortunately, many countries have already developed a sort of professional ethics in teaching. That is a good start, but then these too must be checked for quality. This is where the international standards come in. To fit different needs and contexts, an international standard cannot go into depth, like stipulating the number of years you must study to become a qualified teacher or a universal curriculum. But what they can do is describe the competences you need if you want to be considered a professional. So more than anything they tend to be a framework and a reference point when developing national policies.

Ah, good question. I admit we at Education International should be better at mentioning adult learning, talking about it, and including it in our work. Already today we also represent higher education and vocational training, but non-formal and informal adult education falls a bit below our radar at present. Nevertheless, all levels and types of education have a role to play, and we can certainly become better at including a wider scope in our rhetoric, and in our work. I can see challenges at both ends of education, at the very first stages, and then at the later stages. We are working to quality assure early childhood education, as well as learning taking place outside of the formal system. We would like to get more involved with actors in this sector. Some of our members are active in it today, but many of their teachers are not reached by teacher education. These are the ones we cannot currently reach, those active in adult education, but without a background as trained teachers. They are seldom members of teachers’ unions. We have increased our efforts considerably in recent years to reach this group we call education support personnel, as they are of course important. This group includes all those who are involved in education, but are not trained to be qualified teachers.

Yes! I completely agree. It’s the same as for those taking care of early childhood education. They are also doing a very important job, but their status is unclear in many cases. Both of these groups need support; they need help to get organised. For adult educators outside the formal system it’s about building bridges towards working life. It is also about making sure they are given the opportunity to study, to get the qualifications they need to do an even better job. Many have extensive practical experience, but may lack the formal recognition of a degree. This is also true for a lot of teachers in vocational training.

Haha, yes you are right, this all makes the challenges even more complex. On the one hand we have big differences between countries that are preparing learners for a digital world and countries that have not even started on this journey. The latter may lack equipment, or the classroom may be without electricity. Access to technology is often the first hurdle. This is a debate on equality, where we see no direct conflict. Everyone seems to be in agreement about the need to improve. Then the IT skills of the teachers also vary greatly, and there is a need to include this in further training of teachers on all levels of education. We will all need digital competences to cope in the future, teachers and learners alike. I also think technology offers good tools for learning, where teachers can create new learning arenas, and support current ones. Take access for example. Technology promises to let us reach groups we currently cannot. We should try to see the possibilities without losing sight of the digital divide, and fight to overcome it. Finally, we need to act as watchdogs and remind decision-makers that machines cannot replace human teachers.

Well, in our education policy paper we state that the teaching of teachers includes three elements. We have the initial teacher training, the introduction to the work as a teacher, followed by further education. All three elements are equally important, and are necessary to ensure good quality. Of course some knowledge is constant, and learning it once is enough. But a lot of knowledge gets outdated, and we also have new knowledge appearing.

Hmm. I think our members will give different answers to that. Some strong associations will say that EI can do things they cannot. For example by representing their interests in the dialogue with OECD, UNESCO, or the European Union, to name a few. We are often acting as the critical friend here, giving the teachers a voice at the table. Smaller members primarily need us to strengthen their competences. They also want our help to build strategic plans and the like. What all our members have in common is the insight that education is increasingly affected by global trends and aims. Much of the political agenda is run on a global scale, even if the implementation is national. We think a major challenge to education is the increasing interest in the field by global commercial actors, looking to conquer new markets. Now there are also many private actors who have a long-term commitment in education, and are serious about quality. They are generally not a problem. Companies looking to expand from education offered to a small elite to education for the masses, these are new in our sector, and they pose several threats. We see them targeting in particular poorer countries in the global South. These private actors generally do not like Education International very much. And yet we do not consider them “the enemy”. They are working on a market. It is the responsibility of governments to set standards, develop a good quality assurance system and to not lower requirements. And it is our job to help governments remember that.

Education International was founded in 1993 as a merger between two organisations. The merger that led to the formation of EI not only created the world’s largest, most representative global, sectoral organisation of unions, but also brought together the two powerful traditions of education trade unions and professional organisations. The new organisation made it possible for free quality education for all to become one of five global policy priorities. Other priorities include promoting the status of the teaching profession, improving professional standards, terms and working conditions, and countering trends towards de-professionalisation. More information at https://ei-ie.org

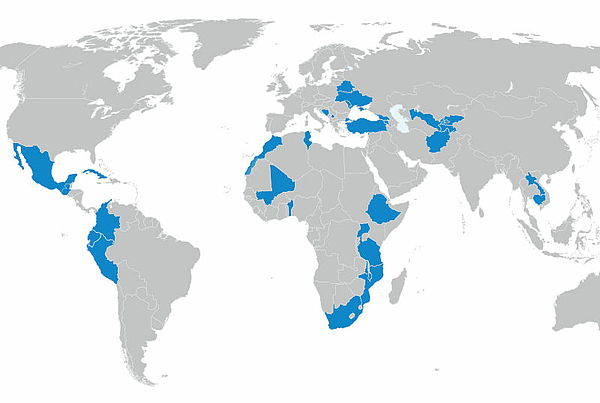

DVV International operates worldwide with more than 200 partners in over 30 countries.

To interactive world map