Kadiato Diallo/Wolfgang Leumer/Yasmina Pandy

In South Africa, as in other countries in the world, the AIDS epidemic is spreading rapidly, and the number of sufferers and carriers is constantly rising. There is an obvious link between poverty and AIDS, so that the fight against poverty is extremely important and presents adult education with a new challenge. HIV/AIDS Learnership programmes are being developed under a pilot project, with the aim of reducing the socio-economic effects of the condition and slowing the spread of the virus. Progress to date has been very successful. What follows is taken from the report on experience with the project by Kadiato Diallo, Researcher HIV/AIDS, Wolfgang Leumer, head of the IIZ/DVV Regional Office in South Africa, and Yasmina Pandy, Programme Officer Adult Learning Network and Project Coordinator of the Learnership Programme.

Kadiato Diallo/Wolfgang Leumer/Yasmina Pandy

HIV/AIDS Learnership Programme and Poverty Reduction

Introduction

HIV/AIDS is one of the fastest growing diseases around the world, and more so in Sub-Saharan Africa. It is estimated that by 2005, six million South Africans will be infected by the disease and that 2.5 million people will already have died of the disease. This is leading most governments and organisations to explore more cost-effective ways of providing care to people with AIDS. One of the most widely promoted strategies is to provide care for people at home rather than in hospitals since hospital in-patient care is the most expensive way of providing care to people with AIDS.

In South Africa as is the case in many developing countries one cannot ignore the connection between poverty and HIV/AIDS. Poverty does not cause HIV/AIDS, but in many cases it worsens it. There are many ways in which that poverty can place people at a greater risk of acquiring the virus and can worsen it for those already infected.

-

Unemployment and poverty often force women to take on jobs as sex workers.

-

Migration of men to cities because of lack of jobs in rural areas often leads to multiple sex partners therefore increasing the risk of both HIV and sexually transmitted diseases (STDs).

-

A person who is HIV positive and poor often finds it difficult to access health services or medication necessary to keep him/her healthier for a longer period of time.

-

An HIV positive person who is poor might not be able to afford the necessary foods and vitamins to stay healthy. This may weaken the person and increase the person’s chance of getting sick with AIDS.

In South Africa, both civil society and government have implemented a variety of programmes to deal with the demands and challenges brought about by the pandemic. However, research has shown that many of these programmes often have a narrow focus and either deal with a specific aspect of the HIV/AIDS issue, i.e. prevention, education and awareness, counseling, home-based care, etc. or a combination of these aspects.

In view of the importance of adult learning to relate to this difficult situation having to cope with huge impacts on the communities IIZ/ DVV had submitted a proposal in 2002 to the funding ministry in the framework of a newly created budget line on poverty reduction. The objective of this proposal was to show the role that volunteers could have in responding to the challenges in both rural areas and in South African townships. The proposed pilot programme intended to reach out to a sample of volunteers who would be trained in a holistic way to deal with all aspects of the crisis in their respective communities. The pilot was composed of groups of volunteers selected and identified by a range of NGOs in the Western Cape province, KwaZulu Natal, Limpopo Province and the Eastern Cape. Later on the sample of beneficiaries was extended to include trainers or facilitators recruited via member organisations of the Adult Learning Network (ALN). This extension was made possible because of a matching grant from the Cross Cutting Fund of the German Agency for Technical Cooperation (GTZ). In the following report we often distinguish between the volunteers or learners from the initially proposed Pilot and the Extension group.

| The Course The Skills Programme Fieldwork |

Initially the programme was run and managed by staff recruited by IIZ/DVV. However, ownership of the programme was vested in the stakeholders involved and should in the process be deployed to a dedicated working group under the auspices of the Adult Learning Network (ALN). One of the major innovative aspects of the programme was to structure the training in line with requirements of the National Qualifications Framework. This means that trainees in the programme would in the end obtain a level one qualification. With such a qualification at hand employability for the beneficiaries of the programme could be increased and further rollout of the training could be facilitated within the framework of an accredited skills programme. Accredited skills programmes are the building blocks for a learnership. A learnership is a programme that contracts the provider, the learner and the prospective employer (health service, local government or NGO), in need of skilled and competent intermediary agents in the field of HIV/AIDS. 60% of a learnership is workplace orientated. Learnership training is financed by the Department of Labour. The funding usually comes from the SETAs (Sector Education and Training Authorities). All SETAs have been asked by the Department of Labour to use some of their funding for the overarching issues of HIV/AIDS training. The proposal had identified this resource opportunity as a way to secure the sustainability of the programme in the long run. Poverty alleviation would on the one hand be effected directly for the beneficiaries of the training, as it would lead to a qualification for them and thus increase their employability. On the other hand indirect effects are expected from the impact that their skills and their application should have on all members of those communities where volunteers or other multipliers apply their knowledge and become agents of change and of coping strategies.

In line with these and the underlying assumptions, the Pilot programme was named the HIV/AIDS Learnership.

What the HIV/AIDS Learnership programme strives to achieve is to address the pandemic by using a holistic and developmental approach. It is a response to the need for a single comprehensive health care programme built around HIV/AIDS for voluntary caregivers in South African communities. The purpose was to equip thousands of voluntary carers in the communities with a wide range of knowledge and skills, thereby enabling them to have a noticeable impact on their own environment.

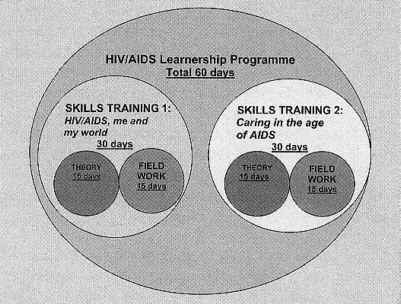

This led to the development of two skills programmes (SP). SP 1 is more theory-based and covers factual information about HIV/AIDS (prevention, transmission, etc.) and general health and development and environmental issues. SP 2 is more focused on practical components of home-based care. Both programmes consist of a theoretical and a practical part. The theoretical part is covered in 30 days of tuition and the practical part in 30 days of fieldwork in which the learner’s acquired knowledge is implemented in their community. This practical caring component in particular will be further expanded and developed in line with the Ancillary Health Care Certificate qualification (a Level 1 qualification, accredited and registered by the Health and Welfare Sector Education and Trainig Authority SETA).

By eventually providing a qualification, this programme gives formal recognition for the work of these committed volunteers, not only by improving their current status but also by potentially increasing their employability. Sustainability will be maintained through the accreditation of the programme with the Health and Welfare SETA that is currently in progress.

Two rollouts took place in 2003 (Pilot and Extension) and resulted in the training of approximately 240 volunteers and 34 trainers in 7 provinces. The process and results of this implementation will be discussed below.

The HIV/AIDS Learnership Programme

The HIV/AIDS Learnership programme was developed to contribute to the reduction of the socio-economic impacts of the HIV/AIDS pandemic in South Africa and to help slow down the spread of the virus. The goal of the project is to train voluntary social caregivers in affected rural and semi-urban communities in HIV/AIDS prevention and social care and to provide them with a qualification. This goal has been met to a great degree as the brief discussion of the specific aims will show:

1. An educational plan for HIV/AIDS social workers has been developed. The programme follows a comprehensive, development- focused and learner-centred approach for health care in communities, encompassing health promotion, developmental services, and preventive health care within varying contexts, sectors and organizations in order to meet the basic HIV/AIDS education, advisor and home-based care needs of the target communities. The course as it was implemented in 2003 consists of two skills programmes (SP) and stretches over a 60 day period. Each SP consists of 15 days of course work and 15 days of fieldwork, when learners apply their newly acquired knowledge in the communities.

2. The Health and Welfare Sector Education and Training Authority is willing to register the course with South African Qualification Authority. Because an application for a new learnership could take up to five years and would require an extensive consultation and lobbying process, it was decided to opt for an alignment of the present programme with the existing Ancillary Health Care qualification. The registration could be completed in a year’s time, which would allow the early provision of formal recognition for the sterling work done by the volunteers.

3. The alignment of the existing material with the existing unit standards of the Ancillary Health Care Qualification, discussed above, is currently in progress. A group of writers are developing a whole new section, including basic life support and/or first aid procedures in emergencies, life orientation, natural sciences etc.

4. The programme has been rolled out in seven provinces. The implementation took place in two stages. The first PILOT group of 156 learners was trained from March 2003 (in KwaZulu Natal, Limpopo Province, the Eastern and Western Cape). The additional 84 learners of the EXTENSION group (in the same four provinces as well as in Free State, Gauteng and North West province) subsequently started training in August 2004. The partners in the Northern Cape did not partake in the programme as planned due to their absence from the Training of Trainers workshop.

5. Twelve qualified trainers have been identified and have been prepared intensively for their role as implementers. The partners in the pilot group were left with the selection of four candidates to meet the agreed criteria for a facilitator. During the 3-day orientation in November 2003 it became apparent that a number of the 20 candidates lacked training experience for the satisfactory implementation of the programme. Two trainers resigned from their organizations before the start of the programme. The overall drop out rate in the pilot was 47%. The drop out rate in the extension group, where two trainers per province were selected (a total of 14) was 14%. Candidates from the various Adult Learning Networks in the country were experienced trainers. One trainer took the opportunity to study full time, the other trainer had a large group of ABET (Adult Basic Education and Training) preparing for the Matric examinations and did not participate in Skills Programme 2.

6. A network of providers has been structured. In 7 provinces relationships with service providers were established. All service providers in the pilot group had experience in the field of HIV/AIDS. The ones in the extension group did not but the many volunteers from this group were already involved in HIV/AIDS organisations. Due to the extension of the programme, a lot of the increased workload had to be put into coordination and support for facilitators and less time could be spent on extensive networking. Several service providers have been identified, however, in KwaZulu Natal and the Western Cape. Also, a database of organizations involved in HIV/AIDS has been established. Selected organizations will be invited to an orientation workshop in 2004 for future roll-out.

7. PR through road-shows, LCF (Learning Cape Festival), GTZ (German Agency Technical Coorperation) mainstream projects. The programme was promoted and showcased at all events of the Learning Cape Festival. A presentation was held at the Adult Learners Week (sharing a platform with Professor Rybicki) and at the Adult Learners Week in Bloemfontein, Free State.

8. Commercial publisher to produce learner and facilitator manual in English

9. Translation into 3 national languages

Both of these aims will be dealt with once the programme has been aligned with the Ancillary Health Care Certificate and the accreditation with the Health and Welfare Health and Welfare Sector Education and Training Authority has been granted.

Despite the challenges that we came across during this first implementation phase, the programme was a definite success.

This has been confirmed again and again by the participants, learners and facilitators, but also by representatives from the Health and Welfare Sector Education and Training Authority HWSETA and other stakeholders. For the learners this course offers in the first place tools for hands-on contributions in their communities and before that in their own families and circles of friends. The knowledge and skills they receive gives them a confident voice to address the issues related to the HIV/AIDS pandemic in a concrete manner. These volunteers are messengers of the knowledge on how to deal with the daily challenges of living with HIV/AIDS that is so urgently needed in those areas but often does not reach the people.

By raising awareness, improving the lives of people living with HIV/ AIDS, by caring for them but also by helping them access service structures for example, a noticeable contribution to the reduction of the spread of HIV/AIDS has been made. We are not talking about overnight changes here of course, but ultimately the increased knowledge acquired in our programme has had two major effects on the affected communities.

Results from the Fieldwork

The fieldwork consisted of two parts each consisting of 15 days. Each skills programme was followed by 15 days of fieldwork. This was done for organisational reasons and mainly to use the limited time available most efficiently. The fieldwork gave trainers sufficient time to prepare for the second skills programme.

During the 30 days of fieldwork, learners were required to conduct a minimum of 60 visits (2 per day). The local coordinators in each province selected the clients for the fieldwork. In some cases learners were already involved in community work and had their own clients before the training. Depending on the planning of training in the different provinces, some groups did the whole 30 days of fieldwork in one stretch.

In some of the provinces where the first part of the fieldwork was done after Skills Programme 1, it was found that even though the general feedback from the learners after the training of SP 1 was that they felt confident to implement their knowledge in the field, when actually engaging with the challenges in their communities, they found that the skills they had acquired were not sufficient for the learners who did not have prior experience in home based care.

A strong recommendation was therefore made by learners to first complete all the formal tuition before going commencing with the fieldwork.

Other groups contacted clinics that placed the volunteers with clients in the communities closest to them.

In order to monitor the fieldwork, every learner had to complete a visit report for each visit, indicating date and time of the visit, condition of the client and tasks performed (also difficulties encountered) during the visit.

Pseudonyms were used for the clients so that confidentiality would be guaranteed. At the same time it was also a way to track how a particular client was visited and cared for and the condition of the client between visits.

The discussion groups held during the site visits were useful in that they gave more contextual insight into the progress of the fieldwork.

Trainers and/or coordinators of each group were asked preferably to have weekly meetings with their learners to share experience in the field and discuss upcoming problems as well as solutions. The staff of IIZ/DVV recommended a minimum of two meetings per month. Minutes of these meetings were to be handed in as part of the report submitted by the trainers at the end of the programme.

The volunteers mentioned that they were faced with serious problems in the communities. These problems were said by them to be interlinked, but went far beyond just immediate health care. Some of the examples cited by the learners included the following:

Poverty often does not allow people to provide good nutrition even if they have been made aware of its importance, a referral to the clinic becomes useless if no transport is available, and a grant cannot be applied for if one does not know how or does not have a valid ID,

to mention just a few issues that the volunteers had to deal with.

Nevertheless, the feedback about the experience was very valid and positive. The volunteers stated that the people in the community welcomed their work. Although many of the volunteers are still relatively young they said that they had no problems communicating with the older community members. Topics such as sexuality and HIV/AIDS were still not discussed as openly as they should be. In some areas they said it was also culturally not allowed for the younger generation to address the elderly about issues like sexuality and HIV/AIDS and that this sometimes caused problems for them.

Men seem to be a challenge for the female carers. The volunteers stated that women in the communities were often afraid of their men and did not go to the clinics openly. The regular visits from the volunteers made the men (as well as the women) feel more comfortable with the issue.

Another difficult target group that they mentioned was young people. They stated that in some areas young people, who were at such great risk, often still did not take the issue of HIV/AIDS seriously. In other areas, where the young volunteers were already involved in youth projects, where they were recognised and accepted, taking and convincing young people was a lot easier because these youth belonged to organised structures.

Some volunteers cited that they organised awareness days at schools for example as part of their fieldwork and reported this in their visit report. They felt that they were making inroads because the teachers from these schools were inviting them to come back for more education and awareness programmes. The volunteers indicated that the students at these schools felt free to talk to them as people of their own age rather than their teachers and also that the information they received was a lot more plentiful and relevant than that provided to them before by their schools.

One serious problem that was experienced by several volunteers was issues related to superstition. The volunteers mentioned that they often had to call in their trainer or coordinator to assist them in dealing with clients who responded to the volunteers with superstition. The volunteers also indicated that they often called in the help of the trainer when they felt inadequate to deal a particular situation on their own.

Many of the volunteers stated that the use of a uniform would help them to be recognised as more ‘official’ service providers.

On the whole, the feedback from the volunteers who participated in the group discussion, feedback from the meetings between volunteers and their facilitators and reports from their trainers suggest that there was a good spirit amongst volunteers and their clients and that volunteers found that the work they did in the communities greatly benefited and empowered their communities.

Client Satisfaction

Client satisfaction was assessed through interviews with a selected sample of 3-4 community members or households in each province who received service from the learners. The trainer and/or coordinator in the area were responsible for the selection. Although it would have been desirable for the evaluator to choose clients randomly in order to avoid the risk of only the most satisfied clients being selected and to increase validity, this was not viable from an organisational point of view.

Interviews were conducted in the following areas:

-

Eastern Cape (Extension group)

-

Free State (Extension group)

-

Limpopo Province (Pilot group)

The reason why interviews were not conducted in all provinces is that in several provinces the fieldwork had not yet commenced when the evaluators came on the site visit.

Some groups had difficulties organising and coordinating their fieldwork. In some of the provinces (Gauteng and Limpopo) the fieldwork had not started as negotiations were underway with local clinics regarding the placements of volunteers. Another difficulty that volunteers had was that they were restricted to providing services for clients only in the surrounding areas because of transport difficulties. The project did not make funding available for volunteers to travel to distant areas. Often, these distant areas are the areas where the need for services is greatest.

In other cases transport to the areas where fieldwork was conducted was not available or the areas were inaccessible by car. Sometimes time constraint prevented the evaluators to conduct interviews.

Lastly, not all provinces could be visited due to lack time and staff availability. On average, 30 minutes were spent in each household. Either one of the facilitators or the director of the organisation accompanied the evaluators for introduction and translation.

Interviews were guided by the following questions:

-

Introductory questions about well-being, diagnosis and living conditions.

-

How is the volunteer helping you/What kind of tasks does the volunteer perform for you?

-

How has your life improved since the volunteer started visiting you regularly?

-

What other service/help would you require from your volunteer?

How many of the clients are in fact HIV positive is difficult to estimate, as many do not know their status, others wish not to reveal it. Sometimes the family members told the evaluators that the client was HIV positive while the client himself denied it. Only a few openly shared that they had AIDS. The volunteers were confronted with opportunistic diseases, such as TB as a result of infection with the HIV virus, but there were also cases of mental illness in some areas.

In some areas the clinics are inaccessible for the people either because their condition does not allow them to travel, sometimes because of a lack of money for transport. Therefore, caregivers have to deal with a set of symptoms that have never been professionally diagnosed.

In many households women take care of families (children mostly), including at least one client, on their own. Financially they do so often from a small (old age or disability) grant. Other clients barely manage to take care of their own. Poverty is omnipresent. The role of the volunteer ranges from performing basic housekeeping tasks such as grocery shopping (especially when the client is restricted in mobility), cleaning, washing, cooking, but also changing bandages, and helping the client to wash. It also involves a lot of counselling and advising from health education to support in applying for grants, and also simply listening and showing the people that they are not alone in their situations, and taking some of the pressure off the ones who care for the clients on a daily basis.

One client for example, said that his depression had gone since he started talking to the volunteer regularly.

As mentioned above some volunteers in Limpopo province started the fieldwork after Skills Programme 1. The interviews during a site visit after SP1 showed that the tasks performed by these volunteers were still quite limited as this group also lacked prior experience in community work.

This was not the case in other groups that started fieldwork before completion of the whole training, where all clients said that their situation had improved since the volunteers started assisting them.

When the particular area in Limpopo was visited for the second time after Skills Programme 2, the situation had improved quite significantly since the volunteers were able to engage more efficiently in their fieldwork and the effects could be observed among the clients.

Again it was emphasised that it was necessary to first complete the theoretical aspect of the entire training course before starting with the fieldwork.

In one of the affected areas in the Eastern Cape, a client indicated that she benefited a lot from the coping strategies the volunteers offered, from basic health and hygiene rules, to help with grant applications etc. Since women often have to take care of the sick family members as well as provide for the income, the additional support from the volunteer is more than welcome and has a great positive impact.

On one side they remove a lot of strain from the caring family member and on the other they help to improve the condition of the sick client.

The trainers were very involved in the coordination of the fieldwork and often helped solving problems that arose from difficulties that the volunteers were not equipped to tackle on their own. One woman suffering from the effects of AIDS, who the evaluators had visited just recently, was apparently left to herself by her sister who had too little food to feed her own family and chose not to care for her any more. In cases like this contacts to the relevant authorities were made.

Despite the tragedy of such events, volunteers started building networks with key players in their communities and increased the effectiveness of their work.

Recommendations

The stakeholders of the project made the following recommendations:

1. That the theoretical part of the programme should be completed first before embarking on any fieldwork.

2. Placement of learners with clinics, NGOs, hospices and other institutions should be done prior to the commencement of the programme. These arrangements should be negotiated with municipal and provincial government.

3. Volunteers should have first aid kits.

4. Volunteers should have a uniform that gives them ‘official’ status in their communities.

5. The ideal classroom size should be 12 and the maximum should be 25.

6. Funding should be made available for transport so that volunteers can work in communities most affected and infected.

Conclusion

Despite the challenges that we came across during this first implementation the programme was a definite success.

This was confirmed again and again by the participants, learners as well as facilitators, but also representatives from the Health and Welfare Sector Education and Training Authority HWSETA and other stakeholders.

For the learners this course offers in the first place tools for hands-on contributions in their communities and before that in their own families and circles of friends. The knowledge and skills they receive gives them a confident voice to address the issues related to the HIV/AIDS pandemic in a concrete manner. These volunteers are messengers of the knowledge on how to deal with the daily challenges of living with HIV/AIDS that is so urgently needed in those areas but often does not reach the people.

By raising awareness, improving the lives of people living with HIV/ AIDS, by caring for them but also by helping them access service structures for example, a noticeable contribution to the reduction of the spread of HIV/AIDS has been made. We are not talking about over nightchanges here of course, but ultimately.

On another level, the qualification in which this programme will result in the near future equips these volunteers with a currency that should improve their standard of living by increasing their employability, thereby also contributing to poverty alleviation at the same time.

Further research has to show to what extent the qualification will lead to the employment of these volunteers. Another future research question that needs to be answered is how far the valuable services provided to the affected communities are sustainable on a voluntary basis only.