Jorge Aliaga Murillo

In the era of the Internet, we tend to overlook another medium that was once regarded as an invaluable instrument of social work and participation – radio. Radio is a medium that was used to address the pressing issues of the day while being an important source of entertainment, particularly considering that it was well-suited to combine with other media and methods, and easy to place in the hands of the stakeholders themselves. Especially for people who are still excluded from the Internet, radio continues to be a highly effective medium today.

Particularly in Latin America educational broadcasting has a long tradition. One of the main advantages of this type of learning has always been that it is even accessible in remote rural communities where infrastructure is lacking. It could be heard by almost everyone who was somehow able to afford a transistor radio and at least occasionally able to buy the required batteries. Even today, radio often remains the only source of information and entertainment for the rural population. People can listen to the radio on their way to and from their fields, while doing housework, during mealtime – in short, anytime and anywhere.

Another considerable advantage is that it does not necessarily involve expensive technical equipment or significant material investments to set up a local transmitter. A community radio station can be launched on a budget of a few thousand euros or dollars.

It is not costly or difficult to arrange for radio programmes to be broadcast in all the different languages of the population. This makes radio a particularly suitable medium for fostering multilingualism in countries where many regional languages are spoken alongside the dominant language.

Radio lends itself well to covering topical issues of local interest and concern. There are no complex publication routines that require time-consuming investiga tions, drafting and redrafting of texts, editing, typesetting, proofreading, printing, binding, and elaborate systems of distribution. The work only involves preparing a script and recording the broadcast. Including interviews in the programmes as part of the investigation process conveys the direct and undistorted nature of the information that is being communicated. Interviews capture the attention and interest of listeners and help to keep them actively involved.

A local radio station is not obliged to offer a full-time programme of high editorial quality seven days a week. That is not what community radio is about. The idea is rather to provide a few hours of commentary and information each day, interspersed with lots of music, in a regular schedule of broadcasts at times when people are available to listen.

The experience of many community radio efforts shows how rapidly a rural population or community neighbourhood can be mobilized to run “their own” radio stations. Community members nearly always master the technical aspects quickly. Taking on positions of responsibility in the operation of a radio station appeals especially to young people who tend to identify with the work. It creates a “we feeling” that is an important motivation in the development and analysis of personal interests.

Organizations committed to the promotion of social development have recognized that radio is a good way to gain entrance to groups living on the margin of society and to win the confidence of their members. Radio serves as an important component of the work of such organizations. Broadcasts are combined with other elements – theme-oriented booklets, example given, which reinforce the messages in the radio programmes, and activities conducted in the communities themselves tie in with the topics discussed on the radio and in the booklets. Together such efforts pave the way for concerted action. Often, but not always, it is non-governmental organizations which adopt this approach. In Latin America radio work was frequently pursued or fostered by church organizations. National literacy programmes in vari ous countries, however, have also worked with educational radio broadcasts.

The following contribution about radio ECORA in Bolivia describes the motives, goals, contents, and methods of a radio project in an indigenous region where the people live in situations of cultural and economic domination and are still in the process of defining and defending their own interests. Radio offers them an opportunity to gain new appreciation for their autochthonous languages and to practice using them. It supports the indigenous population in their search for their own identity and self worth. The project described in this article took place thirty years ago, which is a long time in the development of our field of continuing education. The methodological approach, however, is just as current as its objectives.

The example of ECORA, which Jorge Aliaga Murillo describes from his own expe rience, shows that in countries where acute situations of conflict exist, community radio projects linked with socially committed efforts to represent the interests of disadvantaged groups, are capable – and perhaps even obliged – to assume the role of opposition, even if it involves confrontation with the State and its mechanisms of control. It is also clear from the history of ECORA, which was not able to survive under the Bolivian dictatorship, that such projects cannot disassociate themselves from conflicts resulting from the stands they take.

The closure of ECORA, however, was not the end of commitment to promote com munity radio. Other projects were able to build on the experience gained from ECORA, and they further developed their methods in similar endeavours. Radio San Gabriel was one such project that received support from DVV International for its bilingual measures. The work of Radio ECORA was carried on by “Qhana”, an organization which is still active today not only in the province of La Paz, but throughout the entire country. And to return full circle to where this introduction began, Qhana also maintains Internet presence at the following website: http:// www.qhana.org.bo/

ECORA – Community Education through Radio

An experience in community education in Bolivia’s Altiplano

Bolivia’s Altiplano, a region populated by peasant farmers of Aymara origin, was the site of an unparalleled community education experience during the era of the military dictatorship. Various institutions and NGOs later built on the accomplishments made in terms of educational policy and methodology. The present article seeks to summarize the most relevant aspects of this community education project and to provide a systematic overview of the experience.

Introduction

This chronicle was written as a tribute to the work of one of the educators on the team who participated throughout the entire realization of the community education initiative that developed between March 1977 and July 1980.

The initiative in question provided occasion for closer analysis and critical reflection in view of its relevance as a community education experience during the era of the military dictatorship and the period of transition to democracy in Bolivia. The objective of the present essay is to share what was learned in the way of educational and methodological accomplishments and to gain insight into the project’s limitations. Rather than an evaluation in the strict sense of the word, the following is intended as a retrospect.

This paper will first consider the main determining factors of the context in which the project developed: the national political system, the role of the NGOs, and the situation of peasant agrarian unions.

Within this framework, the beginnings of the ECORA project will be explored in a discussion of the team and how it was organized, the plan of action, the measures that were conducted, the methods that were used, the processes that took place, and the project’s outcome. Lastly, conclusions will be drawn with a look at some of the lessons learned during the course of the experience.

Background

A brief description of the context in which the experience was initiated and developed is necessary for a better understanding of the evolution and later termination of the ECORA project.

Political life in Bolivia has a dynamic quality that is frequently seen as the manifestation of instability reflecting a climate of discontent issuing from a very fragmented social structure with a broad base of poor indigenous farmers who support the mestizo middleclass sectors of the population. The model of economy based on the extractive use of natural resources only brings benefits to the sectors in control of power – the urban elite and groups associated with foreign capital.

In 1971, a military coup from the right stifled the activities of social movements which had been seeking alternative political solutions, especially since the guerrilla campaign led by Che Guevara in 1967.

Using political repression and economic measures financed through the build up of the external debt, the military dictatorship under the leadership of Colonel Hugo Banzer sought to institutionalize the regime.

A parallel scenario began to emerge during the 1970s, as the first Bolivian NGOs started developing new concepts and initiatives. Their work together with groups of impoverished farmers was funded in some instances by the Catholic Church and in others within the framework of international cooperation.

It was against this background that the ECORA programme came into being. In 1976, the Ministry of Education set out to implement a comprehensive rural educa tion programme under the title Proyecto Educativo del Altiplano. The programme was mainly geared to the school system. In 1977, on the recommendation of the programme’s designers, an agreement was concluded between the Ministry of Education and the Asociación de Educación Radiofónica de Bolivia (Association for Radiophonic Training in Bolivia), entrusting ERBOL with the task of carrying out the community education component of the programme in farming communities located in the vicinity of Lake Titicaca in three regions of the Department of La Paz (the provinces of Los Andes, Omasuyos, and Manko Kapac).

ERBOL organized a multidisciplinary team to plan and implement a community education project. As the name chosen for the programme indicates – ECORA, or Educación Comunitaria y Radio (Community Education and Radio) – the medium of radio was to play a fundamental role in promoting community education. The ERBOL radio network brought a long tradition of experience in rural education to the initiative, including the numerous literacy learning programmes which it had produced during the latter part of the 1960s.

Designing a concept for the project cycle was the first step in the work, although contact was initiated almost immediately with the 30 communities that had been selected as focus groups.

The project relied on the Ministry of Education for its funding. Payments were very frequently delayed as a result of bureaucracy.

Contact between the Ministry and the Altiplano community education projects was very formal, and as a result of differences in approach, relations fluctuated between periods of tension and phases of closer cooperation and coordination. Since the communities reached by ECORA were not the same as those where the school-based interventions of the Ministry took place, ECORA enjoyed a relatively high degree of autonomy in its work.

Bolivia’s Altiplano

Source: Jorge Aliaga Murillo

The Design of ECORA

Basing their approach on the experience of various NGOs, the ECORA team started developing a concept for community education that would enable them to propose innovations in an atmosphere of collective construction. The main focus of the concept reflected Paulo Freire’s notion of the participatory processes of conscientization that are necessary for social transformation and cultural recuperation to take place.

Project plans were developed along these lines, leaving room to accommodate unforeseen developments in their practical implementation.

The institutional structure for the work of the project was designed to be simple and functional, and can be summarized according to the following scheme:

The Radio Programmes

The daily radio programmes, which were broadcast in the Aymara language (one hour in the morning and half an hour in the evening), rapidly attracted a large audience. The members of the communities identified with the characters in the radionovela (radio soap opera) and were able to relate to the news broadcasts, which featured interviews with community leaders and authorities, and covered issues of rural interest.

The ECORA programmes confirmed what programmes of other socially-oriented institutions had already demonstrated – that radio broadcasts have a significant impact on peasant farming communities if they are tailored to the interests and culture of listeners.

The programme format was highly varied. Initially, broadcasts were designed in the form of a radio magazine. To avoid the risk of fragmentation, however, a more simple structure was adopted. A summary of news items of national and regional interest was followed by commentaries in dialogue form, the introduction of a topic of central concern, the transmission of an instalment of the radionovela (with a dose of humour), and the presentation of questions for debate. The programme was concluded with a series of announcements and information about coming events to which the public was invited. Contributions were interspersed with autochthonous music from the region.

The interviews and progress reports on community initiatives served as direct channel for feedback. This permitted intense and dynamic communication.

Polls were conducted to determine levels of acceptance and coverage, as well as the main audience demands. Poll results, reception indicators, listener visits to the radio station, letters, and recordings all served to demonstrate that the radio programmes had a very large following and that the broadcasts enjoyed a high degree of acceptance in the communities.

Several factors contributed to the success of the radio programmes:

- Producing the programmes in the audience's native language – in the present case Aymara – gained the sympathy of the communities and facilitated their comprehension. The use of this approach followed a long tradition of native language radio programmes in Bolivia.

- The radio team sought out new formats for their broadcasts, e.g. newscasts geared to Aymara campesinos, and radio series such as the radionovela.

- They organized interviews, sought opinions, and focussed on cultural reevaluation.

- The project was staffed by professionally trained radio operators who sought to produce recordings of high technical quality.

- Broadcasts were scheduled to accommodate the demands of rural life. The renting of air space had the advantage of permitting the selection of time slots best suited to the daily routines of the target population so as to optimize the programme's reach.

Popular radio station in the Patagonian Andes

Source: G. Gutiérrez, AED Nr. 47, 1996, p. 297

One of the drawbacks of the project was the limitation of broadcasting time (ECORA did not have a transmitter of its own). As a result of growing demands, there was often a call for additional radio time, but the rigid programming schedule of the transmitter which rented out air space restricted ECORA's broadcasting time to the slots set down in the contract.

The ephemeral quality of the information conveyed in the radio programmes was also a limiting factor, although this is a limitation that lies in the nature of radio itself. Moreover, broadcasting time was insufficient to allow more in-depth development of the topics. Hence, it was necessary to complement the programmes with other media and to reinforce their content with so-called “live”, or ”in-person”, educational activities.

Working Directly in the Communities

The radio programmes served to gain the confidence of the people. This facilitated entry to the communities on the part of the field workers and paved the way for the training functions considering that the participants were already familiar with the topics and the approach.

The themes of the agricultural workshops were geared to everyday problems in the lives of the campesino families. In contrast to other projects which emphasize technical solutions to increase crop or livestock production, the ECORA approach relied on dialogue with participants to decide on the topics of discussion and to identify the specific problems faced in each community. At the same time, the issues were explored in a socio-political context (the situation of the country, the current situation of indigenous farmers, information about their legal rights and the laws pertaining to the issues in question). At the close of the workshops, proposals were made for action and mutual commitment based on the conclusions reached by the groups in their analysis of the issues.

Physical proximity was another factor that facilitated fieldwork. Regional ECORA offices had been strategically located in three targeted communities. As the team members lived in the same communities where they worked, ample possibilities existed for close contact and daily visits with the inhabitants.

In many instances the regional offices served as a venue for workshops, radio programme discussion groups, and the distribution of literacy primers and other educational materials.

Their frequent visits to the communities gave the teams many opportunities to meet with local leaders and authorities, school teachers, as well as representatives of other development organizations, and to coordinate educational activities, demonstrations and farming extension programmes.

The in-person learning functions accordingly complemented the work of other agencies and vice versa, considering that it was possible to observe the level of acceptance of the radio programmes and formats, and to determine community concerns and opinions.

The fieldworkers prepared schedules to keep the communities informed of when they would be visiting in order to organize intercommunity functions, workshops, seminars, assemblies, and education fairs.

The Education Fairs

The education fairs or festivals enjoyed considerable popularity, mobilizing entire communities to active participation in the various events. Agendas included product competitions, agricultural demonstrations, livestock exhibits, and soccer matches. Food was shared at the traditional communal lunch, known as the merienda comu nitaria so that activities were able to continue throughout the day.

Popular theatre performances were among the main attractions at the fairs. Fa-miliar characters from the radionovelas – figures with whom the people identified

– made live appearances in the performances. Theatrical events provided opportunities for direct participation on the part of the audience within the framework of discussions conducted by the radio announcers, the members of the radio teams and community workers. Community folklore groups took part in the closing events, creating an atmosphere of celebration and cultural renewal. Prizes were awarded for the performances that best retrieved the tradition of autochthonous music and dance in the region.

Besides organizing the activities and functions for the fairs, the team members put together exhibits related to the radio programmes, the literacy primers and the project’s thematic areas of focus, using relevant materials such as photographs, articles, posters, and announcements.

Each fair attracted an average of 500 visitors of all ages from the surrounding communities. Organizational complexity and the required presence of the entire team at the various activities and functions made it impracticable to schedule fairs on a monthly basis as the communities had originally requested.

A critical balance existed between the strengths and limitations of the education fairs. On the one hand, the fairs had the capacity to mobilize active community participation. Time, on the other hand, was too limited to permit optimal use of the educational resources invested over the course of a single day. Although there was a wide range of diverse activities that attracted the attention of the population, their organization demanded a substantial amount of institutional time and effort.

Plans to conduct a final evaluation of the project were never realized. Since educational functions of this nature are still in the experimental stage, their impact and efficacy remain subject to closer examination. Fairs can take on many different forms that have yet to be tried. The incorporation of new elements such as movies or videos, example given, need to be investigated. The tenuous nature of popular theatre also needs to be taken into consideration. Maintaining a stable group of players and generating new scripts on a permanent basis were tasks that exceeded the capacities of the radio team. The team was only able to lend its support in the realization of performances every three months in view of the regular demands they faced in the production of the radio programmes.

ECORA’s Approach to Education

As already mentioned in the first part of this chronical, the philosophy of Paulo Freire and Popular Education were implicit in the educational concept of ECORA. The project’s key objectives can be summarized as follows:

- to raise the consciousness of indigenous farmers and empower them to as sume an active role in the development of their communities, the organization of unions, the defence of their rights, the restoration of democracy, and the revalorization of their culture

- to mobilize the communities to improve the conditions for marketing their products by improving productivity and demanding just prices

- to promote community participation in the various activities geared to achieving these objectives

In an effort to optimize the effectiveness of the subject matter and content of the radio programmes, the ECORA team chose to use an integrated combination of available resources, mass media (radio, literacy primers), ‘mini media’ (cassettes, flip charts, practical demonstrations) and in-person functions and events (workshops, community meetings, assemblies, and education fairs).

Community education was perceived as open space for creative thinking and participation on the part of the population in a process of determining their most important productive, organizational, and cultural concerns and needs. The methods were designed with a participatory character to be flexible with respect to content and to reach large segments of the population (all members of the indigenous population including adults, women and young people, indigenous authorities, union leaders, and teachers).

The project was designed to be an experience in non-formal education. Consequently, the team avoided using models and instruments of a highly structured and “conditioning” nature that had reduced other experiences in community education to programmes of formal education (literacy training and specialized courses) that excluded other sectors of the community.

A “thematic guide” served as a curriculum, covering topics of community interest and institutional objectives. This flexible document addressed a broad range of subjects. Topics were selected to coincide with the farming calendar, for example, or with civic festivities. They concerned socio-political issues, including human rights, the Bolivian Constitution, agrarian reform laws, systems of government, the world economy, the external debt, different forms of organization, and Bolivia's social structure; as well as questions concerning production, such as costs of production, improvement of productivity, the cultivation of different varieties of potatoes, the care of seeds, crop sowing and harvesting, and cattle husbandry.

Even though the project took place during the transition period from dictatorship to democracy, self-censorship was exercised in the development of themes as well as the organization and realization of functions which the inhabitants attended in person. From a political point of view, it was a sensitive period, considering that political power was still in the hands of the dictatorship.

Nevertheless, in view of the progress made in the communities in the development of school-related skills during the two years in which the project had been in operation, the team was allowed to continue implementing their approach in spite of the prohibition.

The ECORA project approach was not based on prefabricated concepts, but rather on actual practice in a process of continuous construction, taking into account that community education is a dynamic, participatory, and constant process of community and institutional collaboration in non-formal settings. It was an ongoing effort to create awareness and to promote the organization and mobilization of collective action toward social transformation and improvement in the quality of life of the campesino families.

Community radio station in the Patagonian Andes

Source: G. Gutiérrez, AED Nr. 47, 1996, p. 301

ECORA’s Approach to Rural Development

The starting point for the programme’s focus on production was “campesino economy”. This form of production, which still prevails in the region and in the majority of the campesino communities in Bolivia, is mainly devoted to personal consumption. Based on an understanding of the logic behind campesino economy, the project aimed at increasing indigenous autonomy and control over the different stages of the production process as the basis for securing fair prices. To the extent that was reasonably possible, the project strove to improve productivity and thereby secure the food requirements and income of the farming families. Work concentrated on the development of organizational skills, the promotion of active participation, and the provision of an integrated programme of training in productive activities.

Collective action based on agreements and consensus is part of the tradition of campesino organizations. Decision-making and activities related to production are processes that involve people as individuals and the community as a whole. Training that integrates social components with those of a purely technical nature serves as a motivating factor behind work and encourages innovative practice in production.

Around the time the ECORA team initiated their efforts, there were a number of other projects active in the region which followed a technical development approach. In contrast to the ECORA project, they used an approach which aimed at increasing individual production through indiscriminate use of pesticides and fertilizers. Credits with high interest rates were granted for the purchase of agricultural machinery. Projects of this type were short-lived and left behind a devastated infrastructure, broken-down machinery, and a heavy burden of foreign indebtedness to international entities.

In Bolivia’s Altiplano the poverty index is high among campesino families. Farming and cattle raising, the only source of family income, are high-risk undertakings in this cold, arid region that lies nearly 4,000 meters above sea level. This already precarious situation is complicated by the lack of such basic services as water, elec tricity, education, and healthcare. On the other hand, the organizational potential in the region is an important asset for the Bolivian social movement. The inhabitants have a rich ancestral heritage with their own rational modes of production (although some of their advantages, such as the ecological diversity that characterized the different strata, were destroyed during the colonial period). Moreover, the Altiplano contains valuable natural resources. Potentials such as these must be taken into account when designing strategies for community education and development.

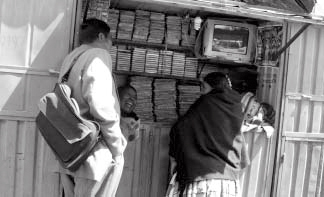

CD ”shop” in Bolivia

Source: Jorge Aliaga Murillo

Combining Media

The radio broadcasts were well-received in the region. Nevertheless, taking into account the limitations inherent in radio (unidirectionality as well as the transient and impersonal nature of radio communications), it was deemed necessary to complement the recorded broadcasts and combine them with such interactive elements as the education fairs. The following section will explore this aspect in greater detail.

Print Media – Arusquipasiwi

Educational material was produced in the form of booklets distributed under the title Arusquipasiwi, an Aymara word that served as an invitation for people to work together as a group (the literal meaning of the word is “Let’s discuss it”). Initially the booklets were issued every two weeks, but as the demand increased, the decision was made to produce them on a weekly basis.

The booklets were intended to reinforce the main points in the content of the radio programmes. As mutually complementary instruments, the radio broadcasts and the booklets both transmitted the same information and reflected on the same issues. These same issues were explored and developed in depth in fieldwork at the events and functions where people were able to participate in person. The subjects and messages conveyed in the booklets were drawn from a so-called “thematic guide” that served as a curriculum reflecting the institutional objectives which were elaborated by the team.

Subjects in the guide were organized in categories according to social and political aspects of organization, socio-cultural issues, and economic aspects of production. These main themes were subdivided into more specific topics such as community organization, civil rights, agriculture and livestock, healthcare, women in the community, and Aymara culture. Political issues were treated with caution in the face of official censorship.

The guide served as a flexible point of reference. Depending on the course of developments, it was possible to introduce new topics, or to give some topics priority while postponing others. The topics in the guide were dealt with in an integral approach. Interrelationships were explored and possibilities were examined for practical application in order to avoid viewing issues from a purely sectoral vantage.

The booklets were designed for easy use. They were printed on standard, medium-sized paper (ca. 22 cm x 15 cm), and had eight pages. Texts and illustrations followed didactic considerations. The message content was gradually expanded to include graphs and photographs. Over the lifespan of the project, a hundred issues of Arusquipasiwi were produced.

The main theme of each issue was depicted on the cover in an illustration designed to motivate interest. The first two pages were devoted to developing the main focus (e.g. agrarian reform), with the two following pages relating that focus to other aspects of campesino life (land ownership, small landholdings or “mini fundios”, or production, example given). Page 5 contained a summary of the main national news of the week. Pages 6 and 7 were reserved for illustrations, letters, and news items that had been sent in by the communities. Healthcare issues and a variety of miscellaneous topics were addressed on the final page.

Question and Answer Sheets

The booklets contained a detachable insert with questions and space for writing let ters or completing exercises around community topics. Members of the community were asked, for instance, to describe and illustrate their community’s landscape and natural resources. The insert served as a kind of supplement for feedback from the campesinos either individually or as a group. Besides serving as a means of evaluation, the responses and exercises gave community members a chance to practice their reading comprehension and writing skills. Answers were given in Spanish. Individuals without sufficient writing skills were given the opportunity to tape record oral answers.

The questions served to reinforce the main information contained in the booklets and provided an opportunity for community members to reflect on specific problems and ways to deal with them in practice. Following are a few examples of the questions:

- When was the Agrarian Reform enacted?

- What issues do small landholders have to deal with?

- Where and how can land titles be acquired under the agrarian reform law?

An effective system was devised for regular distribution of the booklets and col lection of the letters and responses. Nevertheless, the obstacle of distance made it difficult for some outlying communities to submit their responses in a timely fashion. This posed problems for the process of reviewing and organizing the responses which were included in the weekly issues, since each new issue of Arusquipasiwi contained a new set of questions. It also posed a problem for the radio team which dedicated time in their broadcasts to reviewing the letters and responses from the community. They often received reactions of disappointment from listeners who had expected to hear comments on what they had written, when actually the responses had not yet arrived at the office. There were a few cases of letters that went astray, but the system which had been devised for distributing the booklets and collecting the responses tended to function according to a unique set of dynamics.

Through a combination of methods – the radio broadcasts, the booklets with the interactive response sheets, and the work conducted directly in the community – the project helped to accelerate processes of community organization. A number of leaders in the target communities were appointed to regional positions of authority, and even went on to become representatives in the national campesino organiza tion, the Central Unica de Trabajadores Campesinos de Bolivia (CSUTCB). This organization, which was founded in 1988, carries significant political weight in the life of the nation.

Traditional dance in Bolivia

Source: Jorge Aliaga Murillo

The Closing of ECORA

The work of ECORA came to an unanticipated end with the military coup of 17 July 1980 after the new dictatorship revoked civil rights, imposed strict curfews, restricted freedom of movement outside city limits, and began to exercise tight road controls.

All social and educational activities in rural communities were suspended, at least during the initial months. A small nucleus of members from the ECORA team remained active under conditions of semi-secrecy in order to formalize the closure of the project. Winding up activities was necessary to prevent intervention that could have obliged the staff to use the radio programmes for propaganda purposes in support of the dictatorial government. Such a change in the direction of the messages would have caused confusion in the listening audience.

In the face of this situation, the contract between ERBOL and the Ministry of Education was prematurely terminated. This guaranteed the safety of the members of the staff who remained in Bolivia. ERBOL’s contract with the Ministry of Educa tion was declared formally complete, and ECORA’s operations were brought to an official close. Immediately after the project ended, a new popular education centre was established under the name “Qhana”, an Aymara word meaning “light of dawn”.

The new programme differed from ECORA in its institutional status. It was structured as an independent NGO, a non-profit, private organization. It was clear that work could not be reinitiated in the communities immediately, but only after a period of several months once political conditions improved and democratic liberties were restored.

The Qhana Centre is still active in various regions of the department. It operates its own radio station and has developed a diversified programme of activities. Qhana has replicated many of the measures and methods of the ECORA experi ence, and has built on still other features, improving or transforming them with innovations of its own.

Conclusions

Although it is normally only possible to assess the impacts of educational pro grammes in the long term, in the case of ECORA it is possible to say that significant achievements were made within the space of two and a half years:

- In terms of organization, the project contributed to the re-establishment of trade unions and indigenous organizations at every level – community, regional, and even national. It helped to capacitate indigenous officials and leaders who actively participated in the political processes leading to the reestab lishment of democracy. Some of those leaders were later elected to serve in municipal governments.

- In terms of education, two years after termination of the ECORA project, and as a result of the efforts of ECORA’s successor, Qhana, it became possible to open an indigenous training centre for leaders and agricultural advisors (Centro de Capacitación Campesina Autogestionario de Corkeamaya).

- In terms of production, measures to train campesino trainers lent continuity to the innovations and improvements in production and marketing that were initiated during the course of the ECORA project.

- In terms of communication, a tradition was established in radio broadcasting with campesino participation. Groups of young campesino radio producers and broadcasters are meanwhile even producing their own autonomous materials.

The lessons learned from the ECORA experience can be summarized as follows:

Constructing a model of community education as a collective effort without restrictions of a conceptual or methodological nature and without mechanically adopting other models was a positive factor that opened up a dynamic process of creativity and innovation. Building a multidisciplinary team with common objec tives facilitated the process of internal democratic discussion in an atmosphere of permanent dialogue.

The programme’s approach to education was enriched by a process of political and ideological analysis open to progressive currents of thought (Paulo Freire, Theology of the Liberation, Marxist ideology), although this factor was not necessarily specified in institutional documents.

A permanent process of learning how to read the signs of the time and recognize the reality of the wider political and social context as well as the reality of daily community life made it possible to integrate the knowledge of the team into the requirements and culture of the campesinos and to determine what contents were most appropriate and what messages most relevant.

Choosing a participatory rather than a directive approach was a very valid decision during the decade in question. In the authoritarian political climate that prevailed at the time, it fostered a receptive atmosphere and stimulated people to become involved in activities that were developed within their communities.

Results which held considerable promise for achieving the objectives of the project were obtained by integrating and combining radio broadcasts, printed matter, and fieldwork with instruments such as the booklets produced in the project as well as large-scale “in-person” events and smaller group activities around themes and contents dealing with social and cultural issues and subjects related to production.

The ECORA team was not entirely immune to assuming an attitude of “activism” that tended to divert their attention from other tasks. More time could have been spent in the coordination of measures with other institutions or in fostering the proc ess of networking that was beginning to emerge at the time.

More effort could have been invested in analysis, reflection and systematization. This notwithstanding, it was the high level of personal commitment on the part of the members of the team toward the transformation of Bolivian society and the improvement of living conditions for the campesinos with whom they worked which made the implementation of the ECORA project possible with all the outcomes and benefits described in this article.