Bhavita Vaishnava

“South-South-Learning and Cooperation is about developing countries working together to find solutions to common development challenges.” This helps develop a sense of ownership of the development process. Partners are mostly at par with each other, and their relationship is free from any kind of dominance and power. Bhavita Vaishnava, programme officer of the Society for Participatory Research in Asia (PRIA), one of DVV International’s oldest partners in Asia, describes the experience of stakeholders from three countries from the South, India, Bangladesh and Cambodia, who work together to promote urban local governance.

Learning through South-South Exchange: A Case on Improving Urban Governance

1. Social Accountability and Citizen Participation in the Urban Context

In a small mohalla (neighbourhood) called Satnami in Raipur, the capital of Chhattisgarh, the citizens had more than one reason to celebrate. Firstly, they had successfully been able to influence the municipal authorities in installing a new water tank in their locality as well as getting the old connection repaired. Secondly, these changes had happened within a week’s time, due to the consistent efforts of community women who prepared a resolution demanding improved water supply services.

In recent years many cities and towns across the globe are experiencing these kinds of demand driven changes or rather developments, which are notably initiated by sections of the urban poor. The analysis of this phenomenon is quite simple. It is ultimately the urban poor residing in slums, resettlement colonies, shacks, streets etc. that are most affected by the growing menace of rapid urbanization. This is due to the fact that on the one hand they lack resources, both financial and material, to deal with the nuances of urbanization, and on the other they are mostly “excluded” or barely “superficially included” in the development agendas and processes designed towards attaining urban growth.

The last couple of decades have witnessed a remarkable shift towards urbanization, where cities have fortunately or unfortunately emerged as engines of economic and commercial growth as well as centers of socio-cultural and political activities.

They have acquired a strong multi-cultural and metropolitan identity on account of their dynamic and ever expanding population base. However, the flip-side of this process of urban growth is equally stark. According to Ban Ki Moon, the Secretary General of United Nations,

“The emerging picture of the 21st century city fits many descriptions. Some are centers of rapid industrial growth and wealth creation, often accompanied by harmful waste and pollution. Others are characterized by stagnation, urban decay and rising social exclusion and intolerance. Both scenarios point to the urgent need for new, more sustainable approaches to urban development. Both argue for greener, more resilient and inclusive towns and cities that can help combat climate change and resolve age-old urban inequalities”.1

Moon’s statement clearly reiterates the paradox of urban growth and development that has struck even the best planned and organized cities around the world at some point or other. As far as the small and medium sized towns are concerned, they tell an even worse story. Especially in the developing countries, they bring to light the poor status of urban services and resources, be it water, sanitation, electricity, health and education. This is partly due to the perpetual rise in urban population, which creates immense pressure on the limited resources, and partly due to the lack of effective systems and mechanisms to manage and govern cities that face this crisis. This is particularly true for the developing countries of the global South, especially Asia, which hosts the majority of the largest cities in the world. In 2000, the region contained 227 cities with 1 million or more residents and 21 cities with 5 million or more inhabitants. Of every 10 big or large cities from the global South, more than 7 are located in Asia. Moreover, of the 100 fastest growing cities with populations of more than 1 million inhabitants in the world, 66 are in Asia.2

And this is not where it ends! The situation gets worse when this enormous growth in towns and mega-cities is not complemented by the emergence of new, or strengthening of existing support structures at the local level, especially those that are entrusted with the responsibility of managing and governing the towns and cities. At the local level they are mostly the service providing agencies such as municipalities, city/town development authorities or water supply authorities that are created by the state. In most scenarios, these institutions in themselves are not adequately armed (in terms of financial and human resources) to deal with crisis situations, nor are they clear about their roles and responsibilities, which are often overlapping. At the end of the day, the ones who have to bear the brunt of this adverse situation are the citizens, more so the poor and the marginalized.

Cambodian delegates discuss with the Mayor of Varanasi during their visit to India Source: PRIA

The world over, many countries and their governments are realizing the increasing danger posed by unplanned urban growth and trying to devise measures to effectively come out of it. Apart from the state, different actors in the civil society, academia and media are also promoting innovative mechanisms to, a) sensitize citizens about the nuances of urbanization, b) build their capacities to collectively work towards change that they can foster at the community level, and c) engage them in dialogues and demanding better services, where it is totally dependent on the authorities. The power and potential of civic engagement are not unknown to the world. Especially in the developing countries such practices are increasingly being experimented as they have exhibited some truly positive results. In some cases they are led by individual leaders/community members, and in others through a process of collective action mostly triggered by the intense need to bring about a shift in the way things are happening. Citizens in such initiatives are often supported by civil society and/or media, who play a crucial role in strengthening their voices and giving them a shape.

In fact, it is through the collaborative efforts of the different stakeholders, who, when acting as strategic partners in this process of change, are able to bring about the desired outcomes. The grassroots knowledge and energies of the communities, coupled with technical guidance and inputs of civil society, as well as the support of local authorities, are some of the vital factors that facilitate change, if converged at the right time with the right approach. The example of the Satnami mohalla quoted above (in the first paragraph), therefore brings to light the fine interplay of resources and knowledge as owned and shared by the different stakeholders. In this case, they were the affected women of Satnami, the authorities of Raipur Municipal Corporation as well as the civil society organization, PRIA (Participatory Research In Asia), who together helped in making the local governance system more accountable and responsive. To yield best results and make the process more participatory, PRIA in this initiative ensured that all the relevant stakeholders are engaged so that a shared ownership is built since the very beginning. Similarly, myriads of innovative endeavors have been undertaken in a collaborative manner by concerned stakeholders across different regions of the world, which offer a lot in terms of mutual learning and sharing.

2. Learning from Each Other (Specially South-South Learning) through the Sharing and Dissemination of Such Practices/ Interventions

Therefore, provided that there are emerging models or trends that showcase the impacts of collective action, and enough opportunities where they can be replicated and adopted, there is a need to create a link between them so that more innovative, need-based and participatory mechanisms are developed and promoted. In doing so, there are a couple of aspects that need to be kept in mind. First, it is extremely important to ensure that the principles of mutual learning and sharing are maintained so that all the stakeholders involved in the process are able to contribute their expertise and knowledge towards the common goal. Secondly, it is also crucial to realize the extent of commonalities among the different stakeholders/regions in terms of the socio-economic and political contexts, before forging an alliance among them. This is essential so that they do not feel threatened or overwhelmed by the extremes that the others bring to the table, but relate with each other in a way that the learning process becomes more meaningful for all of them.

This is what the concept of South-South learning talks about. South-South learning and cooperation is about developing countries working together to find solutions to common development challenges. This approach promotes closer technical and economic cooperation among developing countries by employing experts from the South, sharing best practices from the South, and helping to develop a sense of ownership of the development process.3 South-South cooperation is increasingly being used as a popular means to accelerate learning among the Southern countries as it provides practical and feasible solutions to some of the most impinging questions that the developing countries are facing today. It has proved to be far better than the system of North-South knowledge transfer where the Northern countries/ stakeholders usually control the process of development and the Southern partners are at the receiving end. When developing countries learn from each other by exchanging their knowledge and expertise it is bound to be a more enriching and fulfilling experience. This is so because they are mostly at par with each other and their relationship is free from any kind of dominance or power; in fact it is based on the principles of mutual learning and sharing.

In pursuance of this principle, PRIA, through the “Deepening Local Democratic Governance through Social Accountability in Asia” initiative, is trying to bring together stakeholders from three Southern countries, namely Bangladesh, Cambodia and India, to facilitate a process of mutual learning and knowledge exchange on the issues of urban governance. This initiative is being implemented with the support of United Nations Democracy Fund (UNDEF) as a resource providing agency, and PRIP Trust in Bangladesh and SILAKA in Cambodia as implementing partners. It aims to improve democratic practices in urban local governance institutions through social accountability for improving the provision of basic services to marginalized families in two Asian cities – Rajshahi in Bangladesh and Takhmao in Cambodia.

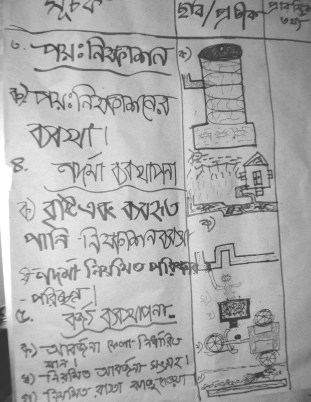

Neighbourhood Committee Members developing a pictorial monitoring chart Source: PRIA

The initiative is designed to share PRIA’s experience on improving urban local governance and accountability in Indian towns and cities with the identified cities in Bangladesh and Cambodia. It focuses on enhancing organized civic action and participation through mobilization, capacity building, campaigns and participatory monitoring in ensuring accountability. The overall objective is to build the capacities of local intermediary civil society organizations and communities through trainings, exposure visits, and mentoring for influencing national and sub-national policies on social accountability and urban governance issues.

This endeavor is therefore seen as an opportunity to promote and facilitate South-South learning, since all the three partner countries, apart from belonging to the global South, also have a shared threat and concern for the emerging development crises. They bring to the partnership their unique set of knowledge and practices that makes it a vibrant platform for exchange of ideas and meaningful deliberations. As a whole, the collaboration provides an opportunity to the partner countries to balance their limitations and weaknesses and project the best that they have to offer.

In the recent past, the governments of many developing countries have brought about a paradigm shift in their mode of governance by adopting more decentralized and participatory approaches towards development. This shift has however not been very smooth for most of these countries because it challenges notions of power and authority. Therefore, embracing the same has not been an easy task for many countries, and most of them are still struggling to cope up with the new identity.

This situation is also true, to some extent, for the three countries in this partnership. India, however, can be said to be relatively ahead of Bangladesh and Cambodia in this regard. This can be attributed to the fact that the Indian government adopted decentralization in 1991 (with the enactment of the 73rd and 74th constitutional amendment acts), which is much earlier than in the other two countries. India has also made considerable progress towards political empowerment of the marginalized groups through democratic decentralization over the years, and by virtue of this offers useful learnings to both the partner countries. In Bangladesh and Cambodia the legal frameworks for democratic decentralization are also in place with the enactment of the City Corporation Act and City Corporation Rule 2009 and the Organic Law 2008 respectively. These legal frameworks outline the roles, responsibilities and authorities of local governance institutions. However, democratic local governance is much more than a set of institutional procedures and rules. The spaces for citizen participation to co-govern the cities, to demand transparency and accountability, and to collaborate to find joint solutions are far from satisfactory.

Though “good governance” is at the heart of the Cambodian Government’s Rectangular Strategy and is highlighted as a requirement for the country to achieve poverty reduction and sustainable development, the country is characterized by weak accountability and strong corruption as well as poor enforcement of the rule of law. The highly centralized nature of the Cambodian state reduces the ability of citizens to influence issues that directly affect their lives. The distance between local protest and national government is vast4. Similarly, though Bangladesh has recently made improvements on some of its Human Development Indicators, its poor record on governance holds its potential back. Successive governments have been unresponsive to the needs of poor and marginalized communities. Instead, state power is used for personal and partisan ends, and the accountability mechanisms of the political system do not function as they should, and corruption levels remain high5.

Interestingly, in spite of the above mentioned limitations in their governance systems, all three countries possess some strong ingrained characteristics that have helped them evolve from the most adverse of situations. Be it the ever-changing nature of the Indian democracy, the Khmer Rouge and civil war in Cambodia, or the dynamics of party politics in Bangladesh, they have overcome these obstacles and exhibited their strengths in more ways than one. This partnership hence creates a greater opportunity for them to share their strengths and learn from each other.

3. South-South Learning in Practice: How Are PRIA and Partners Doing it?

In order to effectively deal with the concerns of urbanization and democratic deficit (as described at the beginning), PRIA is trying to create an enabling environment for knowledge exchange and enhancing the capacities of the engaged partners so that they can together design appropriate solutions for them. In doing so the tenets of adult and Lifelong Learning6 as well as participatory methodologies are practiced in various forms. In fact, the initiative has been designed in a way to create opportunities for interaction, discourse and negotiation wherever necessary and possible. Participatory techniques have been adopted at various stages, be it programme management or implementation of different tasks and activities. This is important as the learnings have to be contextualized before they are adopted and replicated so that they can yield the best results.

Exchange of knowledge and capacities is fostered both vertically and horizontally. In other words, cross-country sharing of knowledge by the associated civil society organizations (horizontal learning) is further disseminated in their home countries with other relevant stakeholders such as the civil society organizations (local partners, community based organizations, media, academia etc.), the community as well as with the concerned government departments in the form of vertical communication. At times these interfaces are formally incorporated in the structure of the intervention, but mostly they are allowed to emerge on their own as and when the situation demands.

In a way it can be said that learning is shared and capacities are being built at different levels through a myriad of ways. These are explained below as:

● Thematic learning among the partner organizations

First, there is the exchange of knowledge at the programme level among the partner organizations, which is related to seeking and providing technical guidance on the various components or themes of the programme. In this case they are urban governance, tools/mechanisms of social accountability (citizens’ charters, grievance redressal systems and information disclosure), citizen participation and monitoring (citizens’ reports, community based monitoring) etc. This learning helps in enhancing their capacities and prepares them to take up similar thematic interventions in the future. There are different ways in which this learning is being pursued. New and innovative means of communication are adopted to accelerate the process of learning among the partner organizations. Apart from the regular exchange of ideas and information through resource material, manuals, books, e-mails and phones, newer communication tools are being explored to make the best possible use of the available technologies. A major part of the “handholding” support is being offered “virtually” through the use of video conferencing and online meetings. This provides scope for direct interaction, where doubts and queries are raised and addressed on a regular basis, which helps in managing and implementing the initiatives at the local level.

● Learning among the different stakeholders

Secondly, learnings are also being shared among the other stakeholders both directly or indirectly. There is enough space for direct interaction and communication among different stakeholders from the three countries that has been materialized in the form of exposure visits and study tours. One of these, a study visit, was organized that brought together a range of actors including members of the civil society, media, citizens, municipal officials and elected representatives from the three countries. This visit was conducted in the two cities of Varanasi (Uttar Pradesh) and Jaipur (Rajasthan) in India, where PRIA has had considerable work experience and association with the respective municipalities and local citizens on issues of social accountability and urban governance. This visit opened up new avenues for dialogues and proved to be an effective platform to nurture and facilitate mutual learning and sharing. It was a three-way learning process where the delegates from Bangladesh and Cambodia got an opportunity to not only learn from their host country (India) but also from each other. For the Indian counterparts (officials, elected representatives, citizens etc.) too, it was an occasion to share their experiences as well as gather from the delegates how they function in their respective countries, what are the different institutions, frameworks and procedures of urban governance etc. On the other hand, knowledge is shared indirectly through the partner organizations, who learn from each other about the best practices and then transfer that piece of information to the concerned stakeholders. This sharing and capacity building happens in different ways, some of them being trainings, workshops, regular dialogues and meetings with the respective stakeholders.

The pictorial monitoring chart

Source: PRIA

● Joint learning as a group of Southern countries

In the course of implementation of this initiative, it has been realized that the learnings from the partnership go far beyond the programmatic or thematic aspects. It offers huge learnings not only in programme management and implementation but also on how such multicountry initiatives, especially among the Southern countries,can be made more effective and meaningful. What can be the dynamics and challenges of these initiatives and what are the roles and responsibilities that each partner needs to play in order to materialize the partnership? What decisions need to be taken at the local level and where do the partners need to consult each other and then arrive at a common understanding? These learnings, that can be found in many partnerships, are of utmost significance in cases of cross-country collaborations as they are of a totally different magnitude and nature. Therefore, they need to be realized, understood and put to best use by discussing them internally as well as disseminating them to others who are pursuing similar initiatives.

4. Some Results

This collaboration in South-South learning between India, Bangladesh and Cambodia, although still in the nascent stage, has already been able to exhibit some positive results. At the community level, citizens in both countries are being mobilized to participate and engage with the municipal authorities in raising demands for improved basic services. Due to the absence of organized civic action, citizens have been encouraged and supported to form neighbourhood committees. Around fifteen such committees have been formed in both countries, and they are being strengthened to identify and deal with emerging issues at the neighbourhood level. These neighbourhood committees and identified citizen leaders have also been capacitated to take up community monitoring exercises. Citizens’ Reports on WATSAN7 services have been prepared in both the cities that have revealed the unhappy state of affairs of the municipal services.

Another encouraging sign has been the positive attitude and behavior of the government officials and municipal authorities in taking this initiative seriously. In both countries they have extended their support and shown interest in collaborating with the partner organizations. Efforts towards strengthening the social accountability mechanisms in both municipalities are being pursued in full swing. In the Takhmao municipality, a task force has also been formed which is deliberating on formulating a citizens’ charter based on the services that the municipality provides to its citizens.

Apart from the citizens and municipal officials, the local media and other community based organizations have also been engaged in this partnership. Ties with media persons have led to publishing media briefs in local newspapers in Bangladesh and Cambodia that have been successful in generating awareness among the citizens about their potential role as partners in the process of change.

Notes

1 State of the World Cities 2010-11, Bridging the Urban Divide, UN-Habitat.

2 State of the Worlds Cities, 2008-09, Harmonious Cities, UN Habitat.

3 Ajay Tejasvi, “South-South Capacity Development: The way to grow?” Capacity Development Briefs, No. 20, February 2007, World Bank Institute.

4 Cited from the website http://khmerviews.com/2008/12/social-accountability-in-cambodia/

5 Cited from DFID’s report called DFID’s Programme in Bangladesh, Third Report of Session 2009–10,

http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm200910/cmselect/cmintdev/95/95i.pdf

6 Adult Education and Lifelong Learning is a continuous process with a more participative approach. It encourages dialogue and debate amongst people from the community, which is a good way of getting to know the “others” point of view. (Taken from PRIA distance education appreciation course module on “Concepts and Trends in Adult Education”)

7 Water and Sanitation.