Inclusion, diversity and exclusion: Thoughts from within Aswat – Palestinian Gay Women

Rima Abboud

Aswat

Palestine

Abstract – As this issue is about inclusion and diversity, I would like to share my humble experience of working with “Aswat – Palestinian gay women” for over a decade. The richness of the experience is difficult to summarise, thus this text aims to highlight some of the strategies utilised and challenges faced by Palestinian and Arab LGBTQI+ (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer or Questioning, Intersex+) communities.

A place of our own

Aswat (“voices” in Arabic) was founded by a group of Palestinian women who were disappointed by the circles of activism in which they were engaged. They felt that they could not be involved in these circles with all of their identities – feminist, Palestinian and lesbian. In the LGBTQI+ activism circles, for example, they felt that their sexual identity was welcomed but that their Palestinian identity had to be renounced. At the same time, within Palestinian activism groups they felt that many times the Palestinian struggle for justice and liberation prioritised justice to all Palestinian people over sexual and gender liberation struggles. Furthermore, within feminist circles, they felt that the feminist struggle was invested in gender equality and did not relate to same sex rights. Thus, the need for a space that is able to unite all oppressed identities and injustices was crucial and Aswat was established to embrace at least these three identities – Palestinian, non-conformist sexual orientations, and women.

The language and identity split

One of the main problems that Palestinian lesbians faced was the sense of being alone. The thought that one might be the only Palestinian lesbian or even the only Arab lesbian was very common. One of the reasons behind this feeling was the absence of information and literature on same sex sexuality in Arabic. In addition, the lack of sexual education at Arab schools made the Internet the only accessible and anonymous place to look for information at the time. Unfortunately, most of the “reliable” (as much as it can be) in-formation was in Hebrew or in English, thus the lack of personal stories and experiences in Arabic isolated Palestinian lesbians. Furthermore, any reference to same sex relations or love in Arabic, when found, would be full of negative ste-reotypes and derogatory terms. In addition, many Palestinian LGBTQI+ people had to live with the feeling that their sexual identity was something foreign and not authentic, as they were treated as and accused of being unauthentic – westernised, or Israelised. Both accusations detached their LGBTQI+ identities from their native Palestinian identity.

This gap between the language in which one can identify, the context in which one is living, the negative or lack of representations of LGBTQI+ Arabs, along with hegemonic prejudiced attitudes and discrimination within one’s community and outsider communities, estranged and ostracised LGBTQI+ people within their own families and communities.

My right to live, to choose, to be – Aswat's slogan, © Aswat – Palestinian Gay Women

Aswat’s projects stemmed from the needs of its community. One of the expressed needs was the desire to speak of same sex love and relationships in Arabic. This is how the Information and publication project was born. The project reclaimed the Arabic language as a language where LGBTQI+ persons could talk about their sexuality, gender identity and sexual orientation in neutral terms. This included producing new words, reclaiming old ones, and digging to find representations of same sex relations and love in Arab history that had been intentionally hidden and marginalised.

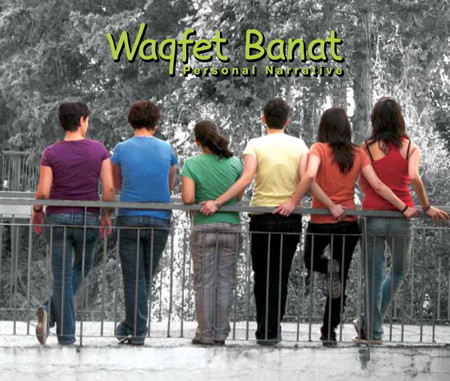

The project also worked on documenting personal stories as an attempt to write down and mobilise the oral history that was passed down by word of mouth only by women who knew other women. Documenting personal experiences and stories broke the silence and the loneliness that was found among Palestinian and Arab lesbians. This resulted over the years in a glossary of terms in Arabic, two books of personal stories of Palestinian and Arab LBGTQI+ people (see Waqfet Banat in English), a guide on sexual orientation and gender identity for school counsellors and teachers and more than 20 booklets and guides in Arabic that discuss all areas of life.1

Poster of Kooz – Aswat's 2nd Queer film festival, © Aswat – Palestinian Gay Women

To be or not to be exposed

How did Aswat manage to achieve its goals even though its founders and Aswat’s community did not believe that the only way to make a change is by disclosing one’s identity? The collective was founded so the voices of Palestinian lesbian women would be heard through it. Accordingly, all publications were presented anonymously as the main purpose was to mobilise the knowledge and pass it on to other people. The information and publication unit worked underground, and the main focus was to publish as many experiences and life stories as possible.

Aswat also published an underground diverse feminist magazine that visually looked like a mainstream magazine. Once opened, one can find rich content including information, knowledge and experiences related to diversity and inclusion.

Aswat’s magazine reached a wide range of audiences, from young school girls to adult women, who expressed their excitement and interest in contributing to the magazine. We also received the feedback that thanks to the casual look of the magazine, girls were able to take it home without arousing their parents’ suspicions. Our Arabic publications over the years helped close the gap between the isolation and the inclusion of Palestinian and Arab LGBTQI+ people with the rest of their society and communities.

Cover of the Aswat publication "Waqfet Banat” that shares personal stories of Palestinian LBTQI+ women,

© Aswat – Palestinian Gay Women

Providing the possibility to talk about one’s sexuality in one’s native language allowed Palestinian LGBTQI+ people to feel closer and more comfortable within their circles. Disseminating and exposing life stories in Arabic personified the LGBTQI+ people within their societies and refuted the dehumanising stereotypes of Palestinian LGBTQI+ people in general and within their own communities.

Education through personal narratives –

between anonymity and exposure

Another need identified by Aswat’s collective concerned the lack of education related to sexual orientations and gender identities. In response, Aswat initiated the education project in order to cater for this need. The project focused on personal stories, with the idea that a shared personal story introduces an unconventional and a complex point of view and experiences that had the power to undermine stigmas and change awareness.

The use of personal stories within our workshops had challenged Aswat’s members, since it required exposing one’s gender identity. In fact, this disclosure was debatable inside Aswat. The question: “Why should I expose my personal story in front of strangers?” was put on the table by many members. However, some members did believe in the power of a personal story and felt the change of consciousness almost immediately. Eventually, being part of the team that told their stories in our educational sessions was optional for those who believed in the strategy and felt comfortable with it. At the same time, other stories were published anonymously, allowing each contributor to decide what to disclose.

“Founding Aswat was a very bold move, where a collective of courageous women decided to initiate a change that they wanted while acknowledging their fears and concerns.”

It is worth noting that some members who were willing to share their personal stories had little hesitation regarding where and with whom to share their stories, where others did not feel very comfortable exposing their gender identities in familiar environments. To make this experience as comfortable and empowering as possible, our members would attend workshops far from their hometowns, reducing the possibilities of encountering acquaintances. Each time Aswat would take part in a session on sexual orientation and gender identities, the collective would make sure who the audience was and which team member was most comfortable taking part in that session. In doing so, Aswat’s members had ownership and agency, choosing each time when and where to expose themselves and when and where to remain anonymous. Having a choice allowed our members to go through the change we wished to achieve while catering for the needs and restrictions that we had.

Networking and integration – the more the merrier

Founding Aswat was a very bold move, where a collective of courageous women decided to initiate a change that they wanted while acknowledging their fears and concerns. Their union and shared leadership highlighted the diverse and cross-cutting issues of oppression. Realising the intersections allowed them to see the commonalities between them and other groups, including social change organisations. Since its inception, Aswat sought a space to embrace people and provide them with the umbrella they needed to start their activities. Fortunately, Aswat found that space within the feminist organisations in Haifa.

Building partnerships with other organisations allowed Aswat’s education programme to reach a wider audience. That included feminists, young activists, educators, consultants, policy makers, human rights defenders, academics, social workers, youth and others. Furthermore, Aswat worked on networking with other Arab and non-Arab groups in the region. Despite the geopolitical restrictions and dangers encountered when meeting other activists from neighbouring/hostile countries, these meetings were very good boosters for driving change. They allowed all groups to exchange ideas and experiences and think together towards solutions for specific problems, while creating opportunities for different groups from the region to work on similar goals simultaneously, such as promoting terminologies and new vocabulary in Arabic. The wider the exposure to the terminology, the higher its assimilation.

What’s next? The future

Aswat’s small community was always the well from which we drew our projects. There was so much to be done, so many needs and so few organisations to work on them. Nowadays, over a decade after its inception, there are more groups and individuals working to promote LGBTQI+ rights within Palestinian and Arab societies. Aswat continues observing and exploring the needs of the communities. For example, we initiated the first Palestinian Queer film festival in 2015. We support encouraging artists and providing our humble resources to bring their productions to life. Our experience -indicates that participatory community research is needed, and we are working this year to launch our first research based on this method. Time and time again, reality has proven for us that the knowledge is out there and our role is to facilitate collecting this knowledge and sharing it with the world, because we believe that those who suffer from discrimination and being ostracised have the capacities to inspire the solutions.

Values of justice and freedom as a compass

To conclude: It is extremely important to emphasise the inter-connectedness of local and global issues of justice and equality. Inclusion, from our perspective, is not merely limited to partnerships with groups and individuals with similar identities. Rather, we believe in promoting justice and equality in different spheres of life, where we see collaboration with groups such as groups countering militarism, feminist groups, groups fighting pornography, combating violence and bullying, and promoting indigenous people’s rights, as feasible possibilities for collaboration. We perceive values of justice and freedom as inseparable from our work and from our partners. We believe that one cannot promote LGBTQI+ issues without taking a stance against oppression, occupation, and discrimination of other groups and peoples or by being complicit in orders that perpetuate oppressive and discriminative mechanisms. Thus, we believe that inclusion and diversity are based on values and practices that our partners hold towards their communities and the world. Raising awareness about sexual identities and orientations in our communities means that we are also responsible for raising awareness around the world on issues of injustice and inequality which affect our suffering and seclusion.

About the author

Rima Abboud is a feminist Palestinian lesbian activist and human rights defender, an educator specialising in issues of gender and non-conformist sexuality, a graphic designer, and recently a mother to twins who are now two years old. Ms. Abboud has led Aswat’s Information and publication project for a decade.

Contact

rima.abboud@gmail.com

https://www.facebook.com/aswat.voices