Community learning in the no bondage society

Rika Yorozu

Rika Yorozu

UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning

Germany

Abstract – Local community development is important, both as a purpose and content of Youth and Adult Education, and as a means of increasing par ticipation. Drawing on commitments and recommendations concerning community learning from international events organised by the UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning, the ar ticle concludes with four areas of action to reinvigorate learning in and through community-based learning centres: government commitment, diversification of income, professional development and networking.

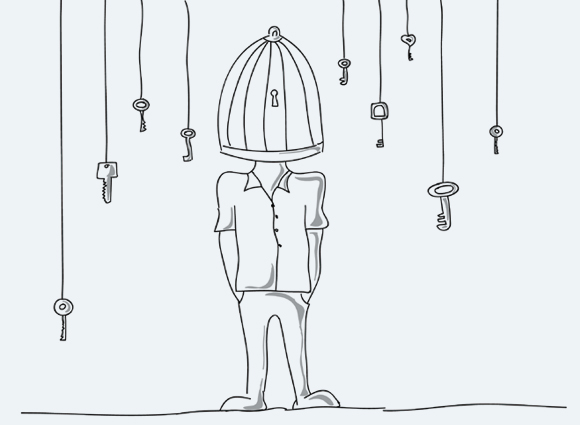

While the way communities function is changing across the world, the role of community in Lifelong Learning remains as significant as ever. The question is whether learning through community is adapting to changing learning demands and lifestyles. In other words, are the various forms of community learning following the principles of the learning organisation, where people continually expand their capacity to create the results they truly desire, where new and expansive patterns of thinking are nur tured, where collective aspiration is set free, and where people are continually learning to see the whole together.

Some say that traditional communal ties are weakening. This is symbolised by muen-shakai, a new term in Japan meaning ‘no bondage society’. An example is that the late discovery of an elderly person’s solitary death is no longer newswor thy. On the other hand, the Arab Spring showed how Arabic-speaking youth were able to bond across borders using online and offline social networks. The new mobile technology and common language supported youth in Arab States to organise their actions, and communicate their messages and threats from authorities.

Let us start our journey by looking at the commitments and recommendations concerning community learning that has emerged from the UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning (UIL) over the last few years. The Institute’s mission is to promote the recognition of and create the conditions for the exercise of the right to education and learning through Lifelong Learning with a focus on adult and continuing education, literacy and non-formal basic education.

It all started in 1976

Community development as a purpose and content of Adult Education and as a means for increasing par ticipation in Adult Education was articulated in the UNESCO Recommendation on the Development of Adult Education (1976). This signified the global community’s recognition of the community’s role in learning and education. As the only official interna tional norm on Adult Education, it emphasises that Adult Education should benefit the entire community and give special priority to the learning needs of disadvantaged groups.

The role of the community element in expanding access to Lifelong Learning is reemphasised in outcome documents of conferences organised by the UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning in recent years. The other key elements are family, school and the workplace.

The Belém Framework for Action (subtitled “Harnessing the power and potential of adult learning and education for a viable future”) adopted at the Sixth International Conference on Adult Education (CONFINTEA VI) in 2009 included community organisations as partners to promote Adult Education alongside the “public authorities at all administrative levels, civil society organisations, social partners, the private sector … adult learners’ and educators’ organisations”. Countries and organisations participating in this conference made a commitment to “creating multi-purpose community learning spaces and centres”. The Asia-Pacific Programme for Education for All (APPEAL) at the UNESCO Regional Of fice for Education in Bangkok has been developing capacities for planning and managing such centres by government and civil society organisations. Since the late 1980s this programme has fostered community learning centres in more than 24 countries in the region with the financial support provided by the government of Japan and other countries and agencies. The work includes long-term capacity devel- opment and South-South cooperation through pilot activities, development of tools (manuals, good practice case studies) and connecting stakeholders. The result is subregional collaboration initiated by the countries.

Learning from each other

The experiences of community learning centres in Asia are now spreading to other regions. As a result of international cooperation and exchanges supported by UNESCO, some Arab States and African countries have begun piloting community learning centres. Before the introduction of these centres, the most typical venues for adult literacy in developing countries were public spaces (i.e., schools) and private places such as a teacher’s home. Having a more permanent space for community members to come together for individual and group learning and community development is an ef fective way to build a learning environment at community level. [In this issue you will find several examples of such community learning centres, Ed.]. Nigeria’s National Commission for Mass Literacy, Adult and Non-Formal Education (NMEC) plans to set up model literacy centres inspired by Indonesia’s experiences with community learning centres. Several Arab States, such as Egypt, Morocco, Jordan, Lebanon and Palestine are upgrading their community learning centres following successful pilot phases.

“As a result of international cooperation and exchanges suppor ted by UNESCO, some Arab States and African countries have begun piloting community learning centres.”

The Second Global Report on Adult Learning and Education (GRALE) repor ts on experiences of creating community learning spaces from the Philippines, Slovenia, Mongolia, Brazil and Finland. These cases indicate the benefits of providing learning oppor tunities and information/guidance within walking distance of learners’ homes. The UNESCO Ef fective Literacy Practices Database (LitBase) provides many fur ther examples of successful community learning centres. UNESCO has also set up an open platform to encourage networking and exchange among community learning centres in twenty Asia-Pacific countries.

Why community matters

Concerned with slow progress in reducing youth illiteracy, especially the persistent gender gap in literacy, UIL has initiated activities focusing on marginalised young people with little or no experience of formal schooling. Good practice examples of engaging young men and women in community learning centres are featured in a briefing note by UIL, Community Matters: Fulfilling Learning Potentials for Young Men and Women. Experiences from Bangladesh, Indonesia, Japan, Mongolia, Thailand, and UK are mainly drawn from presentations and discussions at the International Policy Forum on Literacy and Life Skills Education for Vulnerable Youth through Community Learning Centres in 2013. The main recommendation of this brief is to review policies and guidelines on community learning centres in order to facilitate the involvement of young people in community education, and to provide training oppor tunities for them to successfully participate in community education and development. It also recommended research on the impact of communit y learning centres to have strong evidence to recommend government suppor t for these centres.

Another area of UIL’s work is to build learning environments for all at local governance level through the establishment of the Global Network of Learning Cities. The Beijing Declaration on Building Learning Cities adopted at the first International Conference on Learning Cities in 2013 devotes a full section to revitalising learning in families and local communities:

- establishing community-based learning spaces and providing resources for learning in families and communities;

- ensuring, through consultation, that community education and learning programmes respond to the needs of all citizens;

- motivating people to participate in family and community learning, giving special attention to vulnerable and disadvantaged groups, such as families in need, migrants, people with disabilities, minorities and third-age learners; and

- recognising community history and culture, and indigenous ways of knowing and learning as unique and precious resources.

The corresponding Key Features of Learning Cities indicate seven possible measures to support community learning. These features, which were piloted in several cities in 2013, are meant as a reference point for planning, implementing and evaluating actions to build learning communities.

In the medium-term strategy of the UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning (2014–2021), the Institute plans to establish par tnerships with selected regional and national institutions to suppor t the establishment of community learning centres as one of the key deliverers of Youth and Adult Education.

“There is a broad consensus that community education has a significant role to play in building a learning society.”

The to do list

There is a broad consensus that community education has a significant role to play in building a learning society. What then needs to be done? Let us look at four main lines of action – government commitment, diversification of income, professional development and networking – which may enhance the role of community education.

Government commitment

Support is needed in a number of areas, most importantly institutionalisation of community-based learning centres by giving them legal status or official recognition. This helps in replicating the CLC model nationwide and in ensuring that centres receive funding directly from local and international partners. For this to happen, the centres’ mandate and management framework needs to be included in national education and development policies. Such institutionalisation should not lead to over-standardisation. Flexibility in delivery of community education should be kept to address different contexts. In Thailand for example, government supports different types of CLCs: “the highland type of CLCs, the lowland type, CLCs in particular areas and CLCs that represent sub-district NFE Centres”.

Diversification of income

National and local government schemes to finance the activities of community-based learning centres is a basic condition to enhance the sustainability of these centres. Some form of income-generating activities by the centres themselves helps to supplement the income from government and/or external donor funding. Income can be generated by charging for community ser vices, such as rooms to rent, catering facilities for weddings, and operating cooperative shops. Income generated in such ways should be used to finance diverse and affordable learning and development activities for local communities.

Professional development

Ultimately, the people who work at community-based learning centres determine their success or failure. However, the status of CLC staf f in developing countries, such as adult literacy facilitators, tends to be low. Many have low educational qualifications and receive only token remuneration for their services (UIL 2013). In countries where the educators or facilitators of community education receive status and salary equivalent to primary school teachers, the activities coordinated by them tend to respond better to the learning demands of community members and thus attract greater participation. Motivated professionals supported by dedicated community leaders enjoy greater functional autonomy and deliver higher-quality services.

Networking

Linked to the previous point, there is a need to strengthen networking and experience sharing among communit y learning centres, both locally and internationally. At local level, associations of CLCs, such as those active in Indonesia and Nepal, or clusters of CLCs, as in Bangladesh, foster mutual learning and inspire community leaders and professionals to improve their work. Information and communication technology has great potential to suppor t networking activities. Access to such technology in CLCs, especially for young people, can greatly enhance par ticipation levels and contribute to community education and development. At international level, UNESCO has established an online platform for community learning centres in Asia-Pacific countries. As more centres par ticipate, this platform is likely to provide a highly valuable resource for inter-cultural learning.

“A vibrant and warm learning environment built around community learning centres can strengthen the creation and reconnection of bonds among members of a local community and across communities.”

The humanistic vision

Ar ticle 6 of the World Declaration on Education for All adopted in Jomtien in 1990 sums up a humanistic vision of the linkages between learning, community and family:

“Learning does not take place in isolation. Societies, therefore, must ensure that all learners receive the nutrition, health care, and general physical and emotional support they need in order to participate actively in and benefit from their education. Knowledge and skills that will enhance the learning environment of children should be integrated into community learning programmes for adults. The education of children and their parents or other caretakers is mutually suppor tive and this interaction should be used to create, for all, a learning environment of vibrancy and warmth.” (UNESCO 1990: 6–7)

While the current focus of the global education debate is on reviewing the progress made in reaching the Dakar Education for All goals and preparing for the post-2015 global education agenda, I find that the humanistic vision of Jomtien is still valid and relevant. A vibrant and warm learning environment built around community learning centres can strengthen the creation and reconnection of bonds among members of a local community and across communities.

References

Iwasa, T. (2010): It is time for Japanese Kominkan to flower again. In: Adult Education and Development, Issue 74, 65–74. Available at http://bit.ly/1i60TOl

Makino, A. (2013): Changing grassroots communities and lifelong learning in Japan. In: Comparative Education, Vol. 49, No. 1, 42–56. Available at http://bit.ly/1i61jo3

Sawano, Y. (2012): Lifelong Learning to Revitalize Community Case Studies of Citizens in Learning Initiatives in Japan. In: the Second International Handbook of Lifelong Learning. Dordrecht: Springer Science + Business Media. Available at http://bit.ly/1kN84KZ

Smith, M. K. (2001): Peter Senge and the learning organization. In: the encyclopaedia of informal education. Available at http://bit.ly/1jV0zl5

Suwanpitak, S. (2013): CLC as a Vehicle for Promoting Lifelong Learning in Thailand [PowerPoint Presentation]. Available at http://bit.ly/1pI6OR6

UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning (UIL) (2010): CONFINTEA VI: Belém Framework for Action: Harnessing the power and potential of adult learning and education for a viable future. Hamburg: UIL. Available at http://bit.ly/1qF99Kj

UIL (2013a): 2nd Global Report on Adult Learning and Education: Rethinking Literacy. Hamburg: UIL. Available at http://bit.ly/1n8JW8X

UIL (2013b): Quality matters: improving the status of literacy teaching personnel. UIL Policy Brief 1. Hamburg: UIL. Available at http://bit.ly/UyLZv4

UIL (2014a): Beijing Declaration on Building Learning Cities. Hamburg: UIL. Available at http://bit.ly/TRCAOF

UIL (2014b): Community Matters: Fulfilling Learning Potentials for Young Men and Women. UIL Policy Brief 4. Hamburg: UIL. Available at http://bit.ly/1kuMsU7

UIL (2014c): Key Features of Learning Cities. Hamburg: UIL. Available at http://bit.ly/1sb40y6

UNESCO (1976): Recommendation on the Development of Adult Education. [HTML] Available at http://bit.ly/SxuObM

UNESCO (1990): World Declaration on Education for All and Framework for Action to Meet Basic Learning Needs. Available at http://bit.ly/1p0Ejus

UNESCO (2013): Community Learning Centres: Asia-Pacific Regional Conference Report 2013 – National Qualifications Frameworks for Lifelong Learning and Skills Development. Bangkok: UNESCO Bangkok. Available at http://bit.ly/1mWVBaC

Further reading

Community Learning Centres in Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/clcnet

Community Learning Centres Network: http://www.clcap.net/

UNESCO APPEAL Resources: http://bit.ly/1pRADN5

UNESCO Effective Literacy Practices Database (LitBase): http://bit.ly/1i64bkN

About the Author

Rika Yorozu is Programme Specialist for Literacy and Basic Skills at the UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning (UIL). She provides support to developing and middleincome countries in Asia and Africa. Before joining UIL, she promoted regional collaboration in adult literacy programmes at the Asia-Pacific Cultural Centre for UNESCO (ACCU Tokyo) and at the UNESCO Regional Bureau for Education in Bangkok.

Contact

UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning (UIL)

Feldbrunnenstrasse 58

20148 Hamburg

Germany

r.yorozu@unesco.org

http://uil.unesco.org