How to empower a community from a distance

Priti Sharma

Priti Sharma

PRIA International Academy

India

Abstract – Communities can be empowered through distance education. This is what the PRIA International Academy (PIA) is doing in India. Through educational programmes, a wide array of individuals and organisations are helped in their ef for ts to bring about social change. The learners are practitioners, academics, trade union leaders, community leaders, activists, students and others. They all use the distance courses to improve their theory and field practice in their efforts towards the empowerment of communities that they engage and work with.

In 1978 an informal network of adult educators, inspired by Paulo Friere, constituted a forum for promoting participatory research in Asia. PRIA’s (Par ticipator y Research in Asia) inception is linked to this informal network. As a non-profit voluntary development organisation based in New Delhi, India, PRIA has been promoting people-centred development initiatives within the perspectives of participatory research.

PRIA’s work is built on the premise “Knowledge is Power”. This premise has been an instrumental starting point for more than three decades. PRIA has firmly believed in the principles and tenets of Adult Education. People have the knowledge and the power to change their lives if given the proper tools to analyse their situation and find solutions for change. PRIA has always supported the empowerment of communities, especially the poor and the marginalised, through its efforts in research, training and capacity building.

Building capacity

Capacity building has been an integral par t of PRIA’s work from the star t. These ef for ts have been aimed at citizens, government organisations, donors and community based organisations through structured trainings and workshops, ongoing field support, hand-holding and exposure visits, etc.

PRIA’s capacity building ef for ts are widely acknowledged throughout the development sector in India and globally. However, with the demand for additional training programmes on varied thematic issues, it became clear that the face to face mode of education (trainings) was unable to meet the needs of the sector, given the volume of people that were being catered to.

Learning at a distance

It is with this background that the PRIA International Academy was established in 2005. The primary objective of this academic wing was to collate, synthesize, build upon, repackage and disseminate PRIA's vast body of knowledge and learning. This existing knowledge was in the form of research studies, field-based programmes, trainings modules, workshop and seminar reports, papers, publications, books, journals, audio-visuals, films, etc. They covered a wide range of development issues that PRIA had worked on in the field, either directly or in collaboration with its partner organisations.

The primary targets for the educational programme include:

- the development worker;

- the individual in mid-career;

- the practitioner with strong field experience and informal learning;

- the adult learners who want to develop an academic base to complement practical experience and reach out to the larger communities with a strong conceptual and theoretical framework, tempered by practitioner experience – their own and those of other learners, course facilitators and guest faculty.

To empower a community

The question that may be asked at this point was how a formal, structured distance learning programme was going to benefit communities, especially since they were not the direct beneficiaries of the same. Even though these courses do have community empowerment as their final outcome, they were designed to build on the skills and knowledge of the learner involved with various communities.

The Academy – as all other divisions of PRIA – works on the principles of Adult Education. It strongly advocates that people have a natural inclination toward learning which will flourish if nurturing and encouraging environments are provided. The courses that PRIA currently of fers promote an empowerment oriented approach to learning.

All courses are designed in such a manner that a learner working on the issue would find it very useful. The discussion forum available to participating learners is another opportunity to learn from each other’s experiences. They can share the experiences in the field, ask questions and learn from others who have been working on similar issues. The knowledge gathered this way is used in the field for better implementation of specific projects. The discussion forum sharing also facilitates taking up of such cases/practices in other areas by the practitioners.

Lots of opportunities

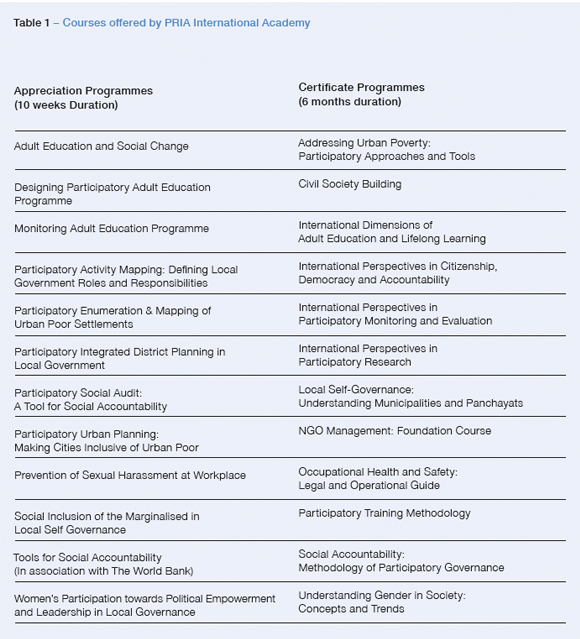

The Academy offers certificate and appreciation programmes through a distance learning model. These programmes run for 6 months and 10 weeks respectively. Some of the courses offered include Participatory Monitoring and Evaluation, Par ticipatory Research, Social Accountability, Social Audit and Prevention of Sexual Harassment at the Workplace. They all provide learning that supports the efforts of empowering the community. The courses offered by the Academy cover a whole spectrum of issues with a focus on the empowerment of the communities (Table 1).

The appreciation course on social audit focuses on the importance of participation between communities and institutions of local self-governance in undertaking social audit exercises. A social audit builds a long-term positive environment in a community and helps to develop a sense of ownership amongst various stakeholders. It is useful in providing an assessment of the impact of a financial organisation’s objectives through systematic and regular monitoring of its performance based on the views of its stakeholders.

Girls, education and harassment

The six-month course on participatory research as a tool for social change was used ef fectively in one of PRIA’s field sites. Things learned from the course were used by a partner institute to engage young girls belonging to a Scheduled Castes community in order to conduct research within their villages on why they were denied access to even basic education. Scheduled Castes, or Dalits, are also known as untouchables and are the lowest in the hierarchy of the social structure in India.

The findings of the research were used to initiate discussions on the rights of girls to education, create awareness on the issue and bring about social change in this direction. The research conducted by these young girls served two purposes. Firstly, it generated knowledge on the existing practices of societal discrimination against Scheduled Castes and secondly the knowledge so generated motivated the girls to challenge these existing practices and bring about change for themselves.

Similarly, practitioners working on issues related to gender discrimination in society and the prevalence of sexual harassment at the workplace attended some distance courses on the subject. They now use what they have learnt to reach out to the communities they work in. Both these examples show that tools and methods of participatory research are used not only to create and increase awareness, but also to enable the community to use what has been learned for positive change.

One of the appreciation courses deals with women’s participation towards political empowerment and leadership in local governance. This course, based on a project run by PRIA, has enabled practitioners to build up a cadre of women in their community to play the role of citizen leaders and also contest local elections for representation in local governance. Using the tool of distance education, community facilitators have been able to reach out to hundreds of women at local level and influence them to participate in the leadership and governance of their communities.

To find the informal settlements

Another appreciation course on participatory enumeration and mapping of urban poor settlements promotes participation from the communities concerned. This course has helped learners obtain tools for involving communities in urban settings in the mapping of their settlements, using GPS (Global Positioning System) and other methods of enumeration. The information obtained has then been presented to the officials of the municipality concerned. This has helped establish the existence of informal settlements. These are settlements not present on the city map, even though they have existed for more than 15 years. Once on the map, residents have been able to demand their rights to basic services of water, electricity and other amenities. This process not only created awareness within the community regarding their rights as citizens, it also helped develop cohesion within the community. It created a new cadre of young citizen leaders, as well as developed skills on negotiating with officials to improve quality of life for all.

The process of online teaching is firmly based on the principles of adult learning, wherein the instructors are facilitators in the learning process. The process is designed to encourage discussion and the sharing of experiences between the learners. This helps them build on their existing body of knowledge. The international composition of the online learners brings about a wide range of experiences, enabling the creation of new knowledge that can be used by all, including the facilitators. These experiences can also be shared with a larger group through newsletters and magazines. While such writing may not always be academic in content it ser ves the purpose of reaching out to a large number of practitioners and other people.

As good a tool as distance education is, there are challenges when promoting distance education for community engagement and empowerment. Let’s look at some of them.

Challenges

Language: As the courses are of fered in English, the number of people that can be reached becomes a limitation. Most students come from India, Asia and Africa, and English is not their first language. As a result, learners are sometimes unable to share their experiences as they cannot articulate their learning.

Connectivity: Since the courses are online, many learners in remote areas are not able to access the information on time. This sometimes hinders the timely sharing of information, experiences, challenges faced by them in the field, as well as timely completion of the course requisites.

Time zone: Responses are delayed because of different time zones that learners are in.

Academic style of writing of the course content: The courses are written in an academic style to ensure quality of the courses offered and also for accreditation purposes. Learners have reported that they sometimes find this style difficult to understand. Efforts are now underway to address this issue.

Where it all leads

Over the years, and despite many challenges, the Academy has evolved as a provider of education in bringing about social change and community empowerment. Feedback from learners has changed the structure of course teaching, deliver y mechanisms and presentations in order to accommodate the different levels of learners in completing a course. The system now has a flexible course period accommodating the learner. The system, with low fees, has also made it possible for many to par ticipate in the programmes. The course structure allows learners to interact with the guest faculty who could be based anywhere in the world to share their experience and expertise on the subject matter.

References

Dale, P. & Kaul, N. (2012): Participator y strategies for Adult Education and social inclusion. In: Adult Education and Development 78/2012. Bonn: DV V International. Available at http://bit.ly/1k8K6v9

PRIA (2002): Historical journey of PRIA. New Delhi: PRIA.

PRIA (2014, April 25): Module 1: Understanding Adult Education. Adult Education and social change. New Delhi: PRIA.

About the Author

Priti Sharma has around 18 years of work experience in the development sector and has worked on issues related to local governance, civil society engagement, sexual harassment at the workplace and human resource management, among others. In the past, she has worked on these issues in different capacities, such as researcher, trainer and coordinator. Currently, she is involved with PRIA International Academy (PIA) as Senior Programme Manager.

Contact

PRIA

42, Tughlakabad Institutional Area

New Delhi – 110062

India

piall@pria.org

www.pria.org