Ricarda Motschilnig

One of the major obstacles for Adult Education when trying to secure a position on the priority list for public commitment and budgeting is the scarcity of hard facts that demonstrate the positive impact it has for the learners and the society they live in. That is why DVV International and the German Institute for Adult Education (DIE) initiated a research project under the title of “Benefits of Lifelong Learing (BeLL)“, financed by the European Union, with the aim of comparing learning efforts with the benefits achieved by adult learning for the well-being both of learners and communities. The study demonstrates palpable results of adult learning in a number of fields such as health, civic engagement, parenting, poverty reduction, well-being and happiness. Ricarda Motschilnig who specialized in the field of Intercultural Education and Community Education with adults, summarizes the findings. The full study will shortly be available online: Motschilnig, R./Thöne-Geyer, B./Kil, M. (2012) What Adult Education is for? The Wider Benefits of Adult Learning – An approach and it’s outcome, texte-online, DIE, DVVinternational, EAEA, Bonn, in press.

Wider Benefits of Adult Education – An Inventory of Existing Studies and Research

Over the last few years, political as well as scientific debates have stressed the growing importance of Adult Education. There prevails a consensus that Adult Education plays a significant role in promoting personal, social and economic well-being, which has also long been recognized by DVV International. There is a deep rooted belief that adult learning has the potential to create personal, economic and social value.

However until recently, much of the evidence on the benefits of adult learning was anecdotal, even aspirational. While there were serious studies of the benefits of schooling, further and higher education, relatively little attention had been paid to the benefits of learning in adult life. Furthermore, there was a well-established tradition of research on the economic returns of education but the idea of social and personal returns from learning was relatively under-researched. The lack of evidence on the benefits of Adult Education, especially those not linked directly to the labour market, is a major obstacle in gaining recognition for a sustainable framework and reliable state support for the sector.

This paper argues that Adult Education affects people’s lives in ways that go far beyond what can be measured by labour market earnings and economic growth. Important as they are, the wider benefits of adult learning are neither currently well understood nor systematically measured.

Evidence of the “Wider Benefits of Adult Education”

There is now a growing body of research in the area of wider benefits of adult learning and this article looks individually at the particular “benefit-themes”, including economic benefits, health, civic engagement and social cohesion, attitude change, (educational) progression, crime, parenting, poverty reduction and well-being. Key studies were found in Western, Central- and Northern-Europe (United Kingdom, Germany, Austria, Finland and Denmark), Canada and Australia, while further studies were conducted by OECD, CERI and UNESCO.

Economic Benefits of Adult Education

Adult learning can improve employability and income, which is a key pathway to realizing a range of other benefits. For example it enables people to some extent, to choose and shape the context in which they live and work and even increase their social status. The existing studies focus on the economic return to work-based training and to employer provided training, which indicates that this can have significant impact on earning and the employment situation of individuals, for example reduce the risk of unemployment.

- In the UK (Feinstein et al., 2004) it was found that that work-related training gives a clear wage gain of 5-10 percent.

- A study in Austria (OEIB, 2008) among participants in vocational training found that those who attended a course earned 11 percent more than they did before attending the course.

- Also the German Expert Commission on the Financing of Lifelong Learning (Timmermann, 2010) referred to significant income returns for training participants aged 20 to 44 years in Germany.

In particular, individuals less likely to be in employment (migrants, women from ethnic minorities, etc.) may benefit economically from their participation in Adult Education.

In regard to employment opportunities it was found that adult and further learning significantly reduces the risk of unemployment (Sabates, 2007) Also Jerkins et al. (2003 in Ferrer and Riddel, 2010) analyzed the impact of education on employment and wages and their findings revealed that episodes of Adult Education, in particular vocational training, have positive effects on employment (but limited effects on wages).

Health

Empirical evidence has found that adult learning can have both transforming and sustaining effect on health. Transforming effects are when adult learning changes health behaviour (for instance from smoking to non-smoking) while sustaining effects are when health behaviour is maintained, for example the likelihood of remaining a non-smoker.

Therefore people attending Adult Education courses are more likely to have healthy lifestyles, and there is a body of literature which describes adult learning and its relation to mental health. Also, intergenerational effects of educated parents on their health of their children are very relevant.

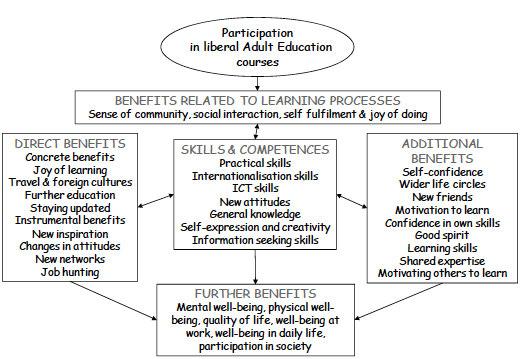

In Finland, Manninen (2008) conducted research with the aim to analyze the wider benefits of participation in liberal Adult Education and developed a conceptual model of the wider benefits of learning based on five categories (see figure below) identifying 35 main themes.

Manninen (2010:8) “Conceptual model of wider benefits of learning”

Manninen’s results showed that liberal Adult Education in Finland brings positive outcomes to individual’s lives as well as benefits – at least in a long run – wider communities and society in general. It was estimated that approximately 900,000 people have been able to develop their skills and competencies and well-being. In this Finnish study (Manninen, 2010), 28 percent of the respondents cited mental well-being as an outcome of learning and 13.2 percent mentioned improved physical health.

Civic and Social Engagement

Many countries share a concern about declining levels of voter participation and about the state of civic participation. It is possible that adult learning might inspire a change in attitude which in turn brings about a change in behaviour. Several studies (OECD 2007; Desjardins and Schuller, 2006; Field, 2009; Preston and Feinstein, 2004; Bynner and Hammond, 2004, etc.) show that learning can promote social cohesion and strengthen citizenship. Adult learning may support the development of shared norms, greater trust towards other individuals and the government and more civic co-operation.

The OECD (2007) suggests that adult learning experiences can foster civic and social engagement in various ways:

- By shaping what people know – the content of education provides knowledge that facilitates CSE

- By developing competencies that help people apply, contribute and develop their knowledge in CSE

- By cultivating values, attitudes, beliefs and motivations to encourage CSE

Attitude Change

An individual who participated in adult learning may differ from one who does not in terms of prior attitude. It was found (Feinstein et al, 2003) that adult learning is associated with more “open-minded” perspectives on race and authority, greater understanding of people from different backgrounds, challenging previously held beliefs and with a sustaining effect on non-extremist views. Especially academic oriented courses are most suited for opening minds and generally link adult learning to increased racial tolerance, a reduction in political cynicism and a higher inclination towards democratic attitudes. The most obvious effect on environmental concern and awareness is through taking vocational courses (Preston and Feinstein, 2005).

(Educational) Progression

Progression into other learning is an important outcome of Adult Education. There is clear evidence that (successful) engagement in learning provides an incentive for further learning. Manninen (2010) found that 93 percent of course participants said that their participation has motivated them to learn more.

Furthermore, learners described their progress by referring to the real life activities they could now do in a wide variety of life contexts (everyday and leisure practice, work and community and educational practice). Self-confidence, finding voice and opening up to learning were identified by almost all learners and seemed central to their perspective on learning. These outcomes provided improvement in the quality of their lives and became part of their learner identity.

Crime

The Centre for Research on the Wider Benefits of Learning claims that people with no qualifications are more likely to be persistent offenders (Feinstein et al, 2008). It is stated that success or failure in learning is strongly related to propensity to commit crime. Schuller (2009) believes that general education and training reduces the risks of people engaging in criminal activity and re-offending. In the way that Adult Education promotes personal soft skills, such as self-regulation, behavioural management, and social and communication skills, those with such traits are, for example less likely to commit crimes. However we need better and more analysis of the benefits of Lifelong Learning in relation to crime and imprisonment.

Intergenerational Effects, Parenting

The literature reveals that educational attainment in one generation has positive effects in the next generation (Wolfe and Haveman, 2002). Studies agree that learners become better parents, in that they are more patient, understanding and better at listening to and supporting their children by engaging their children more, serving as role model learners and becoming more involved parents. The findings of Centre for the Research of the Wider benefits of Learning show that the children of parents with no qualifications are already up to a year behind the sons and daughters of graduates by the age of three (Feinstein et al. 2008).

Poverty Reduction

Although inadequately understood, Adult Education has been cited as a key in reducing poverty levels around the world (UNESO-UIL, 2009 in EAEA, 2010) as it has the capacity to positively affect many dimensions of poverty. Results show that Adult Education has a role to play in nurturing the skills and knowledge necessary to both reducing the risk of poverty but also for providing the capacity to withstand poverty-inducing pressures.

EAEA (2010) underlines the empowering role that Adult Education can have in times of crisis, providing a stable community, a chance for reorientation, a safe place and social recognition. Also, the UK the Inquiry into the Future of Lifelong Learning (IFLL) (Sabates, 2008) concludes that participating in adult learning can help substantially to reduce poverty through enhancing employment prospects, improving health levels of poor people and giving better chances of acquiring the tools needed to run their own lives. Therefore it should be a part of any approach to reducing poverty, as multiple initiatives are needed to lift people out of poverty.

Well-being and Happiness

Now a considerable body of recent research has explored the relationship between adult learning and well-being. For example the Bertelsmann Foundation (Schleiter, 2008) conducted a survey asking for their subjective opinion concerning the role of Lifelong Learning in fostering happiness and well-being. In all 35 percent of the participants in this survey saw a strong correlation between Lifelong Learning with happiness and well-being.

The Centre for Research on the Wider Benefits of Learning (Preston and Feinstein, 2004) provides some evidence of effects on subjective well-being and links adult learning to increases in self-confidence and self-worth. Direct effects of adult learning relevant to well-being are, for instance, self-efficacy, confidence or the ability to create support networks. In one study (Field, 2009) four-fifths of learners aged 51- 70 reported a positive impact on areas such as confidence, life satisfaction and their capacity to cope. Feinstein et al.’s longitudinal analysis found that learners were more likely to report gains in self-efficacy and sense of agency than non-learners. (Feinstein et al, 2003).

Main Gaps and Shortcomings

Reviewing the literature and research on the benefits of adult learning, ten key shortcomings where identified:

- Gaps in Knowledge Base: First of all, only a few studies focus on adult learning and its learning experiences that matter for wider benefits, which means that there are substantial gaps in our knowledge base on the potential impacts adult learning.

- Focus on attainment in formal education There is a focus of empirical evidence on formal educational attainment, without considering non- and informal learning. Most studies focus on the number of years/months or level of educational attainment and formal qualifications as an indicator of output, mainly because these kinds of data are cheaply and easily collectable.

- Focus on human capital and economic outcomes So far, the human capital theory has linked education to economic outcome, and still the emphasis very often lies on the economic benefits of learning.

- Focus on vocational training Moreover, data is primarily available for vocational training. Little research and specific evidence exits on general and leisure adult learning. There is no empirical evidence exactly how and which types and approaches of learning interventions are most effective and generate higher benefits for adults.

- Education decisions One of the main research questions is still why adults engage in (or refrain from) education, and if they engage, in what type of Adult Education they engage.

- Selection Bias Moreover, for each participant we can never know what outcomes that individual would have experienced had s/he not participated. Although many studies have used comparison groups, simple comparisons of non/participants are likely to be subject to selection bias and do not provide reliable estimates of benefits.

- Verifiability of cause It is not always possible to conclude that learning is the primary cause of benefits. We have to be aware that the data does not prove that adult learning necessarily caused these changes and benefits and does not show us in which order or sequence events occurred. There might be unobserved other factors in life from which the benefit may arise.

- Representation The results of the aforementioned studies have to be handled with care, as they may not be representative of adult learning across and between the countries. Much of the recent research has been carried out in Britain, so there is a strong case for looking closely at other states and societies. It was found that we know little about the benefits of adult learning, for example, in Eastern-European and Mediterranean nations.

- Transferability Another issue is the transferability of results between regions as well as between types of Adult Education provision within the sector itself. Also, international results of studies often cannot be compared, since the instruments and national meanings of Adult Education differ considerably by country.

- Methodological challenges Finally, methodologically the analysis of learning benefits is challenging as it is seemingly hard to quantify the impact of Adult Education. Oftentimes the benefits evaluation is based on subjective valuations and on learners’ responses to surveys and interviews. Most of the studies focusing on Adult Education are either small-scale and contain little context information. Although in many countries large-scale data sets containing information on Adult Education are in development, in most countries representative longitudinal studies with the main focus on educational issues do not exist.

Summary: Which Evidence Can be Presented for the Wider Benefits of Adult Education Today?

In order to summarise: this paper argues that Adult Education affects people’s lives in ways that go far beyond what can be measured by labour market earnings and economic growth. Adult learning has positive outcomes and influences attitudes and behaviours that directly affect people’s well-being. Research indicates that Adult Education has a positive correlation with health (behaviour), intergenerational effects as well as the reduction of poverty and crime. It is shown that tolerance; open mindedness as well as civic engagement can be sustained and transformed by adult learning.

The data confirms that adult learners experience important “soft” benefits, such as increased self-confidence, self esteem and improved job-satisfaction. Specifically the feeling of achievement has positive effects on individuals’ self-image, enhancing the psychological well-being and thereby strengthening their identity. Benefits such as higher earnings and employability as a result of participating in adult learning interventions influence well-being indirectly.

Important as they are, the wider benefits of adult learning are neither currently well understood nor systematically measured. Although some change is apparent, the wider benefits of adult learning is still a poorly understood and emerging area, with a weak basis of theory and evidence. There exist only selective, individual studies that focus on adult learning and its learning. This means that there are substantial gaps in our knowledge base. Nevertheless, during recent years, there is a growing interest in the wider benefits and we can be generally confident in arguing that adult learning has demonstrable wider benefits, which is significant for both policy-makers and practitioners.

The Way Forward: Suggestion About the Next Steps

Resulting from the investigation for this paper, some recommendations for possible future courses of action can be made:

Holistic view There is still a call for a holistic attitude, beyond qualifications, certifications and economic benefits.

Further research and data collection One of the main challenges to research and evaluation in the Adult Education sector is the huge complexity and diversity of educational provision. Therefore it will be essential to provide better research, data collection and analysis. More coherent studies for understanding the effects and causes of (adult) learning need to be developed.

Development of Indicators Indicators should be developed which provide useful information for (inter)national policy makers. Because wider benefits are difficult to measure quantitatively and more complex than one single dataset, indicators are an important tool in order to enable to assess benchmarks and to monitor the education system.

Comparative studies Comparisons between countries and regions are needed in order to reveal differences among cultures and levels of development. These findings would help researchers and policy makers to consider new strategies and guidelines, planning and implementation.

More Investment It was clear from the consultations undertaken for this study that future research will depend on convincing government and research funding bodies. There is a need to invest in the quality of adult learning provision. Generally, it is not primarily a question of providing more specific adult learning but of recognizing and investing in the wider impact of general adult learning. There needs to be a better balance in the use of public resources.

Although some first evidence and answers concerning the wider benefits of Adult Education were given, there are further questions to be answered such as: Are the benefits distributed more or less equally across different types of learner? Or do some people experience stronger gains than others? Can we identify particular approaches that are more likely to produce wider benefits than others?

References

Beicht, U.;Krekel, E.; Berger, K.; Herget, H. And Walden, G. (2003) “Kosten und Nutzen beruflicher Weiterbildung für Individuen” Bonn: BIBB.

Bertelsmann Stiftung (2010) “The European Lifelong Learning Indicators (ELLI)”, www.elli.org

Bynner, J. and Hammond, C. (2004) “The benefits of adult learning: Quantitative insights”, London: Centre for Research on the Wider Benefits of Learning.

Canadian Council on Learning (2010) “CLI Composite Learning Index” www.cli-ica.ca

Desjardins, R. and Schuller, T. (2006) “Understanding the Social Outcomes of Learning” in Measuring the Effects of Education on Health and Civic Engagement: Proceedings of the Copenhagen Symposium, Paris: OECD.

European Association for the Education of Adults (2010) “The role of Adult Education in Reducing Poverty – EAEA Policy Paper” Brussels: EAEA.

Feinstein, L., Hammond, C., Woods, L., Preston, J. and Bynner, J. (2003) “The Contribution of Adult Learning to Health and Social Capital”, London: Centre for Research on the Wider Benefits of Learning.

Feinstein, L.; Galindo-Rueda, F. and Vignoles, A. (2004) “The Labour Market Impact of Adult Education and Training: A Cohort Analysis” London: School of Economics and Political Science.

Feinstein, L.; Budge, D., Vorhaus, J. and Duckworth, K. (2008) “The social and personal benefits of learning: A summary of key research findings” London: Centre for Research on the Wider benefits of Learning.

Field, J. (2009) “Well-being and Happiness” IFLL Thematic Paper 4, London: NIACE.

Ferrer, A. and Riddel, W.C. (2010) “Economic Outcomes of Adult Education and Training” Vancouver/Calgary: Elsevier Ltd.

German Socio-Economic Panel (2008) “Analytical Potentials of the German Socio-Economic Panel for Empirical Educational Research” Berlin: Deutsches Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung.

Manninen, J. (2010) “Wider Benefits of Learning within Liberal Adult Education System in Finland” University of Eastern Finland.

National Education Panel Study (2010) WZB, Social Science Research Centre, Berlin, http://www.wzb.eu/bal/neps/etappe8/etappe8.en.htm, accessed 11.02.2011

OECD (2007) “CERI – Understanding the Social Outcomes of Learning”, Paris: OECD.

ÖIEB (2008) “Was bringt mir Bildung?” Wien: ÖIEB.

Preston, J. and Feinstein L. (2004) “Adult Education and Attitude Change – Report No.11”, London: Centre for Research on the Wider Benefits of Learning.

Sabates, R. (2007) “The Effects of Adult Learning on Social and Economic Outcomes”, London: Commission of Inquiry.

Sabates, R. (2008) “The Impact of Lifelong Learning on Poverty Reduction” IFLL Public Value Paper 1, London: NIACE.

Schleiter, A. (2008) “Glück, Freude, Wohlbefinden – welche Rolle spielt das Lernen? Ergebnisse einer repräsentativen Umfrage unter Erwachsenen in Deutschland” Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung.

Schmid, K. (2008) “On the Benefits of Further Training – Participants Self-Assessment of the Causality and the Heterogeneity of Returns” Vienna: Institute on Research and Qualification of the Austrian Economy (ibw).

Schuller, T. (2000) “Crime and lifelong learning” IFLL Thematic Paper 5, Leicester: NIACE.

Schuller, T. and Watson, D (2009) “Learning through Life: Inquiry into the Future of Lifelong Learning”, London: NIACE.

Timmermann, D. (2010) “Public Responsibility for Continuing Education Shaping the Adult Education System through State Financing” http://www.psih.uaic.ro/cercetare/publicatii/ anale_st/2010/09dieter %20timmermann.pdf, retrieved 27.2.2011.

UNESCO (1997) “Final Report of the Fifth International Conference on Adult Education” UNESCO: Hamburg.

Wolfe, B. and Haveman, R. (2002) “Accounting for the Social and Non-Market Benefits of Education” http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/5/19/1825109.pdf, accessed 15.02.2011.