Alicia Cisneros / Nélida Céspedes

On top of social exclusion through poverty and marginalisation, indiginous people in many countries have to deal with the additional obstacle that their mother tongue is not the language of the dominant culture. Only true bilingual education in full recognition of indigenous rights and values can overcome the alienation that they confront as they enter school. Tarea is a Peruvian NGO with many years of experience in striving for social justice, human development and interculturality through education. Alicia Cisneros, a teacher from the region of Ayacucho specialised in bilingual education., and Nélida Céspedes, who serves as President of the Latin American Council for Adult Education (Consejo de Educación de Adultos de América Latina – CEAAL) in addition to coordinationg Tarea’s work in Ayacucho, describe how they assist the Peruvian educational authorities with the implementation of an intercultural bilingual education programme tailored to the regional requirements.

Learning in Rural Schools

An experience made in Ayacucho

Why Develop an Intercultural Bilingual Education in Ayacucho?

The Ayacucho context

The Ayacucho Region is one of the poorest regions of Peru. According to the HDI (Human Development Index) it ranks 21st out of 24 regions. The poverty rate is

68.3% and extreme poverty is at 35.8 %. Ayacucho has one of the highest rates of a population speaking a native language, specifically the Quechua (63.4 %), a figure that is above the national average (15.7 %). Despite having a high rate of primary school attendance (98.5 %), school completion rates are very low (64.5 %), which, among other reasons, may be because most of the children do not benefit from the Intercultural Bilingual Education (IBE) programs, that is to say, an education that emphasises cultural and linguistic heritage. It has also suffered historical neglect by the state, with manifestations of political violence and social exclusion, which has mainly affected the Quechua-speaking population. Education was not in accord with the real educational, cultural, economic and political necessities of the Ayacuchan people.

In the midst of this context and the complex process of decentralisation there have been steps taken to address the problem. One result is the Regional Education Project (REP). This project, which is part of official policy towards the region, was developed in a participatory fashion and seeks to strengthen a free public education which resonates with reality, with potentialities and with regional resources. It aims to overcome inequalities through the promotion of inclusion, critical reflection, dialogue and intercultural and bilingual relations. At present and within this framework there are several initiatives being undertaken with the aim of implementing the policies of the Regional Education Project in practice with a clear focus on Intercultural Bilingual Education (IBE); this is how the public investment project called “Development of teaching skills and their administration in Ayacucho” arose, whose goal is developing a regional curriculum for Ayacucho. Consequently, a Medium Term Plan was formulated within the framework of the REP with the following areas: regular basic education, alternative basic education, administration and early childhood. Moreover, the National Education Council (NEC)1 is developing activities in complement with the strategic objectives as far as management, planning and professionalism of teachers is concerned.

Included among the transformations to be achieved are: intercultural and bilingual dialogue; rural development; autonomous, participative and ethical management; democracy and quality education; training and re-evaluation of teaching and regional development. These changes have to be expanded according to the recommendations of the Commission of Truth and Reconciliation2, and be made concrete in the Medium Term Plan which organises and plans agreed policies and adjusts its budget so that education policy can be implemented by the regional government. This is the way it gets through the rhetoric to action.

In Ayacucho these advances have been made possible thanks to the work and influence of the Network for Quality Education, a network of NGOs with extensive experience in actions, activities and policies, and that from a critical position cooperates with the public sector to formulate and develop specific policies for the region, especially as far as regards Intercultural Bilingual Education. The Tarea NGO has extensive experience in this area.

Gathering the voices of the actors on behalf of IBE

In Paqcha, located in the district of Vinchos, one of the districts that make up the province of Huamanga, in 2005, information was collected from high school students who benefited from a Tarea project for student participation through so-called “student governments”, that is, school organisations that fight for their rights. When asked, “How does it feel to speak Quechua?”, 80 % of the 245 students surveyed said they feel good, compared to 8.1 % who said they felt ashamed. This data is important because many teachers say that students often reject their language and refuse to be educated in Quechua. The answers to the question “Where do you feel comfortable speaking Quechua?” showed that Quechua is only well-received in the family and community. Thus 45.5 % of respondents reported feeling comfortable speaking Quechua in the family, while 24.4 % felt good about speaking it in the community.

Quite the opposite occurs with the use of Quechua in school. Only 3.7 % of students reported feeling comfortable speaking Quechua with their teacher. This result is alarming, because school is a place where the mother tongue should be favoured as cultural identity and an expression of value in order to strengthen the self-esteem of students.

This data corroborated the opinion of the students in so far that education was not based on their culture and language. Moreover, the Quechua-speaking students were educated in Castilian and they are still, leading to problems of understanding with consequent experiences of failure and frustration. So indicates the national apprenticeship survey conducted in 2004, according to which 97.7 % of students do not achieve the expected learning outcomes in reading comprehension, while

98.7% don’t achieve the expected learning outcomes in mathematics. This problem is basically due to the fact that bilingual intercultural education has not been developed and implemented. This is an ethical problem because it violates the rights of indigenous peoples to education in their own language; an educational problem, because thousands of students do not achieve the expected learning outcomes and there is repetition and dropout; and a political problem because programs and educational policies do not address the needs of the populations that need to be educated with cultural relevance in a language other than

Castilian, while at the same time resources are not dedicated nor are teachers trained to provide quality education.

The institutional option

In its strategic plan for 2008-2011, Tarea (Association of Educational Publications) agreed to work for the right to bilingual and intercultural education for rural people in order to overcome the forms of exclusion in school and the design of monocultural school. We are faced with the need to deepen the intercultural perspective, understanding the school and the local area as environments for building equitable relations between the Andean culture and mainstream culture, with the aim of replacing the model of a school which excludes by a school which educates the construction of an identity as an act of the subject itself.

Teacher Education Program in IBE

What teacher training approach guides the program?

We start from a critical and reflective understanding of teaching. We say critical because it inserts itself in the context of a historical dynamic and refers to theoretical and practical elements in the profession. In this regard, we rely both on contributions of popular education in Latin America, which presents education as an act of transformation, as reflections of critical pedagogy, which in turn presents the teaching profession as a responsible answer to the right to education, committed to social equity.

This is a vision that is developing, building: knowledge about teaching is not prescriptive knowledge, that is to say, knowledge that can be prescribed to others so that they can implement it. We do not share in a technical rationality based on a codified and instrumental understanding of knowledge in the sense of positive science. We believe it is a knowledge that has to be shared and that it is in that space of dialogue between the different visions where our understanding of teaching will grow and be transformed. We believe that no one can try to impose on others the lessons from their own experience. They can only be shared and, if necessary, defended, but always with an open mind, because only in this way can they be converted into a proposal for professional, personal and civic growth for teachers.

This means that along with teachers, one should: analyse the historical framework in which various forms of teacher performance are embedded; develop an awareness of the ethical and political nature of educational practice in so far that a personal and collective position can be assumed in regard to a historical truth; develop an awareness of the social consequences that actions have on the lives of the people being worked with in a direct way; and achieving an understanding of the problematic nature of the educational experience which distances itself from the vision of efficiency of the subject teacher and that reduces the educational experience to a technical reality without recognising the cultural, epistemological and ethical complexity of teaching.

Therefore, the teacher is recognised here as a subject of knowledge, politics, culture – inserted sequentially in knowledge, politics and culture. It comes from them, is elaborated in their experience, which is living and thinking, and in this dynamic, teacher identities are configured.

The central component of the practice of teaching is pedagogical optimism. It involves the idea that every individual is educable, and this affirmation promotes a successful attitude regarding the intrinsic educability of all people, even in difficult conditions. Pedagogical optimism is not naive – rather, it requires that educators understand the reality of the contexts in which their students live and how these can prejudice or facilitate their learning.

Contributing to the formation of the professional in education, taking into account the whole situation is, however, a practice on which there has not been sufficient thought. In this sense, we believe that a critical and reflective perspective of teaching is relevant to the goal of contributing realistically to teacher education.

Curriculum focus

This concept is understood as related to a critical perspective in the context of a social logic

- committed to developing the whole person (a teacher who knows, masters the methods, knows the subjects with which she/he interacts as well as local, national and international demands, adopting a position of harmonious coexistence with nature and others);

- which relates knowledge to knowing how to do, allowing a permanent relationship between theory and practice as a continuum, making the action and reflection form positive attitudes in constant development;

- focusing on the subject known – not the object of knowledge – assuming it as the subject of rights;

- committed to the profession of teaching from a critical, reflective and analytical perspective, which allows for constant individual and collective renewal;

- which considers the capabilities, based on knowledge, of the people and their context, are dynamic and therefore require Lifelong Learning;

- which allows the teacher to adapt to social development and to its integral need to develop and learn collectively in cultural diversity;

- which allows one to act responsibly and conscientiously, taking into account the consequences of their actions.

Intercultural approach

- A critical interculturalism which differentiates itself from functional interculturalism. When one opts for critical interculturalism of a de-colonial nature, it is argued that it is not enough to just respect and value cultural and linguistic diversity or create processes of dialogue between people from different cultural traditions as suggested by functional interculturalism, rather one must intervene in the education of citizens and make them capable of creating new economic models, lifestyles and responsible consumption; capable of reconciling private interest with the common good.

- We assume interculturalism to be a political, ethical, cultural and educational approach. Political, because the programs and educational policies must be part of national priorities, regional and local, with programs and adequate funding; ethical, because it does not permit exclusion to exist in our country; cultural, because it is based on culture and diversity, and respects and promotes them as something of value; and, finally, educational, because it is cultural relevant and pertains to all students and includes their knowledge throughout the process of teaching/learning.

- It is expressed with the approach of citizenship because it is part of the recognition of the rights of all persons in a given context, which in our case means assuming that this is a pluralistic country with differences which are cultural, linguistic, gender-based, integration-related, etc., which vindicates the exercise of rights for all people.

- We advocate an intercultural and bilingual education, within which language is an important component that has to do with the development and maintenance of culture. Interculturalism also implies dialogue with other cultures, always starting with the affirmation of its own, with an attitude of appreciation and a sense of belonging and self-esteem, working to tackle the feeling of defeat that society has imposed. The emphasis is not to save or rescue, but to give an impulse. It is not an attitude of revision of the past but a promotion of the potentials of a cultural group in the present and in the future.

- In cultural dialogue we seek the recognition of knowledge, practices and beliefs of all cultures, but not as strategies which permit the dominant culture to assimilate any another. We understand the cultural dialogue as an encounter between equally valid rationalities and with an equal right to maintain their space, even in this intercultural “third space”.

- Interculturalism as a suitable approach to address the diversity of knowledge in the teaching/learning process.

Focus on citizenship

In a country so broken up, multicultural, and deeply immersed in a process of education such as ours is, it is necessary to build a citizenry in which individuals feel like inclusive members of the community, feel bound by a set of civic duties and responsibilities and feel they can participate and take responsibility for common projects such as, for instance, in the construction of a democratic society.

Consequently, we work with a broad interpretation that understands citizenship in cultural and political terms as an active exercise. From this perspective, citizenship is democratic when it promotes an active citizen in public life, who has developed a sense of belonging to a community whose members are recognised as equal in rights and dignity.

School as a privileged space for socialisation not only lends itself to teaching, but also so that the new generations can have an experience of participatory citizenship, exercising their rights as students, young people and citizens, in an environment where they share in all areas of organisation and school life, without exception, the ideals of education of the youth in civic values such as:

- learning to live with others in the community

- respecting those who are different,

- eliminating any type of violence in treatment,

- demonstrating ethical behaviour when intervening in the resolution of public affairs, giving precedence to the interest and welfare of the community above personal gain.

How has the Educational Experience in Intercultural Bilingual Education Developed?

In the following we explain the very complex process which led to the development of educational experience in IBE.

Visits to educational institutions in different districts of Huamanga

With the intention of selecting pilot educational institutions, different schools in the Ayacuchan districts of Tambillo, Chiara, Vinchos and Socos were visited. During these visits, we met with teachers, parents, students and authorities, with whom we held extensive discussions to find out their views on intercultural education. The feelings of most of them were for the rejection of it, especially among teachers, considering it traditional and not allowing students to connect with the modern world.

This process, which is to collect the assessments of the actors, is critical to any intervention since it allows for a basic starting point in regard to the knowledge and feelings of teachers, principals, parents and mothers. Beginning with this reality one can actually develop the set of strategies needed to motivate and engage everyone in the educational experience.

The selection of educational institutions

The selection of educational institutions was made according to openness, initiative and willingness of the principals and teachers, each of them being, however, from the districts of Vinchos, Chuschi and Socos, and the most interested in the development of bilingual and intercultural learning for their students.

In the field of education in general and in the context of teaching/learning as well as in the development of programs for intercultural and bilingual education in particular, the motivation of teachers is of particular importance. The teacher is the person who directly implements the program in their classroom and consequently influences its acceptance and the interest that arises. She/he decides on the educational activities that are undertaken and performed. It is the motivation of the teacher that determines whether the presentation is autonomous and continuous, leads to personal involvement, initiative and commitment to a change to higher quality education, which in this case is synonymous with a strong commitment to IBE.

The starting point of the experience

To start the intervention in Vichos, a baseline was defined. As we know, the baseline is the first measurement of all indicators covered by the project design, and enables recognition of the value of the indicators at the time of commencement of the planned actions, that is, establishes the ‘starting point’ of the intervention.

Taking into account several indicators that specify the development of a proposal for IBE in rural areas, the following indicators were developed and produced the results detailed below.

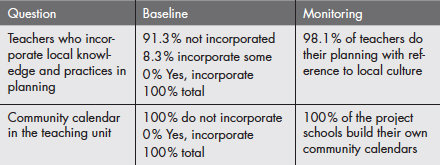

Indicator 1: Percentage of teachers who incorporate communal Andean culture as learning content.

It is important to know whether, in the teaching unit, the teacher incorporates the knowledge, local know-how and practices; if the community calendar is taken into account; if the activities and/or training sessions incorporate the use of materials from IBE.

Comparison Chart

Teachers incorporating communal Andean culture as learning content

When the baseline was defined in 2008, it was pretty disheartening to note that the educational practices of teachers were not based on the cultural and linguistic relevance of their students. Likewise, it was possible to corroborate the lack of education policies in this field, the neglect of the state in training teachers to service IBE, and lack of recognition of the importance of IBE as a component of progress by many teachers.

However, in 2011, thanks to the monitoring of teaching practices by an outside professional, we were able to see a significant achievement as far as the incorporation of local culture is concerned.

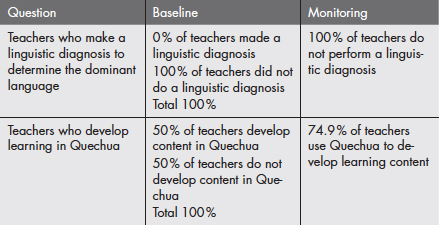

Teachers who incorporate Quechua in the learning process

As one can see, even on this point we were able to register progress in the performance of teachers. That is to say, these results and the previous ones clearly show that considerable progress has been made as far as a link between culture and language are concerned.

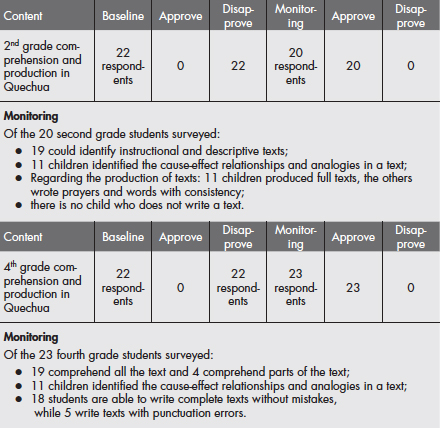

Results of the evaluation of children

Now we will look at the assessment of children in second and fourth grade in primary school who demonstrate skills in comprehension and production of text in Quechua.

(Monitoring report for 2011 from the Ruta del Sol project)

As we can see, the learning process requires the participation of both children and adults. For the adults, work was also done with the parents who live in the communities. This process has focused on identifying the members of the community who are wise and knowledgeable as well as people who master certain techniques and skills in accord with specialties, thus breaking down the preconception that an adult does not have knowledge, especially if the adult is a farmer.

On the contrary. Since ancient times, cultures have a cosmic way of seeing and understanding the world; that is, their experiences and philosophy are based on the understanding of the laws governing nature. Within these cultures, natural divisions in the social scale arose in which the initiates or those familiar with the mysteries, the yachaq, had and still have a key role in their communities, both religious, political and social.

Who is a yachaq? It is the sage who has received symbolic initiation as a teacher; which enables the building up of knowledge – of astrology, medicine, arts and sciences, – to put this knowledge at the service of the people. But it is more than that: it is the repository of culture and knowledge acquired throughout the history of a people.

Therefore, the educational proposition seeks to identify and register the knowledge-carriers and other villagers according to their specialties or the function they have in the community. Consequently, if we seek to identify a villager with a mastery of agriculture, the point of reference is to see who has the widest range of products planted; the corn farmer with this knowledge will be the one who knows how to plant and grow many varieties of corn. These are the people we want to share their knowledge so that their knowledge and skills are not lost.

As one can appreciate, the proposal for the development of IBE is directed at all those involved in the educational process, uses the knowledge-potential of everyone, and does this assuming an educational perspective which is comprehensive, holistic and inter-generational.

Moreover, the educational approaches of IBE, as well as their strategies and methodologies developed in the context of a teacher education program, produce the expected results. This is basically due to the fact that the adult subject is also taken into account.

Consequently, it is perfectly possible to make progress with this IBE proposal, affirming it with a set of policy documents to ensure that education constitutes a space for the defence and advocacy of interculturalism, as stated in the General Education Law No. 28044 (2003),3 which defines education as a human right for all people. It promotes equity at the very start of the educational process, which guarantees everyone equal access, permanence and equal treatment in a quality education system; it promotes inclusion, which includes people with disabilities, socially excluded groups, the marginalised and vulnerable, especially in the rural areas, irrespective of ethnicity, religion, sex or other cause for discrimination, thus contributing to the elimination of poverty, exclusion and inequality. [...], and interculturalism, which accepts the cultural diversity, ethnic and linguistic diversity of the country as richness, and recognises, in the respect for differences, as well as the mutual understanding and learning attitude of the other, a support for harmonic coexistence and exchange between the different cultures in the world.

Notes

1 The National Education Council NEC is a plural body, autonomous, consultative and specialised. It aims to promote cooperation and dialogue between civil society and the State in the formulation, evaluation and monitoring of the National Education Project, policy and educational plans of medium and long term and intersectoral policies that contribute to the development of Peruvian education. Thus, it promotes agreements and compromises in favour of educational development for the country and considers all matters pertaining to education as its business.

2 The Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) was a Peruvian commission primarily responsible for prepar ing a report on internal armed violence experienced in Peru during the period 1980 to 2000.

3 General Education Law No. 28044 (2003), Page 21