Monika Bayr / Roland Schwartz

Adult educators used to dedicate themselves to the tasks at hand without documenting the starting points or defining clear measurable goals of their actions. Thus, their work was based on assumptions, and its positive impact a matter of belief rather than of demonstrable proof. In times of tighter purse-strings for public spending, however, good intentions and claimed benefits that are not supported by measurable facts are not good enough to convince the funding agencies. Monika Bayr, in charge of monitoring and follow-up at DVV International, and Roland Schwartz, director of DVV International, describe the need for incorporating monitoring tools as an integral part of project planning and implementation.

Impact Measurement in Adult Education

Chinese proverb:

“If you are planning for a year, sow rice; if you are planning for a decade, plant trees; if you are planning for a lifetime, educate people” – Confucius

DVV International promotes the development of Adult Education systems in partner countries. This includes, along with the support of programs at the micro-level (specific measures for educational multipliers and target groups), the qualification of Adult Education institutions (meso-level) as well as advising the government on the design of a national Adult Education policy (macro-level). This three-tier approach is based on the belief that educational processes can only be successfully sustained if they are anchored through national laws and policies and are sustainably implemented and qualified by performance-oriented education providers.

Micro-level activities are aimed directly at individuals – for example, literacy courses, and courses for vocational training and further training.

At the meso-level, DVV International works with Adult Education organisations and institutions in order to sustainably improve educational opportunities.

At the macro-level, policymakers are advised and events are organised for the general community and for advocacy representatives.

Example: Well-building project in which wells are built in order to improve the living standard of the population and reduce illness. In the past, proof that the required number of wells had been built and these were of the intended quality was a measurement of success. Today the question asked is whether this has actually contributed to a reduction of disease. Very often it was then realised that the wells are there but that the people need to learn not only to use the water of the wells efficiently, but also to keep the wells clean so the water is not contaminated and doesn’t cause disease.

Education is a human right and, as such, initially without constraint to the development of an effect. Also, according to the ideas of Humboldt and Kant, education serves primarily to attain maturity and selfdetermination through the use of one’s mind. The humanistic quest for holistic education has to be free of economic considerations.

However, in real life, people educate themselves less and less “without purpose”, but rather undertake their educational efforts in the pursuit of objectives and more often the specific objective of earning their livelihoods with the acquired knowledge (livelihood skills) or to better get through life’s manifold challenges like, for example, to better care for their own and the health of their family and deal with life crises, to be able to participate in political decision-making, or for the very first time to be able to acquire the ability to learn general, transferable, soft skills.

Cultural, humanistic and non-utilitarian education is also part of a holistic understanding of education, but rarely found in development cooperation (DC). The understanding of education in the context of DC has to satisfy the accounting claim of the taxpayers of the donor countries. The support of education without defined goals in partner countries would be difficult to explain against the background of what are also latently underfunded education systems in donor countries. Education in DC therefore has to fulfil a purpose and to strive for a goal and an effect.1

From: D+C Development and Cooperation Vol. 38, 2011, page 447

German DC is committed to the overarching goal of poverty reduction, and the Adult Education programs also have to align themselves with this. A contribution of Adult Education to poverty alleviation lies in the fight against poor education which, according to the UNESCO definition, is present if time spent in school or learning is less than 4 years. Adult Education here has the function of providing remedial primary education for school dropouts or disadvantaged people who have never had the opportunity to attend school. But the mere measurement of learning time is only an “output” proxy indicator that does not allow for information on the educational attainment of a goal or educational effects. At least as important as the extent (time) of learning is the quality (content) of learning. One year of good learning conditions can have a more positive effect than five years of bad teaching. For this reason, for example the PIAAC initiative or PISA report 2 by the OECD, through a learning status investigation of students in a particular grade, can determine “output” indicators on the basis of learning results in order to draw conclusions about the quality and efficiency of the school system.

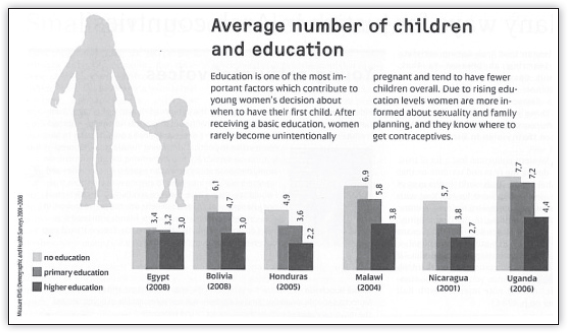

The interest to recognise educational efforts beyond the recording of “output” indicators in the OECD member countries is hardly noticeable. The question of the benefit (outcome), or even effects (impact) of learning achievement is pursued in the sciences,3 but does not come up sufficiently in the political debate. But nevertheless, it is rightly assumed that well-educated people are an advantage for positive development processes, for example where control over the number of births positively correlates with educational level (see figure).

Example: Micro-level

At this level, it is usually relatively easy to track whether activities show effects. Men and women learn, for example, to read and write in literacy classes in order to further their careers, in order to get information about prices in the market, or in general just to be independent. At the beginning of such a project it is possible to ask the people why they participate and want to learn particular things. After a certain time, the participants will be asked again what their new knowledge and their changing life circumstances really mean for them. The educational effects are made visible through this analysis.

Education is generally not viewed as a guarantor for personal, social and economic development, but regarded as its prerequisite. Whoever agrees with this plausible and empirically verifiable causal link between education and positive educational consequences is exempted from that ever-recurring, observable, manic-looking compulsion to define educational programs according to their societal “outcome” and “impact” indicators and to want to MESURE their results. In DC there should be no higher expectations for the measurement of educational effects

than are found in the education systems of the donor countries themselves. If it is possible to demonstrate learning achievements of students, educational programs have made their contribution to development. Whatever the effects resulting from the increase in the level of education for economic and social development of partner countries, it also, and significantly, depends on the – in parallel – changing environment of the political situation and the macroeconomic decisions which are made. Due to the complexity of development processes, all attempts to close the correlation gap between individual factors such as the level of education and the desired effect (poverty reduction) will fail in the long term.

Just because the effect of education on society as a whole cannot be detected due to the insurmountable correlation gap, the measurement of learning results (“output” and “outcome”) of individual education programs for the participants is that much more important. Here, especially in the field of Adult Education, there are still deficits to be found which contribute to the prejudice which is still often encountered that, in the education of adults in DC, what is being dealt with is unverifiable in effect and therefore is a subordinated development area.

Not in all, but in some areas of Adult Education, such as in literacy programs, the measurement of learning outcomes at a reasonable cost is possible and must in the future be carried out even more regularly than in the past. The well-intentioned tendency not to regularly measure learning benefits because the financial resources needed for the offer of additional literacy programs suffers, is not of service to the cause. On the one hand, the measurement of learning results is an important monitoring tool to ensure the quality of the learning offered and, if necessary to take corrective action afterwards. On the other hand, only with prior knowledge of the learning achieved is it possible to conduct further studies on the use of the knowledge gained. For literacy programs, in order to investigate the question of whether and to what extent the lives of people have changed after literacy succeeds and whether the acquisition of basic education has led to further education measures, “baseline and tracer studies” in particular would be a way to ask those questions. These benefit considerations, however, require a much greater financial commitment than the mere evaluation of the measurement of learning, and this is not provided in many development programs. In development projects whose duration is less than 3 years, the implementation of “tracer studies” is impossible because of the project design, since the time between start of the project and potential educational benefits in the education area covers a longer time span. In publicly funded long-term Adult Education programs, DVV International uses up to 5 % percent of its operative project volume for external evaluations,4 which however do not always contain enough information about the learning outcomes which have been achieved. This general deficit in external evaluations which has been determined in recent years, should be compensated for by an increased development of internal project monitoring, including the monitoring of learning success.

Example: Meso-level

In some organisations training for staff is offered, so that the courses they carry out are more participative, more realistic or more practical. Here, it is still relatively simple to follow if the new knowledge was also implemented and what the students think of it. Follow-up is more difficult, however, in the activities for organisational development: DVV International often supports organisations in the forging of networks. However, it is very difficult, if not impossible to prove that the network has a positive effect. In this field so many different factors play a role whose effects cannot be separated from the effects of the project: if the project, for example, takes place in a country where the government continues to block civil society organisations, this makes it more difficult and impairs the formation of networks significantly without drawing the conclusion that this is due to faulty project design. How should and can the contribution of the project be rated in relation to the conditions?

Adult Education in DC cannot be reduced to basic education. In more than 30 countries, DVV International also conducts educational programs for youth and adults in history awareness, occupational qualifications, political and health education as well as education for sustainable development. In these areas of work, the benefits of educational programs can also be shown, even if the learning outcomes there are not always quite as simply determined as in the literacy classes. For the educational training programs in Central Asia, for example, one project shows that after completion of a training program the benefits to the participants were that 52 percent could find a job or increase their income. This indicator is, however, not an effective proof of the training program, since the at least equally significant influence of macroeconomic conditions on these encouraging indicators is not quantifiable and therefore again a considerable correlation gap exists.

Conclusion: The measurement of the effect of Adult Education programs in development cooperation, because of the correlation gap between successful learning and the desired impact on development (poverty reduction) at the general societal level, is genuinely not possible. The learning outcomes of individual education programs in Adult Education need to be collected even more than in the past in the interest of their own research in the realm of project monitoring and evaluation in order to ensure the quality of educational processes and to even better illustrate the performance of Adult Education in development cooperation.

Example: Macro-level

DVV International supported the Ethiopian government which set itself the goal of reducing the illiteracy rate through the development of a National Education Plan. But how can one keep track of whether this master plan has achieved the desired positive effect? Here the correlation gap often becomes an insurmountable obstacle, because although a curriculum has perhaps been implemented, obstructive conditions – be it the lack of training of trainers, a drought or other adverse conditions – make positive effects impossible.

DVV International is working on impact measurement and also tries continuously to improve the existing monitoring and evaluation approaches through exchanges with other organisations and the Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development. Impact measurement must not mutate into an end in itself, but as a cost-effectiveadministered instrument it can help to further develop educational programs aimed at poverty alleviation.

Notes

1 Discussions regarding effect are taking place in DC using the following relevant terms, which were concretely formulated in an exemplary way in relation to literacy processes: Input: Provision of resources such as finance, infrastructure, personnel Output: Goals achieved through using the input, e.g. people who can read, write and calculate Outcome: People use their acquired knowledge and improve their lives in which they can, for example, read price tags and calculate product prices Impact: Long-term effect on society and the individual through the use of knowledge, for example, using the household income money saved through lower-cost shopping for the purchase of seed or better care for family members.2 PISA: Programme for International Student Assessment; PIAAC: Programme for International Assessment of Adult Competences.

3 Compare e.g. Eric Hanushek, Ludger Woessmann: The Economic Benefit of Educational Reform in the European Union, in Economic Policy, July 2011.

4 Compare: http://www.dvv-international.de/index.php?article_id=1061&clang=0