The world needs a clear target on Lifelong Learning for All for another world to be possible

Alan Tuckett ICAE,

United Kingdom

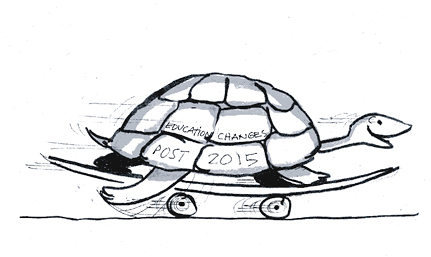

Abstract – This edition of Adult Education and Development marks a new beginning, and the International Council for Adult Education (ICAE) is delighted to be a partner with DVV International in presenting this set of essays and reflections on the issues under debate and discussion as new goals, targets and indicators are worked on for the period 2015– 2030. In this piece I offer a short review of ICAE’s work to date in seeking to influence the post 2015 global development targets, and review issues that need attention over the next year, as the UN system shapes its final proposals for overall goals, and a parallel process is developed for Education for All (EFA) beyond 2015.

The story to date

Ever since the eighth World Assembly of ICAE in Malmö in 2011 we have followed three key threads of the process which will lead to the adoption of new global development targets for the period 2015-2030. The first strand focused on the world Earth Summit conference in Rio in 2012. At this conference UN member states made the commitment to create Sustainable Development Goals, and commissioned 30 countries to lead an Open Working Group to report in 2014. Adult educators had only modest success at the summit in Rio in securing two discrete mentions of the Lifelong Learning agenda in the formal agreement of the conference, but ICAE made an effective alliance with other education civil society organisations, and led the preparation of a civil society policy paper on education for the world we want.

The second strand of our work was the Education For All process – which monitors progress on the range of education goals adopted at Jomtien in 1990 and confirmed in Dakar in 2000. Three of the EFA goals have a direct bearing on our interests. Target 4 makes a commitment to gender equality – but has in practice been focused overwhelmingly on access to schooling for girls. Target 2 commits to expanding learning opportunities for young people and adults – and whilst the EFA Monitoring Report in 2013 reported on skills for youth, no attempt at all has been made to monitor wider adult learning provision. Target 3 promised a 50% reduction in the numbers of adults without literacy skills – but in 23 years there has been an improvement in the literacy rate overall of just 12%, and numbers (just short of 780 million) are broadly static given the expansion of the world’s population. No improvement has been achieved in the proportion of women without literacy – still 64% of the total number.

ICAE and its partners have been relatively successful in influencing the EFA agenda, through the Consultative Committee of NGOs, the EFA steering committee, and the Dakar Consultation on Education, held in March 2013, which adopted an overall goal of “Lifelong Education and Quality learning for All”. All well and good – but the summary of the Dakar event still managed to omit any mention of adults.

The third process has been the work in considering what should follow the Millennium Goals. This has had a bewildering range of threads, co-ordinated by the UN Secretary-General’s High Level Panel (HLP), and we have found it difficult at times to see how best to contribute. The Panel reported at the end of May 2013.

The report, A New Global Partnership, is in some ways more positive than I had feared, but it also contains major and disturbing omissions, and clarifies areas where we need to redouble our advocacy. It provides, though, one clear context for our immediate discussions, and in my view highlights some key challenges the adult learning movement needs to address.

The report bases its recommendations on global goals on an analysis that five “big, transformative shifts” in priority are needed for a sustainable future in which poverty can be eradicated. These are:

- “Leave no one behind” – income, gender, disability and geography must not be allowed to determine if people live or die, or their opportunities. Targets are only to be achieved when they impact equally for marginalised and excluded groups.

- “Put sustainable development at the core” – the report argues that it should shape actions by governments and businesses alike. There is little, though, securing sustainable ways of living.

- “Transform economies for jobs and inclusive growth” – jobs are what help people to escape poverty but people need “education, training and skills” to be successful in the job market. There is, though, nothing on the need to strengthen the skills of people working in the informal economy – though these are the overwhelming majority in sub-Saharan Africa and in India.

- “Build peace and effective, open and accountable public institutions” – the report argues that freedom from conflict and violence are essential foundations for effective development, and that “a voice in the decisions that affect (people’s) lives are development outcomes as well as enablers.”

- “Forge a new global partnership” – including a key role for civil society.

A new global partnership then offers, for illustrative purposes twelve universal goals, each with between four and six sub-goals, to be accompanied by targets set nationally, and indicators that can be disaggregated to see the impact on marginalised groups. The targets are ambitious, wide-ranging, and as the report argues, interrelated:

- end poverty;

- empower women and girls and achieve gender equality;

- provide quality education and lifelong learning;

- ensure healthy lives;

- ensure food security and good nutrition;

- achieve universal access to water and sanitation;

- secure sustainable energy;

- create jobs, sustainable livelihoods and equitable growth;

- manage natural resource assets sustainably;

- ensure good governance and effective institutions;

- ensure stable and peaceful societies

- create a global enabling environment and catalyse long-term finance.

It is an impressive list, weakened by little clarity about how everything is to be paid for, but adult educators will recognise that few, if any of these goals can be achieved without adults learning – understanding, adapting to and shaping the changes that are needed. But it is perhaps no surprise that this is not a central conclusion of the report.

Nevertheless, there are things to welcome. First, the reassertion of human rights as the basis for development, and the determination that new targets should focus on ensuring that “no-one gets left behind”. The key proposal that no targets can be met unless they are achieved for each quintile (20%) of the income distribution, and that they are achieved for women, for disabled adults, for migrants, and for others previously excluded is reiterated through A new global partnership. The report recognises that for this to happen, there needs to be major investment in improving data, which can be disaggregated to provide accurate information on how effectively marginalised and excluded groups are reached. Improved household surveys, including questions about participation in learning would go a long way to assist adult educators in monitoring the success of programmes in meeting the needs of under-represented groups.

A second benefit is that the Millennium Development Goals and Sustainable Development Goals processes are brought together. It argues, like the Earth Summit that antipoverty and sustainable development goals must be developed hand in hand. It recognises, too, that the 12 goals identified are interrelated.

At first glance, the recommended goal for education looks positive, too. The third goal, to “provide quality education and Lifelong Learning” – at least includes Lifelong Learning on the agenda. Yet it differs from the Dakar education thematic conference in omitting any commitment to make provision “for all”. And when we look at the detailed targets we find that the one covering youth and adults is to “increase the number of young and adult women and men with the skills, including technical and vocational needed for work”.

This formulation of a Lifelong Learning goal – as yet only illustrative – fails to meet the challenge the High Level Panel set in their overview. They say: “Education can help us reach many goals, by raising awareness and thus leading to mass movements for recycling and renewable energy, or a demand for better governance and an end to corruption. The goals chosen should be ones that amplify each other’s impact and generate sustainable growth and poverty reduction together.”

Again, reporting on what young people told the panel, they note that what is wanted is “for education beyond primary schooling, not just formal learning but life skills and vocational training to prepare them for jobs ... they want to be able to make informed decisions about their health and bodies, to fully realise their sexual and reproductive health and rights. They want access to information and technology so that they can participate in their nation’s public life, especially charting its economic development. They want to be able to hold those in charge to account, to have the right to freedom of speech and association and to monitor where their government’s money is going.”

The proposed goal addresses hardly any of that agenda. Nor does it address the challenge identified in goal 2: “Empower girls and women and achieve gender equality”. There the Panel notes: “A woman who receives more years of schooling is more likely to make decisions about immunisation and nutrition that will improve her child’s chance in life; indeed more schooling for girls and women between 1970 and 2009 saved the lives of 4.2 million children.”

The report fails to mention adult literacy as an issue at all. Nor does it recognise that for all those currently excluded, or who missed out on quality education in the past, the right to a first or second chance education for adults – lifewide as well as vocational – is essential if no one is to be left behind.

What next?

For me, a key challenge from all the work so far is how to find a better voice for adult learning and education in the education community itself. We need to ensure that the energies of our colleagues in the wider educational community understand enough, and are convinced to include the case for adult learning and education (ALE), which is rights-based, and includes the right to literacy, vocational, democratic and civic education, education for well-being; for sustainable lives, that is alive to arts and culture, intergenerational learning, and respects diversity and difference. That was, of course, the essential vision of the UNESCO World Conferences on Adult Education CONFINTEA V and VI, but it is not yet a vision colleagues working in schools and universities automatically include in their advocacy. Adults, like children, need quality education from properly trained teachers. Children do better in school when their mothers learn. Early childhood education works better when families are engaged. We need to be better at stressing our common and interrelated goals, but also at explaining our own clear priorities.

Related to this, we have a major task in helping the wider development community to understand better the role education of adults has in securing other goals for overcoming poverty and securing a better quality of life. An early task for us is to enumerate for each of the 12 universal goals proposed in the High Level Panel report just how adult learning makes a difference, backed ideally by hard evidence – of the kind the Wider Benefits of Learning Research Centre in the University of London’s Institute of Education pioneered, and OECD (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development) has taken up. It will be important not to over-claim, but work in build ing that case would be a constructive use of the virtual seminar ICAE will run with DVV International following the publication of the journal. [For more information, click here].

Of course, the most important task of all, in my view, is to frame concrete proposals for a clear and easy to understand Lifelong Learning target, and to articulate the indicators that can be measured. Mine would include just a modest change to the High Level Panel report goal adding “for all” to the current formulation – to read “provide quality education and Lifelong Learning for all”. This will then inevitably involve recognition that Lifelong Learning covers formal, non-formal and informal learning.

My three indicators would start with adult literacy. It is a fundamental right – and we should secure universal literacy by 2030, with the number of adults without literacy halved in every country by 2020, and halved again five years later, with an immediate priority given to eradicating the gender gap in access to literacy.

Given that the new targets are to cover the industrialised as well as developing world, it also needs to recognise that literacy skills are context specific, and the millions with poor literacy skills should be identified, and their numbers reduced.

ICAE, like DVV International has a commitment to decent learning for decent work. Access to fit for purpose education should be accessible to people working in the formal and informal economy, and the participation gap between the numbers reached in the most affluent quintile of a country’s population, and those in the least affluent 20 percent should narrow with each five-year measurement of progress.

Thirdly, education for democratic engagement needs to be a priority. But since that is so hard to measure, and since the power of learning to leak from one domain to another is so strong, I would settle for an overall participation target – measured by household surveys, and with data disaggregated by all the groups highlighted in the HLP report. Then the indicator would again seek to secure a reduction in under-representation by marginalised groups.

I have concentrated here on the High Level Panel report, since it is the first attempt to bring the full range of issues together. But the parallel work of the Secretary General’s Open Working Group on sustainable development targets will, doubtless, shift the debate again in different directions, and we must be ready to argue the case for education for sustainability to include the themes discussed here. And then there will be a parallel process to identify Education for All targets for the world after 2015. There is, without doubt, a great deal to do. But the vision of a learning society where everyone can learn to know, to do, to be and to live together, laid out in the Delors report in 1996 has yet to be achieved, and it is well worth working for.

Reference

High-Level Panel of Eminent Persons on the Post-2015 Development Agenda (May 2013): A New Global Partnership: Eradicate poverty and transform economies through sustainable development. The Report of the High Level Panel of Eminent Persons on the Post-2015 Development Agenda. Available at http://bit.ly/1aF1nGJ

About the Author

Professor Dr Alan Tuckett was elected President of the International Council for Adult Education in 2011, just as he retired as CEO of NIACE, the national NGO in England and Wales representing the interests of adult learners and teachers. Alan was at NIACE from 1988, and among his achievements there was starting Adult Learners’ Week, which was adopted by UNESCO and spread to 55 countries. Earlier in his career he helped to start the adult literacy campaign in the UK. He is a visiting professor at the universities of Nottingham and Leicester, and will teach this year at Julius-Maximilians-University in Wuerzburg, Germany.

Contact

ICAE

18 de Julio 2095/301 – CP 11200

Montevideo

Uruguay

alan.tuckett@gmail.com

www.icae2.org