Should we give up on a literate world?1

Rosa María Torres del Castillo

Rosa María Torres del Castillo

Education specialist, Ecuador

Abstract – It seems the world is giving up the aspiration of a literate world. Before the year 2000, the aspiration was to eliminate or eradicate illiteracy. In 2000, the aspiration visibly shrank to “reducing it by half” by 2015. Even this much more modest goal has not and will not be achieved. Both Education for All (1990–2015) and Millennium Development Goals (2000–2015) have focused on children and on children’s access to primary education. Early childhood development and Youth and Adult Education have been systematically sidelined. In the Information Society, “digital illiterates” have become more important than plain “illiterates”. Can humanity claim progress when, at the same time that information

and communication technologies and the Internet expand in an accelerated manner, 775 million young people and adults cannot read and write?

Every year, for years and decades, we read the same thing: There are millions of illiterate people worldwide (two thirds are women) and little headway is made despite the recommendations, statements, events and even the recent United Nations Literacy Decade (2003‒2012), of which few knew about and which ended almost unnoticed.

“In almost 25 years of Education for All and already well into the 21st century, we are still a long way off from a literate world.”

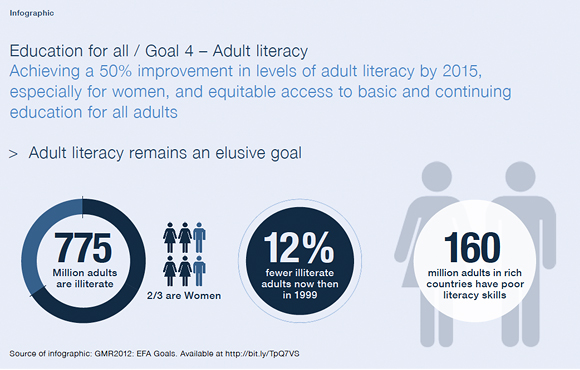

Infographics of the 2012 Education for All Global Monitoring Report graphically display the progress of the six goals of Education for All from 2000 (World Education Forum, Dakar) to the present. In all of the goals, progress has been lower than expected and less than what was pledged for 2015. Adult literacy is the furthest from being achieved: In 2010, there were 775 million illiterate adults, only 12% less than at the end of the century in 1999; the commitment to reducing illiteracy by 50% by 2015 is clearly unattainable at this stage. On the other hand, the report points out that 160 million adults in “developed countries” have “poor literacy skills” (see infographic on the next page). In 2010, the UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS) concluded that “literacy rates are increasing, but not fast enough”. In fact, progress has been insignificant and even more so if we go back a decade to the beginning of Education for All (EFA), to its launch at the World Conference on Education for All (Jomtien, Thailand) in 1990. The illiteracy figure disclosed by UNESCO as an EFA baseline was 895 million in 1989. The goal proposed at the time was also to reduce illiteracy by half – by the year 2000.

Therefore, in almost 25 years of Education for All and already well into the 21st century, we are still a long way off from a literate world. In Latin America and the Caribbean, the commitment to “eradicate illiteracy” goes back to 1980. The goal that captured the attention at a global level in all these years of Education for All and the Millennium Development Goals was primary education with a focus on access and enrolment. Early childhood education and the education of young people and adults, at both ends of the “school-age” spectrum, have always been pushed to the background, with the option of education of children versus education of adults being wrongly accepted, with the complicity of society.

History repeats itself when there is a race against time in trying to reach 2015 with what is possible and the issue of how to continue beyond 2015 is debated. The education of young people and adults, and specifically literacy, once again get relegated to the sidelines. Some demand that these goals be added, forgetting that they have always been there and what has been missing is the political will to fulfil them, both on the part of governments as well as the international agencies. Surely, this will once again end by adding a related goal and once again take the form of the usual salute to the flag.

“The number of illiterate people in the millions seems to have become perfectly tolerable and compatible with the progress of humanity.”

In a world that prides itself on having entered the Information Society with an eye towards the Knowledge Society, that boasts of technological advances and struggles to decrease the digital divide, that tries hard to gain points in the global rankings on poverty reduction, the “digital illiterates” are more important than those who are “just” illiterate. It seems to bother no one that those people who claim to be illiterate continue to number in the millions, swell the ranks of the poorest and dispossessed and will never read a book or benefit from the internet or broad band.

The number of illiterate people in the millions seems to have become perfectly tolerable and compatible with the progress of humanity. Who wants to take responsibility for them? Who wants to accept that the actual number of illiterate persons must be much greater since, as we well know, many people do not assess themselves as such in censuses and surveys? Who wants to pay attention to the failure of literacy education, to the worrying reality of the millions of people who cannot read or write even though they have formally learned to read and write?

The utopia of a literate world seems to be getting shelved away. Gone are the days of aspiring to end illiteracy (and poverty); the most that is aspired to today is the “reduction” of both in defined percentages and conveniently prorated. And there are even those who, from an economic calculation, ideology or simply ignorance, are ready to claim that the illiterate persons who live among us in the world today are surely impaired and incapable of literacy.

Renouncing the objective of universal literacy is not only denying a basic learning need and a fundamental human right that assists people of all ages and conditions, but the renunciation of one more piece of dignity and hope in an increasingly dehumanised world.

Note

1 This article has been published in Spanish on Rosa María Torres del Castillo’s Blog: http://otra-educacion.blogspot.com

References

Rosa María Torres del Castillo’s Blog: http://otra-educacion.blogspot.com

Tuckett, A. (29 April 2013): After Dakar: How does adult learning fit into post-2015 education aims? In: World Education Blog. Available at http://bit.ly/1eLIpjY

UIS-UNESCO (2012): Literacy and Education Data for School Year Ending in 2010. Available at http://bit.ly/1aiknwm

About the Author

Dr Rosa María Torres del Castillo: Ecuadorian, educationist, linguist, education journalist and social activist, researcher and international adviser specialised in basic education, reading and writing, innovation and Lifelong Learning. Worked with UNICEF and UNESCO in different capacities. In charge of preparing the Base Document for the UN Literacy Decade, and the Regional Report on Adult Education and Learning in Latin America and the Caribbean presented at CONFINTEA VI in Belém (2010). Minister of Education and Cultures in Ecuador (2003). Author of over 15 books and numerous articles on education and communication.

Contact

http://otra-educacion.blogspot.com

rm.torres@yahoo.com