Mission impossible? Creating a monitoring framework for Education for Global Citizenship

Amy Skinner

Amy Skinner

DEEEP/CONCORD

Belgium

Abstract - Education for Global Citizenship (EfGC) must be understood as a complex and multilayered process. It can be a force for transformation on the personal, local and system level. It would be a great help to be able to monitor the impact of EfGC taking this complexity into account. The article presents some research results on monitoring and explains the challenges in setting up a monitoring framework.

What is Education for Global Citizenship?

Education for Global Citizenship (EfGC) can be seen as an educational response to an increasingly globalised and interconnected planet. It is a transformative educational process which aims to create links between the local and the global in order to develop in learners a sense of belonging to a broader, world-wide community and common humanity. EfGC thus equips learners with the skills, understanding and values to become active citizens at both a local and global level.

There is no globally agreed upon definition of EfGC and there are significant debates about the concept and purpose, and indeed dismissal of the usefulness of the term. There are concerns that it is a predominantly Western invention, failing to recognise that for many around the world, access to the “global” or being a “global citizen” is not an everyday reality. Taking these concerns into account, I personally believe the most important element of EfGC is that it is rooted in the local context in order to make it relevant and to avoid abstract learning about topics or themes that certain groups might fi nd difficult to relate to.

Furthermore, it is a transformative form of education which uses participatory, active learning methods to encourage critical thinking and questioning, cultivate a recognition and understanding of different world views and a challenging of taken-for granted assumptions about the world. In this sense, it can facilitate transformation both at the personal level of the learner, as well as more widely in society and in education systems. Here Education for Global Citizenship draws particularly on the work of Paulo Freire and on popular education as well as Jack Mezirow on transformative learning.

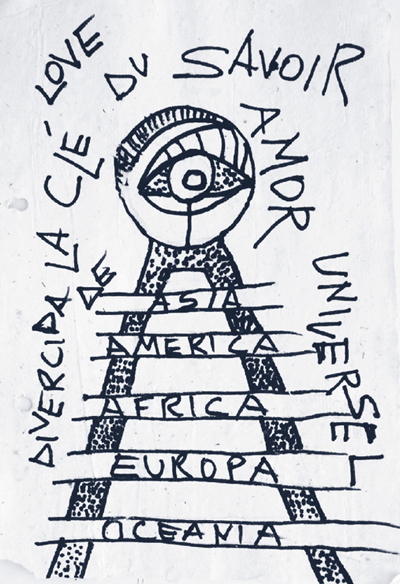

“The key of knowledge”

This transformative element was emphasised by participants at last year’s (2014) European conference Global Citizens for Education; Education for Global Citizenship co-organised by DEEEP (www.deeep.org). Participants came to a joint understanding of EfGC as “going beyond the acquisition of knowledge and cognitive skills, to transforming the way people think and act individually and collectively” (Fricke et al. 2014: 10).

Should we even try to monitor and evaluate EfGC?

The above understanding of EfGC calls for a monitoring framework which can capture the holistic and transformative nature of this form of education. Given the importance of process, it also calls for ways of monitoring which will pay attention to the pedagogical processes and learning environment, as well as the more traditional indicators related to inputs, outputs and outcomes. So how can this be done?

In a recent piece of research conducted in July-December 2014, we at DEEEP set about exploring the complex sphere of evaluation together with educational practitioners from around the world. They were all in one way or another working with EfGC. We wanted to find out about their key concerns and suggestions as to how best to understand and monitor the impact of the work they are doing. What follows is a summary of our findings. The full research report is available online. There you will find an in-depth discussion on the concept and purpose of EfGC and its monitoring.

Practitioners across geographical boundaries, as well as the formal and non-formal education sector, feel it is important to take into consideration the following concerns in developing such a monitoring framework:

Monitoring as a learning process

There is a need to change the mindset around monitoring and evaluation. It should be seen as a learning opportunity and a tool for reflection, learning and change. Monitoring and evaluation can be an inherent and important part of education itself, as opposed to a mechanism of control or to fulfil an external demand. This would involve including educators and learners not only in the development of monitoring frameworks themselves, but also in terms of analysing and learning from the data collected in order to reflect on and improve their practice.

Many respondents also felt that monitoring frameworks can actually help to strengthen the content and delivery of EfGC itself, as the process of monitoring inherently helps to “firm up” and clarify what EfGC is about, its purpose and aims. It is also an opportunity to monitor the content of EfGC more closely to ensure that it is relevant at local level. If done well, EfGC could include a mechanism for ensuring that countries are encouraged to develop their own content and programmes and avoid importing educational materials from elsewhere that are out of context.

That said however, many educators around the world are already overworked and monitoring and evaluation is often seen as another “burden”. They therefore tend to focus on what is being measured rather than on facilitating the learning through EfGC processes. Indeed, what is being “measured” tends to be determined by standard, predominantly quantitative and results-oriented monitoring frameworks. These are not suitable for EfGC, as they often fail to grasp the richness of the learning processes and tend to capture predominantly cognitive knowledge-based outcomes, when they should look at the skills, values and attitudes which EfGC holds so important. An alternative framework is thus required which can capture the holistic and transformative nature of EfGC and enable an understanding of monitoring as an empowering, learning process. This would need to go hand in hand with greater recognition, value and support given to EfGC from governments around the world in order to create an enabling environment for both the delivery and monitoring of EfGC.

In a globalised world, what are we educating for?

In many countries around the world practitioners felt that this is one of the key challenges that needs to be overcome, as there is often limited recognition of the need for and value of EfGC within educational systems. This often boils down to different understandings of the purpose of education itself in a globalised world. Whilst the educators in our research perceive their educational work being about empowering learners to become active and critically aware citizens of the world, many felt that education policy makers have a diff erent agenda and see education as about preparing learners to be competitive in the global market place. However, both education policy makers and practitioners tend to agree that current education systems need to adapt to a globalised world, and this was also considered by many educators as an opportunity for EfGC to assert itself and its agenda as an alternative to the market-based educational agenda.

This is particularly the case at the moment, as discussions for the post-2015 Sustainable Development Goal agenda are taking place. Discussions around the education goal include a proposed target on Education for Global Citizenship as well as the importance of monitoring quality in learning, as opposed to just access. EfGC is clearly an emerging educational perspective which is gaining increasing traction at various levels around the world. Many of the practitioners in our research felt that putting EfGC on the global agenda as part of the Sustainable Development Goals agenda would help support national endeavours to include EfGC within the education system, to challenge and/or counter-balance prevalent market-driven views of education.

Universal or localised monitoring frameworks?

However, many practitioners expressed concern about the imposition of universal monitoring frameworks and indicators which would inevitably accompany a target on Education for Global Citizenship as part of the education goal. They felt that identifying indicators that are meaningful across a large spectrum of socio-economic conditions, religious beliefs and cultures is a continued challenge, and that global targets and indicators can easily neglect the importance of diverse local realities, educational experiences and priorities, and favour Western educational ideals over indigenous education systems.

Thus the importance of recognising local realities within EfGC monitoring frameworks in order for it to be relevant and have a transformative impact was the first and foremost concern. As one respondent commented “...we see the most powerful change happen when people have a shared vision for their ideal sustainable future and the attributes/capabilities that a global citizen needs in order to realise this vision. When this is developed by communities themselves, it has much more meaning than some set of principles imposed from elsewhere” (Fricke et al. 2015: 33).

Practitioners suggested that this local-universal dilemma might be solved if universal principles were to exist (in terms of EfGC processes and basic characteristics of global citizenship) combined with national indicators and targets to show how and to what extent universal principles are to be met and how EfGC is interpreted in the country context. This could involve: a) stimulating “the creation, in each country, of indicators that include local specificities, considering the global targets” and b) encouraging “each country to establish comparisons between its own performance in different stages of the process, instead of comparing itself with other countries in different contexts” (ibid).

So what would a monitoring framework look like that refl ected these concerns?

This is not a question that can be easily answered, but we feel it is important to get the ball rolling and to start discussing and exploring alternative monitoring frameworks. Many Action experiences of the discussions about indicators and targets for EfGC apply a compartmentalisation of things to assess, based on the assumption that individual aspects of EfGC can be separately tested. The risk with such a “functionalist approach” is that the holistic intentions of EfGC – as a learning process that aims to develop and transform the disposition of learners (and of educators, and the education system) – are lost as a result. Monitoring EfGC needs to go beyond looking at the acquisition of knowledge, skills and values towards looking at the process and the interplay between:

- What is being learned: knowledge, understanding, competences (content and skills);

- How it is being taught and learned (process);

- What the learner does with her/his understanding(s) of content and with participation in the process (action, which could be in personal learning or other behaviour, in the school, in the local community, or wider society);

- How the educator and learner (and other interested parties) reflect on that relationship and change future process, content, action as a result.

In the final part of this article, I would therefore like to propose an idea which came out of our research, for a prism-based monitoring framework. This framework would aim to capture both the holistic, transformative and reflective nature of EfGC (see Figure 1).

An integrated EfGC monitoring framework, which includes the relationships between these different key components of EfGC could be used to identify the extent to which, for instance, the education off ered is:

- Relevant to the learner and the local context: as shown in the relationship between content & skills on the one hand, and action on the other hand;

- Facilitated: as shown in the process of teaching and learning of content & skills;82 Adult Education and Development

- Building experiences: through the educative process and through action.

The framework could be used for assessment at various levels including:

- At the level of the learner(s): assessing their own learning, and (in peer groups) those of their peers;

- At the level of the educator: assessing their teaching process and the chosen content and actions;

- At the level of the education institution: assessing institutional policies and practices;

- At the level of curriculum review and design: assessing the appropriateness of recommended themes, as well as the appropriateness of assessment techniques.

Some example questions to include could be:

- To what extent have facilitation and multiple-way exchanges between learner and learner, and learner and educator, made the acquisition of content and skills possible?

- To what extent has the process of teaching and learning enabled learners to gain new experiences, insights and skills?

- To what extent has the action been relevant to learning and vice versa?

- To what extent have the acquired content and skills been relevant to the action?

- To what extent did the facilitation and experiences stimulate learners’ active engagement in the issues addressed?

These are just initial ideas which we hope provide an initial basis for further exploration around appropriate monitoring frameworks for EfGC. This should be discussed amongst education policy makers, educators, education institutions, education and educator support organisations, NGOs and others (including parents and students) with an interest in education. The example given above is just one suggestion amongst many stemming from our research, so we warmly invite you to have a look at the report and use it as an initial springboard for developing monitoring frameworks relevant for your local and national contexts!

The full report can be accessed online at: http://bit.ly/deeepQuality

References

References Andreotti, V. (2006): Soft versus critical global citizenship education. In: Policy and Practice: A Development Education Review, Vol. 3. http:// bit.ly/1QiuxlG

Fricke, H.J., Gathercole, C. and Skinner, A. (2014): Monitoring Education for Global Citizenship: A Contribution to Debate. http://bit.ly/1zKcrW6

About the author

Amy Skinner is the DEEEP4 Research Offi cer at the CONCORD European NGO Confederation for Relief and Development. Amy Skinner holds a Masters in Development Education and a BA in International Relations and Development Studies from the University of Sussex, UK. She works both as a practitioner and a researcher in the field of global (citizenship) education.

Contact

DEEEP/CONCORD

10, Rue de l'industrie

1000 Brussels

Belgium

amy.skinner@concordeurope.org