Dieter Timmermann

Public Responsibility for Financing Adult Education

Public Responsibility for Lifelong Learning Will Grow in the Knowledge Society

The disappointing OECD PISA testing results of German pupils, and the recognition also of education as a saviour from the worldwide financial crisis, a crisis which has only worsened recession tendencies in a number of economic sectors in many countries, allow us to expect in particular nowadays that the state will continue to guarantee each citizen free access to a certain level of general education, and to initial vocational education and training.

The state bears the production costs of schooling and higher education, and supports learners’ families and adult learners as well, financing their living expenses if necessary. My hypothesis is that the transition into the knowledge society will broaden this public mandate. Simple occupations with low qualification requirements which can be performed without a minimum level of general education (especially in language and mathematics), and of social competencies, will lose relevance; the need for these will continue to decline steadily. Many adults either never acquired, or they lost, these basic qualifications due to their work and life conditions. Therefore, public responsibility for supporting learners is no longer restricted to young learners; it has to include adults as well. At the same time, the State has the task, by supporting vocational education and training, to support needy learners, to bridge liquidity gaps by loans, and to bear the risk respecting losses.

The Scientific Debate About Public Responsibility for Financing Education

Looking at the literature on the economics of education over many years, we observe the attempt to derive public responsibility for financing education from the distribution of the returns on and benefits of education. The general argument is as follows: education generates an enormous amount of societal benefit far exceeding the private returns to education. A problem of insufficient provision with education however arises: societal benefits exceed private returns, but the market demand for education does not reflect societal benefits; private demand for education is driven by the private returns. With respect to the societal needs for education indicated by the societal benefits there will be insufficient supply of education services. We find it asserted that the social benefits are highest from elementary and primary education, declining with each additional level of education and training.1 The conclusion is drawn that state intervention in education and the public financing of education should be restricted to general education up to a basic level, which should be defined by a societal discourse. Beyond that, only individuals themselves, their families, or private supporters, would be responsible for financing their education and training.2

However, it is conceded that individuals may have a liquidity problem in financing their education: except in very special cases the private banking markets for loans do not function properly with respect to financing education. Differing from the case of financing physical capital, human capital cannot be granted a loan. Therefore, the state would have to bridge the liquidity gap or liquidity trap by guaranteeing loans.3 Unfortunately, assumptions respecting views about the quantum of social benefits from education differ dramatically; empirical evidence is contradictory. Moreover, quite a number of social benefits named are not easy to quantify. Finally, the State has the freedom to decide whether it calls in the learner’s own contribution to finance education by tuition fees or loans, or later in life by progressive taxation.

However, it may be questioned whether public responsibility for financing education and training can be derived only from economic logic, rather than also from political value judgements and decisions.4 The state is then free to define the public mandate or mission, determine the instruments and shape the interventions. Likewise contributions of individual learners to financing their education can be called in by tuition fees or by progressive taxation.

What Does Public Responsibility Mean and How Can it be Brought into Practice?

To carry public responsibility means in principle that the state has to bear the consequences of decisions and actions itself. Of course, we know by looking at the financial crisis and the implications of the support activities of the different governments that at the end it comes to the tax-payers to bear the financial consequences.

The public responsibility for lifelong learning will grow in the knowledge society

-

the transition into the knowledge society willbroaden the public mandate for financing adult education

Simple occupations will loose relevance and theneed for them will steadily decline

The state has to support needy learners, to bridgeliquidity gaps by loans and to bear the risk ofdeficits

Whenever the state engages in favour of citizens, it takes initiating responsibility, rather than just responding to the demands of benefiting citizens. With respect to educational institutions which are run and financed by state authorities, the state is positioned within a triangle of public extraneous responsibility along with the extraneous responsibility of the educational institution (an institution for adult education like the people’s high schools in Germany), and the personal responsibility of the learner. In comparison to individual responsibility or to the private responsibility of a family, public responsibility is artificial. This means it is created by law or by contract, is chosen deliberately by the politicians, is determined politically, is often selective and directed towards a special issue, and can be dismissed, given up and cancelled. Public responsibility for adult education competes with responsibility for other public functions and goals inside and outside of education. It aims at advancing the common weal, and not directly the welfare of single citizens.

Public responsibility may be exercised using diverse channels or functions of different depth of intervention and effectiveness. One channel may be politics by means of setting rules by means of laws or decrees; a second may be politics by defining procedures (prescription of processes which have a moderating function); a third may be the politics of financing (full or partial financing of privately produced goods or services); a fourth may be the politics of material programmes, by which goods and services are produced by institutions run by the state; a final channel may be by means of politics which combine the production and financing of goods and services. These reflections lead to the distinction of four different functions of state behaviour requiring public responsibility: first, the function of designing a frame of political and economic order which defines the societal space for the diverse societal actors to act; secondly the function of offering moderation procedures to societal actors; thirdly the production function of offering publicly produced output; and finally the function of financing societal activities.

Taking up Public Responsibility towards Adult Education Requires Public Interest in Adult Education

The answer to the question: Which activities should be supported, produced or financed, to what extent and to what size, due to a public interest? Is the result of political bargaining and decision processes. “Public good is one that the public decides to treat as a public good”.5 According to the German Expert Commission on Financing Lifelong Learning,6 the distinction between private and public goods is a question of political will and bargaining; it always has to be renegotiated anew in the political sphere.

The Expert Commission on Financing Lifelong Learning argued that it might be possible to name areas of programmes and courses in adult education which allow for assuming a public interest, even a specific public interest to be offered and supported by the State. The rationale in favour of a public interest may be derived from the external benefits flowing from general, political and cultural education for adults. Maintaining social peace, increasing societal participation of individuals, fostering the acceptance of different norms and values within the range of values framed by the constitution, and practising citizenship engagement should be seen and valued as social benefits which would justify at least financial subsidies by the state in order to support educational programmes for adults in the area of general education, or even to make them possible at all.

A selective evaluation of adult education programmes led the Expert Commission to the assumption that a public interest may be directed towards the following

learning contents: first, political education; second, compensating basic education, such as German as a foreign language, or alphabetising courses; third, educational programmes dealing with the world of work, vocations and occupations, fourth, general education courses leading adults to basic schooling certificates and graduation; fifth, courses to support individuals in designing and mastering their daily lives including the ability to build up and cultivate social and intercultural relationships; sixth, programmes which aim at promoting key competencies such as mastering foreign languages and the use of the new media; and finally courses in family education. A specific public interest was observed to be devoted to citizenship and honorary engagement.

These propositions were led by the conviction that enduring and effective societal participation and lasting civic engagement will not be possible or sustainable without lifelong learning programmes in these areas. After all, one might argue that the necessity to ensure universal minimal living conditions in a federal state legitimates at least a partial state responsibility to subsidise general adult education.7 From a purely economic point of view, a public interest in public financing of education is assumed to exist, first in the case of external benefits, secondly if there are considerable restrictions on the availability and comprehension of information, and thirdly in the case of individual bottlenecks with respect to income and liquidity; in other words in the case of restricted ability to pay. These constellations include the danger of under-investment in education in general, and in adult education in particular, which however can be avoided by appropriate public co-financing.

Dieter Timmermann

Source: Barbara Frommann

Without adequate financing instruments, according to analyses by the OECD, there are high risks of under-investment in lifelong learning.8 The OECD offers a range of explanations. There is first the high probability that the total societal benefits from educational investments exceed the returns which the direct investor (the individual, the company, the state as the tax collector) may earn – the case of externalities. If each actor or investing unit only invests as much as would be rational and worthwhile in the light of their own returns (higher productivity of the company, larger income of the individual, higher tax revenue of the state, to name only the monetary returns to educational investments), the size of the total investment would fall below the optimal amount of investment which would be possible with joint financing.

A second reason for underinvestment in adult education comes from the fact that learning results are visible only in part, in the form of certificates or graduation titles. However, if the learning outcome is not transparent for potential future employers, the individual learner and future employee may not fully realise the economic value of their labour power and competencies.

Another reason may be added to those brought forward by the OECD. The costs of educational investment can usually be precisely measured. However, often the returns are not. The returns to education often only appear in the long run, and high degrees of uncertainty remain as to the question how far observed returns can be attributed to education or lifelong learning, or rather to other investment activities in an organisation. An economy and a society which looks primarily and short-sightedly at the costs, and ignores the long-term returns, even if only vaguely calculable, will under-invest in adult education.

One part of the benefit of educational investments – in particular social benefits like improving life quality, sustaining and strengthening social cohesion, and promoting democracy, which have neither direct utilisation nor a commercialisation dimension – is difficult or impossible to measure. The financing rationale cannot be derived from allocating returns to anyone. By developing financing strategies which are induced by the State and reflect the public interest, and which invite other actors to join a common “investment in lifelong learning strategy” by opening new chances for additional returns from education for several and different investors, the incentives for investing in lifelong or adult education will likely be enhanced for all actors. In the end, the level of investment in lifelong learning might be raised considerably. On this logic, effects and efficacy will follow, if an agreed-upon system of co-financing lifelong learning can be established. This conclusion meets the position of the OECD.

Participants from Africa

Source:

DVV International

Objectives of Financing Lifelong Learning in Germany

In its final report in 2004, the German Expert Commission on Financing Lifelong Learning presented a co-financing proposal aimed at helping to fulfil the following objectives:

- Promoting economic growth by

– Innovations induced through learning

– Strengthening lifelong learning in small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs)

– Promoting employability of the individuals - Integrating individuals into the labour market by promoting their

employability - Promoting societal participation and citizenship engagement

- Strengthening social cohesion

- Strengthening the openness and willingness to learn as well as the

responsibility of individuals - Strengthening their ability to choose, decide and behave rationally

in the markets - Aiming at balancing educational participation and financial burden

- Enduring the effects of the financing measures recommended if taken

- Efficient supply of manifold and effective learning offers and opportunities

- Creating market transparency with respect to suppliers, programmes and contents, certificates and their values, and quality of programmes and institutions

Motives for Intensifying Investment in and Financing of Lifelong Learning in Germany

The need to invest more in lifelong learning in Germany is based on the evidence which shows that in an international comparative perspective Germany has fallen behind most OECD and EU countries with respect to economic as well as innovative strength on the one hand, and with respect to willingness to engage and participate in learning opportunities beyond initial vocational education and training on the other.9

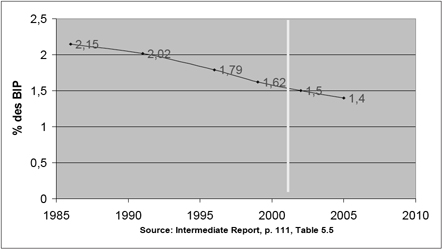

Thus, the proportion of the GNP which all actors (citizens, private enterprises, the state at local, state and federal level) have together invested in lifelong learning for adults declined from 2,15 % to 1,62 % between 1986 and 1999. Taking into account reported cuts to subsidies for adult education by local public authorities and some states during the present decade, coinciding with shrinking expenditures for continuing vocational training in companies, it can be assumed that the proportion of GNP has continued to decline since (figure 1).

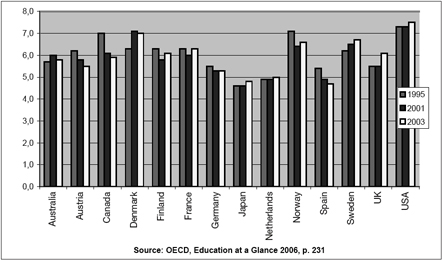

Figure 2 shows that German private households, companies and public authorities together have spent below the OECD average for education as a proportion of GNP between 1995 and 2003. Only Japan, Spain and the Netherlands spent less.

Fig. 1: Total Expenditures for Lifelong Learning in Germany, in % of GNP

Fig. 2: Educational Expenditures (private and public) in % of GNP

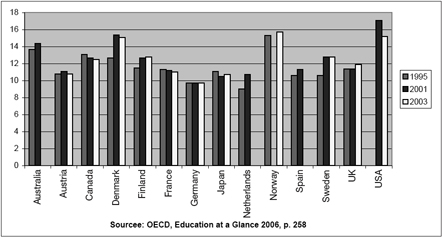

Even the public authorities seem to be less devoted to education (Figure 3). The share of the total public budget which goes to education is the lowest of all OECD and EU countries (among the latter before the last expansion) during the period observed.

Fig. 3: Public Expenditures for Education in % of Total Public Expenditures

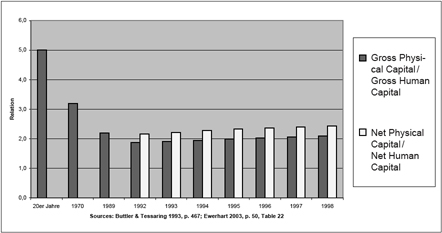

Moreover, we should be worried that German society, being at the threshold of the knowledge society era, seems to have invested more in physical capital than in human capital in the 1990s, reversing the trend since the mid-19th century (see Figure 4)

Fig. 4: The Relationship between Physical and Human Capital in Germany

Looking at individuals’ chances to participate in lifelong learning, a number of groups who can be defined by specific attributes suffer from chances significantly far below average. These groups are:

- Persons without, or with low, formal vocational education and training

- Persons working in occupations requiring little formal knowledge and being exposed to obsolescence

- Persons working in traditional (tayloristic) work organisations

- Persons without jobs or with precarious occupational status

- Workers and employees in small firms

- Women with children, in particular single mothers; the deficit in lifelong learning rises in parallel with the number of children

- Persons with low incomes

- Migrants of both sexes

It came as a surprise that, contradicting earlier findings, age and part-time work do explain below average participation. Instead, the number of children and the parental status of women as well as the occupational status of those over 55 years of age are the explanatory variables.

It seems that those who suffer from broken educational biographies and development paths, most of whom are drop-outs from schools – about 9 % of all pupils leave the German school system without having earned the lowest school examination certificate (data from 2006/07) – have the lowest chance of participating in lifelong learning as adults. The tendency is tottering back and forth; by far the hardest hit are young male migrants. A second subgroup of these young people are those who drop out from vocational education and training, most of them from the dual training system. Nowadays, about one quarter of those who begin with a training contract quit the training and the firm (in 1984 the ratio was only 14 %); two thirds stay in the training system, choosing another firm or another vocation. However, one third disappear. Finally, high proportions of immigrants with low education do not find access to lifelong learning; immigration is often connected with broken educational and occupational biographies. The conclusion in the light of the findings and analysis is that in Germany there is a very high and strong need for a second chance to learn.

Including the disappointing results from testing the knowledge and competencies of pupils by PISA and TIMS, we may sum up as follows:

- The German school system does not realise the learning and performance potential of its learners; other countries fare much better.

- On average, German enterprises do not adequately satisfy the learning and performance potential of their personnel. Companies in other EU and OECD countries do more.

- In the years soon to come, the German work force will shrink and age due to demographic processes. If things stay as they are now, the rate of economic growth will decline.

- As the workforce shrinks and ages, the average age of the workforce will increase, meaning that the ability and potential for innovations will increasingly depend on workers and employees who are growing older.

- The knowledge, which is accumulated in firms and organisations will also age and will, with the accelerating production of new knowledge, be hit by an accelerating process of obsolescence. The influx of new knowledge by recruiting new cohorts of graduates from higher education is in danger of slowing down, unless firms intensify and broaden their investment in the lifelong learning of their personnel.

- Having the demographic future as a background and taking notice of the newest results of research about learning of adults, a change of views is urgent, at least in Germany. It has not only to be acknowledged that adults and in particular the elderly are very well able to keep on learning and to stay productive, but society, its enterprises, schools, institutions of higher education, and institutions of continuing learning have to offer all these potential learners opportunities to learn lifelong, and to stay productive as well as innovative.

- Therefore, we must direct our efforts into new resources for stimulating lifelong learning. We urgently need

– To open up new mental resources for lifelong learning, in the form of willingness and motivation of all citizens to learn lifelong,

– To offer time to the potential learners so that they can learn,

– Physical resources and facilities to create the necessary learning places and environments,

– Financial means which are necessary to finance the purchase of physical as well as human resources in order to organise learning arrangements or to support learners in learning, or in bearing their living expenses while learning,

– To offer work places and work environments which do not only allow for learning at the work place or in the work organisation, but which provoke and stimulate learning.

Public Financing of Adult Education as Part of a Financing System for Lifelong Learning

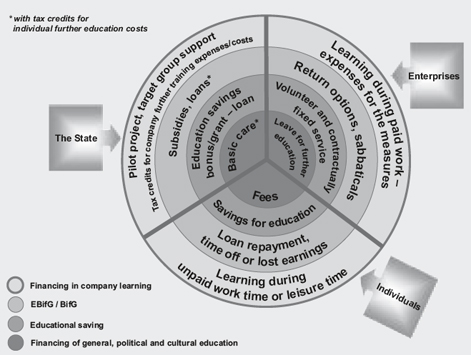

In its final report, the Expert Commission on Financing Lifelong Learning has proposed an architecture of co-financing lifelong learning led by the intention to design a system of lifelong learning and its financing which includes the societal responsibility for financing lifelong learning of the federal state as well as the 16 states, the enterprise sector, and citizens themselves.

The Potential Power of the Instruments Proposed Lies in their Combination

The proposal of the co-financing architecture allows and aims at combining resources from different financing sources. Thus one could imagine a worker without a vocational certificate taking leave of absence to make up for a certain school grade. He or she covers the need for learning time from an in-company learning time account and takes an add-on to subsistence from a personal educational saving account. Or an unemployed person would have the opportunity not to use unemployment compensation but to get support by the proposed law to foster adult learning in order to make up for a school grade which would allow entry to a vocational qualification programme afterwards. An even more efficient way would be to combine making up for the general education grade and the vocational training in a parallel manner. This would require close cooperation between the different institutions in charge.

Figure 5: Co-financing of Lifelong Learning – Instruments and Inputs of the Actors

Source: Expert Commission (2004), final report, manuscript version, p. 189

Providing money is not enough alone to raise the education participation rate. Applying the instruments for co-financing lifelong learning needs an education- friendly environment. Part of this is “soft factors”: a positive image and value of learning; encouraging lifelong learning by the public authorities, but also by entrepreneurs and managers as well as by the general public and the media. Societal appreciation of the work of personnel in learning institutions, whenever it is well earned, is also part of the recognition of lifelong learning.

References

Bock-Famulla, K. (2002): Volkswirtschaftlicher Ertrag von Kindertagesstätten, Gutachten im Auftrag der GEW, Bielefeld.

Buttler, F./ Tessaring, M. (1993): Humankapital als Standortfaktor. Argumente zur Bildungsdiskussion aus arbeitsmarktpolitischer Sicht, in: Mitteilungen aus der Arbeitsmarkt- und Berufsforschung (MittAB), 26. Jg., Heft 4, pp. 467–476.

Ewerhart, G. (2003): Ausreichende Bildungsinvestitionen in Deutschland? Bildungsinvestitionen und Bildungsvermögen in Deutschland 1992–1999. Beiträge zur Arbeitsmarkt- und Berufsforschung, Beiträge aus der Arbeitsmarkt- und Berufsforschung (BeitrAB) 266, Nürnberg.

Expertenkommission “Finanzierung Lebenslangen Lernens” (2002) (Hrsg.): Auf dem Weg zur Finanzierung Lebenslangen Lernens. Zwischenbericht, Bielefeld.

Expertenkommission “Finanzierung Lebenslangen Lernens” (2004) (Hrsg.): Finanzierung Lebenslangen Lernens: Der Weg in die Zukunft, Schlussbericht, Bielefeld.

Friedman, M. (1974): Die Rolle des Staates im Erziehungswesen, in: Hegelheimer, A. (Hrsg.) Texte zur Bildungsökonomie, Frankfurt-Berlin-Wien, pp. 180 ff.

Grabka M./ Kirner E. (2002): Einkommen von Haushalten mit Kindern. Finanzielle Förderung auf erste Lebensjahre konzentrieren, in: DIW-Wochenbericht 32.

Kucera, K. M./ Bauer, T. (2000): Volkswirtschaftlicher Nutzen von Kindertagesstätten. Welchen Nutzen lösen die privaten und städtischen Kindertagesstätten in der Stadt Zürich aus?, Bern.

Malkin, J. & Wildavsky, A. (1991): Why the traditional distinction between public and private goods should be abandoned. In: Journal of Theoretical Politics, Vol. 4, Nr. 3, pp. 255–278.

OECD (2003): The Policy Agenda for Growth. An Overview of The Sources of Economic Growth in OECD Countries, Paris.

OECD (2006): Education at a Glance 2006. Paris 2007.

Palacios, M. (2003): Options for financing lifelong learning, World Bank Policy Research Paper 2994, März 2003, Washington DC.

Timmermann, D. (1998): Öffentliche Verantwortung in der Weiterbildung, in: Elsner, W./ Engelhardt, W.-W./ Glastetter, W. (Hrsg.): Ökonomie in gesellschaftlicher Verantwortung, Sozialökonomik und Gesellschaftsreform heute, Berlin pp. 335–354.

Woodhall, M. (1995): Returns to Education, in: M. Carnoy (Hrsg). International Encyclopedia of Economics of Education, 2. Auflage, Oxford – New York, Tokyo, et. al. 1995, p. 25 (pp. 24–28).

Notes

1 see Grabka/ Kirner 2002 and Bock-Famulla 2002, Kucera/ Bauer 2000; see also Woodhall 1995, p. 25.

2 see Friedman 1974.

3 see Palacios 2003, p. 4

4 see Timmermann 1998.

5 Malkin, J. & Wildavsky, A. (1991): “Why the traditional distinction between public and private goods should be abandoned”. In: Journal of Theoretical Politics, Vol. 4, Nr. 3, pp. 255–278.

6 Expert Commission on “Financing Lifelong Learning” (2004), manuscript, p. 198.

7 With respect to the legitimation of the role of the state in adult education see; Timmermann 1998.

8 See OECD 2003.

9 See expert commission (2004), final report, chapter 2.2.