Women’s empowerment has been an issue of concern for decades. Though a survey on the women of the Mo communities of Ghana reveals a high level of participation in decision-making both at home and in the community and some level of economic independence, much needs to be done to further enhance their skills for higher education, income generation and participation in decision-making. This paper shows how functional literacy education could be used to facilitate empowerment among women in a developing community. Olivia Tiwaah Frimpong Kwapong has just completed her studies as a Special (PhD) student at GSAS, Harvard University and an ABD doctora student at the University of Ghana. She is a Lecturer in Principles of Adult Education and Programme Management at the Institute of Adult Education, University of Ghana, Legon.

The attempts to empower women have travelled through the decades. Considerable efforts have been made by governments and other agencies, and most especially the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) have been established to address women’s needs and their exclusion from the benefits of development. It is stated under the third goal of the MDGs on promoting gender equality and empowering women that women have an enormous impact on the well-being of their families and societies but their potential is not realized because of discriminatory social norms, incentives, and legal institutions (WBG http://ddp-ext.worldbank.org/ext/MDG/home Date Accessed09/09/05).) In the process of promoting and achieving

women’s empowerment, several policy approaches have been used. It is said that though the Women in Development (WID), Women and Development (WAD)/Gender and Development (GAD) strategies that shaped policy interventions and informed scholarly reflections in the 1960s and 1970s were limited by the fact that they remained within the established parameters of the state-led model of development and the discourses of its organic intellectuals, these approaches went some way in addressing some of the gender-based contradictions in the development process. (CODESRIA, 2005)

Over the years adult education has been used as a tool for improving the lot of people through capacity building. Based on the findings of a survey on women in the Mo communities of Ghana, this paper assesses how adult education could promote empowerment among women, most especially those in rural communities. The first part of the paper discusses the women’s empowerment concept. This is followed by a survey report. The final section of the paper shows how adult education could be used to facilitate empowerment among rural women.

Private researchers, donor literature, policy documents and several other literatures have shared views on women’s empowerment. Karl (1995) remarks that long before the word became popular women were speaking about gaining control over their lives, and participating in decisions that affected them in the home and the community, in government and international development policies and adds that the word empowerment captures this sense of gaining control, and of participating in decision-making. The word has entered the vocabulary of development agencies, and other international organisations.

In defining the term empowerment, Karl (1995:14) explains what power means to her as:

| Women who participate in literacy programmes have better knowledge of health and famliy planning, and are more likely to adopt preventive health measures |

| Source: UNESCO, EFA Global Monitoring Report 2006. Literacy for life. Summary, p. 17 |

Women’s empowerment could be briefly explained as the process of improving the human capital of women for effective participation in all aspects of development of a nation. This will make women become makers of development and history, not just receivers or objects of it. Women need not be just objects or beneficiaries of development but the development process of a nation needs the equal participation of women as well. Given that women form over 50% of the world population, their capacity building is crucial for holistic development. Women’s empowerment could also be said to comprise building their capacity or making the best of the lives of women for governance and socio-economic advancement. It is obvious that access to literacy or education, information or knowledge resources, natural or material resources, productive skills and capital facilitates the empowerment of women.

It could also be observed that culture, tradition, formed opinions and perceptions all combine to define a marginalized status for women in society. Efforts will therefore have to be made to transform the patriarchal society through conscientization and awareness creation. In this process traditions, structures, institutions and ideologies that have contributed to the discrimination and subordination of women will have to be challenged. Some of these traditions and structures include the extended family, the caste system, ethnicity, religion, the media, the law, policies, and top-down development approaches as against bottom-up or participatory approaches among others.

In providing a women’s empowerment framework Karl (1995) gives five levels which include welfare, access, conscientization, participation and control. These levels also reflect the various approaches that have been used to promote the empowerment of women over the years.

The first level, welfare, addresses the basic needs of women. This approach does not recognize or attempt to solve the underlying structural causes which necessitate provision of welfare services. At this point women are merely passive beneficiaries of welfare benefits. It is obvious that such an approach promotes dependence on the provider.

Access, the second level, involves equality of access to resources, such as education, opportunities, land and credit. This is essential for women to make meaningful progress. The path to empowerment is initiated when women recognize their lack of access to resources as a barrier to their growth and overall well-being and take action to address it.

Conscientization is a crucial point in the empowerment framework. For women to take appropriate action to close gender gaps or gender inequalities there must be recognition that their problems stem from inherent structural and institutional discrimination. They must also recognize the role they can often play in reinforcing the system that restricts their growth.

Participation is the point when women are taking decisions alongside men to ensure equity and fairness. To reach this level, however, mobilization is necessary. By organizing themselves and working collectively, women will be empowered to gain increased representation, which will lead to increased empowerment and ultimately greater control. This level reinforces the mainstreaming approach which proposes that the concerns of both men and women be recognized and integrated into all plans, policies, programmes, goals, objectives, activities, and monitoring and evaluation indicators. This implies that in all interventions, implications for women and men should be assessed in all areas at all levels. Another implication also is that though there might be the need for special programmes to bridge existing gaps, this should be for a period of time in a project’s life cycle in order to avoid creating another imbalance.

In the framework, control is presented as the ultimate level of equity and empowerment. At this stage women are able to make decisions over their lives and the lives of their children, and play an active role in society and the development process. Further, the contributions of women are fully recognized and rewarded as such.

This framework shows how since the early 70s the women’s empowerment processes have travelled from Welfare, Women in Development, Gender and Development, to Mainstreaming and Empowerment. A study on Gender Mapping (2000) also emphasises that key fundamental changes in the way all governments and agencies address women’s concerns have been from Women in Development (WID) to Gender and Development (GAD); and from targeting to mainstreaming. It is obvious that most of these approaches overlap but this shows the trend of progress. In all these stages of progress, there are bound to be draw-backs and inhibiting factors, which inform the strategy or approach that follows. Despite the constraints and challenges, one could say that much has been achieved towards the empowerment of women.

Karl’s (1995) study identifies the measures commonly used by development agencies to include empowerment to increase women’s economic status through employment, income generation and access to credit; and empowerment through integrated rural development programmes in which strengthening women’s economic status is only one component along with education, literacy, the provision of basic needs and services, and fertility control. In recent terms focus has been on integrated quality health care provision, inclusion in sustainable natural resource management, full participation in governance especially at the grass roots level etc.

A survey was conducted to find out the level of empowerment among the women of the Mo communities of the Brong-Ahafo Region of Ghana. The objectives of the study were to assess how the bio-data of the respondents affect their level of empowerment; observe the level of empowerment attained by the women in education; identify the skills that the women had developed to be able to carry out their economic activities; determine the level of the women’s participation in decision-making in the home; and measure the extent to which the women took part in decision-making in their communities.

The survey was conducted among a total of 200 women of the Mo communities of the Brong Ahafo Region of Ghana. The distribution was 66 from Weila, 61 from New Longoro, 39 from Bamboi and 34 from Ayorya.

The position of the women in the Mo communities is complicated and challenging. The females are more disadvantaged than the males. The Mo communities have features of a rural community as well as high population pressures, decreasing agricultural yields, land degradation and de-forestation as well as traditional problems with poverty and gender inequalities. The women do most of the farming; they are excellent traders and run several businesses. As a result of these, many other projects have used the women’s groups for village level activities (Ghana-Canada In-Concert, 2000).

A survey instrument of five sections and 34 items was used to elicit information from the respondents. The instrument included both closed and open-ended questions. Section one was on the personal characteristics of the respondents. It consisted of five items, which questioned respondents on their age, level of formal education, religious affiliation, marital status and major occupation. The second section was designed to elicit information on their level of educational empowerment. It was made up of seven items. The major issues that were raised included the influence of education on their socioeconomic life, their desire for further training and their initiatives to enhance female education. The third section was made up of twelve items to test the women’s level of economic empowerment. This section had the highest number of questions. The questions were based on the women’s access to farmland, their income-generating activities, the influence of their spouses on their income-generating activities and their means of saving money. Section four was designed to find out the women’s level of participation in decision-making in the home. Five items were embodied in this section.

The issues raised were the women’s ability to share ideas with their spouse, the type of decisions that they were able to take and their ability to decide on their own when handing over their properties to their heirs. The final section of the survey instrument was structured with the main aim of finding out the women’s level of participation in decision-making in their communities. In all there were five items. The major issues questioned the women’s affiliation to any women’s organization, the benefits they derived from the associations, their ability and opportunity to express their views in public gatherings and the extent to which their views were taken into account. The entire survey instrument included 31 closed questions and three open-ended items. While the closed questions yielded standardized responses, the open-ended items gave the women the chance to express their views in their own way. Field data was collected with the support of research assistants who were trained teachers from that locality and spoke the local language. The people were interviewed in their local dialects (Twi and Deg) to enhance accuracy of the results.

In order not to inconvenience the women, the interviews were done in their various houses. This approach was mainly associated with the problem of a few interruptions from household members and customers of the traders. However at the end of the day the researcher got the required information. The women also had the chance of sharing their experiences. The interviews lasted for a period of four weeks (28 days).

The subjects (94%) fell within the active years of 21–60. They were in their independent adulthood stage of development and for that matter formed the labour force of the community. Generally the respondents had a low level of formal education, with 33.9% of the women being illiterates and 44.8% having schooling up to the basic level (Middle, Primary, Junior Secondary Schools). Almost all the respondents had a religious affiliation. The majority were Christians followed by Moslems and Traditional Religious believers. As many as 77% of the women were married, only 13.7 were single. With 71% of the women being farmers, and 68.3% indicating trading as their non-farming income- generating activity, farming and trading emerged as the major occupations in the area. The most encouraging aspect of the women’s state of occupation was that the issue of unemployment was not prevalent among the women. Almost all the women reported being engaged in some form of income-generating activity be it farming or petty trading.

From the study it was observed that the women had a low level of formal education. About 32.8% of the women had no formal education, 44.89% were schooled up to the basic level and 1.16% had attended training college. Meanwhile the desire of 97% of the women to participate in training programmes to upgrade themselves and their careers implied that the women were determined to enhance themselves. At the same time as many as 94% reported being keen on promoting female education.

The results revealed that almost 99% of the women engaged in income-generating activities; 97% reported being able to manage their own income- generating activities; 83% were allowed by husbands to decide on how to use their own money; 88% of the women had access to land for agricultural purposes; 83% were allowed by their husbands to cultivate for commercial purposes; 63% were capable of controlling or managing their own income; and 94% of the women were strongly determined to partake in any training programme to upgrade themselves and improve upon their career. Based on these results, it could be emphasized that the women had a high level of economic independence. It was further observed that 64% of the women depended on their husbands because they did not have a regular source of income. This implies that the women need to be strengthened or assisted in order to reduce their level of dependence and rather enhance their level of independence.

It was found out that as many as 79% of the women studied were able to share ideas with their spouse; 7.5% of them said they were able to express their views on family planning; 75% could give instances of the type of decisions that they were able to take in the home. About 94% of the women were involved in the planning of their family’s budget, 90% were able to decide on their own to hand over their properties to their heirs, 83% were allowed by their husbands to decide on how to use their money, and 97% of the women who were able to share ideas with their spouses had their views taken into account. Again these results show that the women had high participation in decision-making in the home. There were however a few lapses which would require capacity building to improve upon their situation.

From the study 71.6% of the women were allowed to express their views in public; 71.6% of the women were invited by elders when discussing issues of the community; 74.3% of the women who had the chance of expressing their views reported having had their views accepted, and 66.1% of the women belonged to a women’s association, with 65% being able to mention the benefits that they derived from the associations. Based on these results it could be observed that the women had high participation in decision-making in the community. However there is the need for improvement to enhance both those women who had the chance of participating in decision-making and the few who seemed not to be involved in decision-making at all.

Considering the fact that empowerment is a broad concept, there could be a constraint of the study being limited to only the education, economic and decision-making aspects of empowerment. However the results throw a challenge to Adult Educators and other change agents to undertake and intensify capacity-building and human development activities to improve the women’s level of empowerment.

It can be deduced from the findings of the study that, although the women had generally attained an averagely high level of empowerment there is still more room for improvement in the areas of education, the economy and decision-making in the home and the community. The women’s skills need some sharpening so that their level of empowerment could be enhanced.

To achieve this Adult Education becomes an essential tool since education has been seen as the foremost agent of empowerment. Pomary (1992:21) says that

“no matter how we run away from it, the foremost agent of empowerment is education: education is the only passport to liberation, to political and financial empowerment. Education contributes to sustainable development. It brings about a positive change in our lifestyles. It has the benefit of increasing earnings, improving health and raising productivity.”

This makes adult education crucial in the women’s empowerment process.

Adult education has been briefly described in the Encarta Reference Library (2005) as: All forms of schooling and learning programs in which adults participate.

It is further explained in the Encarta Reference Library that unlike other types of education, adult education is defined by the student population rather than by the content or complexity of a learning programme. Adult education could therefore mean any teaching- learning activity organized for adults irrespective of mode of delivery, content or level. It includes both formal and non-formal educational programmes like university credit programmes, literacy training, community development, on-the-job training, and continuing professional education. Programmes vary in organization from casual, incidental learning to formal college credit courses. Institutions offering education to adults include colleges, libraries, museums, social services, government agencies, businesses, non-governmental organizations, churches etc.

To give a brief background of the development of adult education, it is explained in Encarta (2005) that early formal adult education activities focused on single needs such as reading and writing. Many early programmes were started by churches to teach people to read the Bible. When the original purpose was satisfied, programmes were often adjusted to meet more general educational needs of the population. Libraries, lecture series, and discussion societies began in various countries during the 18th century. As more people experienced the benefits of education, they began to participate increasingly in social, political, and occupational activities. By the 19th century, adult education was developing as a formal, organized movement in the Western and developing worlds.

A person’s desire to participate in an educational programme often is the result of a changing personal, social, or vocational situation. This individual orientation has resulted in the creation of a continually changing, dynamic field able to respond to the varied needs of society. Recognizing the need to update information and skills, the desire for knowledge and information is also increasing among women. Rapidly changing technical fields also require constant updating of information in order for workers to remain effective and productive.

As explained in Encarta, another major development is the increasing use of radio, network television, and cable television for adult education; broadcast media are being used worldwide to provide public information, teach reading and writing, specialized seminars, and short courses, as well as to provide university degree programmes. These electronic media offer the means for reaching populations that are homebound or geographically isolated like rural communities.

In Ghana as a result of the limited educational opportunities in the formal school system, voluntary adult education associations emerged as far back as the 1830s. These associations engaged in discussions and implementation of literacy programmes to keep abreast of the times and improve upon their educational standards. Some also wanted further studies for promotion and salary increment. Through this process adult education in Ghana has progressed to the university level to provide both formal and non-formal education to the masses (Amedzro, 2004). The Non-Formal Education Division (NFED) is the government machinery for delivering basic adult functional literacy. Launched in 1991, the National Functional Literacy Programme has undertaken several activities to accelerate reduction of illiteracy in the country to facilitate rural and national development.

A report by the NFED on the celebration of the International Literacy Day, 2005, specifies that the National Functional Literacy Programme provides reading, writing, numeracy, and an enabling environment for learners to acquire income-generating skills by establishing income generation projects and classes. Leaders of these projects are trained in entrepreneurship, management, book keeping, fund sourcing and marketing skills. Beneficiaries are trained in cassava processing, kente (a local royal cloth) weaving, batik and tie-dye making, beekeeping, baking etc. There is also an English literacy programme that aims at expanding the learning scope of learners to build their public communication skills. Over the period of operation, the NFED’s achievements include an annual average intake of 200,000 learners, a total recruitment of 2,505,709 and a total of 1,669,210 graduates of the programme. Its community development achievements include provision of drinking water, child day care centres, classrooms and market sheds. Some learners have also graduated into the formal educational system through to tertiary level. Others have also taken responsible roles in the communities to serve as Traditional Birth Attendants, religious leaders, District Assembly persons and Unit Committee chairpersons (NFED, 2005).

Not only in Ghana, Encarta (2005) explains that adult education has long been important in Europe and other parts of the world, where formal programmes began in the 18th century. For example, the Danish folk high school movement in the mid-19th century prevented the loss of Danish language and culture that a strong German influence threatened to absorb. In Britain, it is reported that concern for the education of poor and working-class people resulted in the growth of adult education programmes, such as the evening school and the Mechanics’ Institutes to expand educational opportunities for all people. After the Russian Revolution the Soviet government virtually eliminated illiteracy through the establishment of various institutions and extension classes for adults. In other parts of the world adult education movements are of a more recent origin. In 1960, Egypt established a “schools for the people” system designed to educate the adult population. After many years in which the primary educational concern was with creating public school systems, in the 1970s countries in Africa, Asia, and Latin America began to increase opportunities for adult education. Innovative programmes involving the mass media are being used in many countries. Tanzania, for example, has used mass-education techniques and the radio to organize national education programmes in health, nutrition, and citizenship.

A literate population is a necessity for any nation wishing to take advantage of modern technological growth. Research has shown a direct relationship between literacy among women and improved health and child care in the family. The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) has long supported the concept that education must be considered an ongoing process. UNESCO has encouraged literacy programmes, agricultural extension, and community instruction. It is in the light of this that adult education becomes crucial for facilitating empowerment among women.

From the study it was realised that 32.8% of the women had no formal education at all, while 44.8% had completed their formal education at the basic level (Primary, Junior Secondary and Middle School). Only 1.6% had completed Training College education and 17.5% had been schooled up to the secondary school level. As a result of their low level of education the women engaged in small-scale businesses in the informal sector like farming, petty trading, brewing of local drinks, shear-butter extraction etc., in order to get an income for survival. Only 3.3% of the women were in the civil/public service. Due to the inconsistent and low-profit making nature of their jobs 56.3% of the women did not have a regular source of income. To some extent the women’s low level of education had also affected their chances of sharing their views in public and having their views being taken into account. This implies that the women need some skill training to improve upon their income-generating activities, functional literacy programmes to upgrade their reading and writing skills, awareness creation programmes in general and access to public information to make them more enlightened. With this sort of capacity building and human development activities coupled with some incentives for higher productivity, the women’s capacity could be enhanced.

Specific adult educational activities for the different areas of study to facilitate the women’s empowerment process could include the following:

Education – noting that 32.8% of the women studied had no formal education at all, it becomes crucial to promote female education. The female youth of the community could be counselled, encouraged and given the necessary assistance to go through formal education to a higher level so that they will become well equipped to operate in higher competitive productive activities. Similarly, functional literacy programmes for the female adults will help improve their reading and writing skills. Obviously such skills will further enhance the women’s access to public and educational information. The use of information technology like radio, internet, and handheld devices will help reach those in remote areas. Recent studies have shown that women are willing to pay for such services.

Decision-making in the community – recognizing the influence of men in society and on women, opinion leaders – who are mostly men – could be informed to encourage or motivate more women to express their views in public so that they could as well contribute to the development of their communities. In addition to the queen- mother position, women could as much as possible be given key positions among the elders in the traditional, political and other decision-making institutions. In this case it will be useful to equip women with leadership skills for effective participation in all levels of decision- making and governance in their various communities.

Various religious organizations could also encourage women to get involved in the religious associations and other interest groups that undertake educational activities to facilitate their processes of empowerment.

Decision-making in the home – as much as possible it will be useful to encourage communication among couples. Husbands will have to be counselled and given the orientation to respect the views of their partners no matter how irrelevant and provoking they might be so that women will be able to build their confidence and express their views. It will be helpful for husbands or men to consult wives or female colleagues on family issues rather than taking decisions on their behalf. Giving women room to operate will help them to gain a high level of independence and confidence. Above all cordiality among the family and community members will enhance morale.

Economic empowerment –towards achieving or promoting economic empowerment among women, it will be crucial for change and development agents to organise training for them in farming and other small scale businesses to be able to acquire more skills to enhance their careers.

Traditional authorities could also manage to remove the traditional inhibitions which prevent women from getting equal access to land for agricultural purposes.

Incentives like credit facilities, modern technology for higher productivity, extension services and other assistance will have to be made available to women so that they could improve upon their production and be able to acquire enough capital and a regular source of income as well.

In addition women will have to be encouraged and educated to engage in banking transactions other than the ‘susu’ (saving money with unauthorized individuals) means of saving money so that they could benefit from incentives like loans from banks. If women are not comfortable with the bank’s formalities, the bank will have to be brought to the level of the women.

Adult education aims at improving the situation of people by increasing their skills, knowledge and awareness. The survey on the women of Mo communities of Ghana helped to assess their educational, economic and decision-making levels. Though the study revealed a high level of participation in decision-making in the home and community and economic independence, about 32.8% of the women had no formal education at all, 44.8% had completed their formal education at the basic level (Primary, JSS and Middle School), only 1.6% had completed Training College education and 17.5% had schooling up to the secondary school level. As a result of their low level of education the women engaged in small-scale private businesses like farming, petty trading, brewing, shear-butter extraction etc., in order to get an income for survival. Only 3.3% of the women were in the formal sector. Due to their dominance in the informal sector and the inconsistent nature of their jobs 56.3% of the women did not have a regular source of income. Adult education therefore becomes crucial to enhance the women’s capabilities to be able to organize themselves, to improve their skills for generating income, to increase their own self-reliance, to assert their independent right to make decisions or choices and to be able to control resources which will assist them in challenging and eliminating their subordination.

References

Advocates for Gender Equity (AGE) 2000) Report on Mapping, Exercise on Gender Activities in Ghana, Accra.

Amedzro, A. K. (2004) in Asiedu et al (Eds) The Practice of Adult Education in Ghana. Accra: Ghana Universities Press.

CODESRIA (2005) 2005 Gender Symposium www.codesria.org (DA: 09/09/05). Encarta Reference Library (2005) Microsoft Corporation. Ghana-Canada In-Concert (2000) Programme Document. Karl, Marilee (1995) Women and Empowerment: Participation and Decision-making London: Zed Books Ltd.

Moser, Caroline O.N. (1993) Gender Planning and Development: Theory Practice and Training London: Routledge.

NCWD (1994) The Status of Women in Ghana (1985-1994) National Report for the 4th World Conference on Women, Accra.

NFED (2005) Non-Formal Education Division – Celebration of International Literacy Day, Daily Graphic of Ghana, Friday, September 9th 2005.

Rowlands, J.O. (1998) A Word of the Times, but What Does it Mean? Empowerment in the Discourse and Practice of Development in Afshar Haleh (Ed) Women and Empowerment: Illustrations from the Third World, New York St. Martin’s Press Inc.

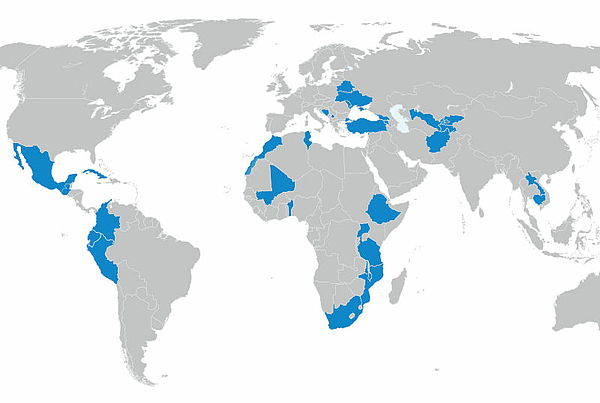

DVV International operates worldwide with more than 200 partners in over 30 countries.

To interactive world map