Ehsanur Rahman

Genokendra is the Bangladeshi word for people’s centres. The main objective is to establish opportunities for Lifelong Learning and community development. This paper describes the process of how community learning centres have evolved in Bangladesh and how, over the years, they have become, for the people in the community, a forum which supports their learning needs and therefore contributes to social development. The field-based experience of Dhaka Ahsania Mission (a Bangladeshi NGO working both nationally and internationally) has been largely used in this paper as case-based on the experiential learning of the author. Ehsanur Rahman is the Executive Director of the Dhaka Ahsania Mission and a member of the UNESCO resource team. He is a key person in formulating and translating the concept of community learning centres (CLC) in Bangladesh and other countries.

Ganokendra – People’s Forum for Lifelong Learning and Social Development

The Bangladesh Experience

Historically, the concept of Lifelong Learning is embedded in the development proc ess of civilization. The cradle-to-grave perspective of learning is widely known and promoted in many countries. With the passiva of time and the diverse learning needs of the people, the concepts and forms of learning and education become wider, though the basic spirit of the need for continuity in learning remains.

In the present context, Lifelong Learning is seen as a process that involves pur posive and directed learning. Each individual sets a series of learning objectives and then pursues these by the means available in society. But making a conscious commitment to Lifelong Learning and being willing to take full advantage of the learning opportunities of a society requires that people become autonomous learners. Lifelong Learning thus promotes autonomy of learning among the citizens as a measure to sustainable social development.

Social development refers to a process of organizing human energies and activities to achieve anticipated results. Social development increases the utilization of human potential (Garry Jacobs and Harlan Cleveland, 1999) and improves the capacity of society to fulfill its aspirations, gradually resulting in the transformation of social structures. In this process, changes in the quality of life for people are expected more than material gains.

The global call of Education For All (1990) and the Dakar Goals (2000) with emphasis on access to quality education by all age-groups provoked many countries across the globe to explore various innovative practices. A key element that was learned and that is common across the regions is that, the more the community plays pro-active roles in planning and managing educational activities, the more the educational interventions meet the learning needs of the people and the initiatives become sustainable. Organizing Community Learning Centres (CLC) as centres for Lifelong Learning is such an approach which evolved in the Asia-Pacific region with active participation of the communities in the countries of the region, with support from government and non-government organizations, and technical support from UNESCO Bangkok. With its strategic focus in facilitating Lifelong Learning and social development, it was found that the CLC, as an approach, has replication potential in other regions.

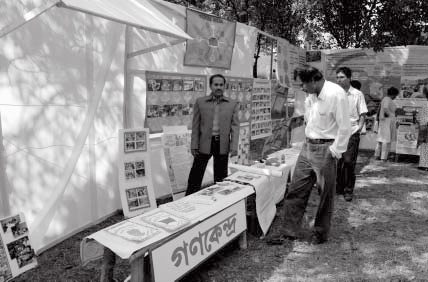

Discussion with policy makers

Source: Ehsanur Rahman

Context Bangladesh

All citizens of Bangladesh have a constitutional entitlement to basic rights, and to fulfill these obligations to its citizens the government departments provide a range of essential social services through their designated field offices. In addition to gov ernment services, numerous non-government and private initiatives exist throughout the country offering basic services such as education, health, agriculture and liveli hood services particularly to the poor communities. However, the vast majority poor and vulnerable people, especially women, children and people with disabilities, have little or no effective access to these public resources, services and informa tion. Many of them are not even aware of their rights and consequent entitlements to the available local social services, because of their illiteracy, ignorance and unorganized voice on their entitlements. As a result, they have little or no voice in local decision-making processes or the local level planning and management of these services. An immediate consequence of this ist hat the rural poor seldom have access to these services or even the information about the services.

The coverage and system of literacy and post-literacy programs in the country is also inadequate to provide support to the people with limited reading skills to continue education. Without adequate provision for retaining the newly acquired literacy skill by the illiterates and school dropouts, the danger of losing much of the impact of acquired literacy skills is always there. One of the devices to retain the literacy of the neo-literate, particularly the adolescents and the adults, who do not intend to enter into the formal system of education, is organizing multi-purpose community learning centres at the doorsteps of the neo-literate poor population. From this perspective, the Ganokendra (peoples centre) approach of Dhaka Ahsa nia Mission in Bangladesh is analyzed as a model at the community level offering opportunities for continuous updating of knowledge and Lifelong Learning.

A number of initiatives have been taken in Bangladesh by the NGOs and relevant government departments to ensure literacy practice of the neo-literate. These include village library, box library, village study circle, and Ganokendra. Village level libraries are organized either by the sponsoring organizations or by the local people, where books and other materials are collected from different sources. The neo-literate has access to these libraries and can come regularly and borrow books for reading. Box library has been introduced as an indigenous type of library. Books are kept in a box (metal or wooden) under the care of a volunteer in the literacy cen tre. (S)he issues books to the learners according to their reading skill and organizes group reading or individual reading by them. The volunteer provides them back-up support in overcoming difficulties in reading. In the Village Study Circle, necessary support is provided to the neo-literates to continue their education and put it into practice. Special kinds of reading and writing materials are supplied for discussion in the Village Study circle. Analysis of these post-literacy programmes shows that the post-literacy programmes are offered mostly on an ad hoc or short-term basis; there is a general lack of institutionalization of post-literacy activities.

Ganokendro Model of CLC as a People’s Forum

The literal meaning of the Bangla word Ganokendra is people’s centre. The general objective of organizing a Ganokendra is to create facilities for Lifelong Learning and community development. On the initiative of Dhaka Ahsania Mission (DAM), Ganokendra are organized to facilitate institutionalized support for the people in the community towards improvement of quality of life, social empowerment, and economic self-reliance. Based on the organizational learning of DAM over many years and collaborative activities with UNESCO in achieving EFA Goals in the Asia-pacific region, DAM worked persistently to develop a contextually appropriate CLC model, which gradually become branded as Ganokendra.

DAM’s literacy programme for rural adults began in 1984, while the post-literacy programme dates from 1986. The initial post-literacy programme was aimed at providing short-term back-up support to neo-literates because there was a dearth of reading materials in the rural areas. To provide a structured post-literacy pro gramme, in 1992 DAM initiated Ganokendra as a post-literacy major function; gradually the role was widened to meet the learning needs of the community in other fields. For example income generation activities were added in 1995, supplemented by skills training and micro credit, water and sanitation activities were added in 1997, and anti-drug and anti-tobacco activities in 1998. With the increase of the incidence of trafficing in children and woman, particularly in the border districts in the western part of the country, child and women trafficking awareness activities were added in 2000. Ganokendra now play the role of village community centres with libraries and facilities for recreation and other socio-cultural activities. The community also uses the centre to hold regular discussions on issues of local interest.

Over the years, with the expanded functions of Ganokendra, there is an in creased role for the community in sharing management responsibility. Gradually, linkage has also been established with various development agencies at local level according to the people’s needs. Networking among the people’s centre at Union (lowest administrative tier) is developed through establishing a Community Resource Centre (CRC) for interaction and exchange of experience, which functions as an advocacy platform for dialogue with Union Parishad (local government) and other institutions. Ganokendra is now considered as:

- A meeting point for the community, particularly for disadvantaged people.

- A community organization to cater to diverse learning needs of the community.

- A platform for community interaction and participation in social, economic and cultural activities for sustainable development.

Community Meeting

Source: Ehsanur Rahman

Features of Ganokendra

Ganokendra addresses the learning needs of local people, particularly the neo literates, from a Lifelong Learning perspective. The users of Ganokendra gradu ally strive to reach advanced learning level through various education packages. Ganokendra is accessible to all people in the area, not just the neo-literates from literacy centres. Out-of-school children, people with limited reading skills, school dropouts, students, farmers, parents, community leaders. It is used as a place for training and issue-based discussion and its activities are linked with socio-economic and environmental programmes. The Ganokendra also functions as an information centre where newspapers, newsletters and information materials from other agen cies are available. At certain points, it is used as a service delivery centre by other agencies including government extension departments.

As a centre to promote Lifelong Learning, Ganokendra meets diverse learning needs of the people in the community. Types of learning materials vary, covering textbooks for children, adolescents, and adults, graded post-literacy materials and continuing education materials. Variety also exists in the format of educational materials – book, chart, card, poster, game, newsletter, and wall magazine, folder, leaflet, puzzle, sticker, CD and video. There is a variety in contents of learning materials, covering issues like, water and sanitation, gender, life skills, income generation, health and nutrition, HIV/AIDS, drug abuse prevention, population, culture, human rights, child and women trafficking prevention, environment, etc.

Ganokendra Functions

Ganokendra functions are broadly divided into four types: Educational activities, Information networking, Social empowerment, and Economic development.

The educational activities include a literacy programme for adults and adoles cents, life skills education, non-formal education for out-of-school children and development of educational materials based on local needs. To make educational activities effective, educational networks among the Ganokendra in a particular area have been developed. The following are few examples of networking and partnership of Ganokendra:

- Networking of all Ganokendra in a Union for exchange of materials and training.

- Linkage with local formal schools to facilitate continuing education for primary education graduates.

- Linkage with Bangladesh Open University to facilitate secondary distance education.

- Facilitation of vocational skill training for income generation through partnership.

- Networking with Primary Schools for increased enrollment, reduced dropout and quality education.

To facilitate people’s access to information, a series of information networking functions are performed in the Ganokendra. It functions as a community-based information centre of local GO-NGO extension departments; it promotes exchange of information through newspapers, facilitates exchange of experience, dissemina tion of success stories and innovations at the local level.

Community Resource Centre (CRC) – local level network of Ganokendra functions as an advocacy forum, for having dialogue with Union Parishad and other service agencies. At the CRC level, there is scope for use of ICT for interactive information communication. As the networking forum of Ganokendra, CRC offers a number of services contributing to Lifelong Learning and community development. The fol lowing are a few examples:

- Information services, through news bulletins, wall magazines.

- Services for market linkages providing information about products and price.

- ICT/Tele centre services, e.g., phone, computer compose, printing.

- Recreational activities like arranging sports, film show, competitions.

- Documentation of learning and exchange of experiences.

The social empowerment functions of Ganokendra are largely aimed at community capacity building to claim quality services by the people for which they are entitled. At the local level, the following approaches are generally pursued by Ganokendra or CRC towards people’s empowerment.

- Discussion sessions on social issues.

- Organizing action groups to prevent social vices.

- Facilitating social harmony/peace, including use of Ganokendra or CRC as venue for social interaction and conflict resolution.

- Promotion of indigenous knowledge and local wisdom.

The economic activities of Ganokendra are particularly aimed at supporting the poor people to generate increased income towards improving their living condi tions. Need based economic activities are planned at the local level. Few common activities are mentioned below:

- Supply of books and manuals on income generation activities.

- Skills and enterprise development training.

- Credit support and/or facilitating linkage with credit institutions or programmers.

- Technical support for quality products.

- Supporting market linkages.

Ganokendra Management

Ganokendra are organized and managed by the groups of users in collaboration with the local community and back-up support from DAM. The overall management is the responsibility of the management committee consisting of people in the local ity. There is direct or indirect support from local government bodies and community leaders in program planning and management. Local people, exiting and potential users of the Ganokendra are consulted in the process of formation of the manage ment committee. The committee is equipped to develop plans for the activities that the center is to undertake (for example, training courses, networking activities, resource mobilization, etc.) and to ensure that the activities are implemented as per plan. One manager for the Ganokendra, commonly known as Community Worker (CW), is recruited from the community. The CW initiates the activities and looks after the smooth functioning of the centre. (S)he is responsible for the overall operation of the Ganokendra/people’s centre. The tutors required are also recruited from the community by the committee. The CW and the tutors share the responsibilities of maintaining the library, information center, collect books and materials, organizing social mobilization activities.

The community people contribute land, manual labor, money, material to es tablish the Ganokendra/peoples centres. The members of Ganokendra provide subscription on regular basis. The members save their small savings in a bank account in the name of Ganokendra. The committee distributes the fund as a small credit among the members with a reasonable interest rate. Sometimes, the com mittee takes special initiatives to collect seasonal crops from the members or other people in the community to generate fund. The well-off people (philanthropists) and the representatives of the local government provide funds to undertake activities. DAM provides matching funds on occasions and supports new initiatives.

Achievement and Impact

Over the years, along with the functional expansion of Ganokendra roles, there has also been geographical expansion of organizing across Bangladesh. The study on DAM Ganokendra (2009) shows that starting with 20 Ganokendra in 1992, as of December 2009, there were 753 Ganokendra in operation spread over in 87 Unions of 5 Districts. Of these, 50 have been phased out as self-supporting centres and 262 more Ganokendra are in the phase out process. Additional 2472 centres were in the process of institutionalization as CLC which are spread over in 151 Unions of 23 Districts.

Another study report (2003) shows that Ganokendra could demonstrate visible effects on literacy. Literacy rates in the area increase and literacy competency of adults become consolidated. It says, “75 % of neo-literates had scored above the minimum in standard tests, reading and life skills are substantially better than writing and calculation skills, and a significant portion of women members could perform tasks assigned confidently”. As a result of access to information, it was found that there was an increase in proper sanitation practices that contributed to reducing the number of illnesses in the community; government officials from the departments of youth, social services, agriculture, women and children affairs, etc. were often tapped to provide basic health care. In social awareness and survival skills, changes are found in the capability to express thoughts in writing, adoption of family planning practices, attitude towards/rejection of dowry system, women participation in community activities. Access to the market and the world of work has been facilitated to “have enhanced what people were already engaged in to create added value”. Ganokendra effectively helped people to manage their small enterprise better, have taught people new skills and helped people to correct mistakes and maximize opportunities along the way.

The ultimate contribution of Ganokendra is strengthening of the access of the poor people to human, natural, financial and social assets as well as economic and social services, thus facilitating taking leadership responsibility for particular activities. From an empowerment perspective, it can be concluded that changes have been observed in areas of awareness as well as application knowledge and skills, changes in attitudes and behaviour both at the household level and the community level.

Women group meeting

Source: Ehsanur Rahman

Replication of the CLC approach and Potentiality

The initiatives for replication of the CLC experience at the national, regional level, and cross-regional level proves that CLC have the potentiality of replication as a strategic approach to facilitate Lifelong Learning and social development. In this section, lessons from a few such initiatives are cited, where DAM shared the experience and highlighted key generic strategies of organizing and operating CLC.

In Bangladesh, jointly by UNESCO and DAM, lesson sharing and joint planning workshops have been organized with participation of some NGOs and govern ment agencies to explore the possibility of establishing community-based networks of learning centres in line with the non-formal education policy and based on the lessons from various forms of CLC in the country, including Ganokendra.

The Bangladesh experience of Ganokendra and its consequential positive impact on female literacy rates encouraged DAM Pakistan (DAMP) to go for replication of the model in Pakistan, beginning with the Barakahu Union Council as its pilot project area. DAMP has established one CLC-based vocational center and three Early Childhood Care and Education (ECCE) centers in Shahdra Khurd, a village located in Barakahu.

In 2007 and 2008, UNESCO Rabat and UNESCO Bangkok jointly commissioned a mission to provide technical support to Morocco in organizing CLC. Based on the Asian experience, through this technical support and collaboration, four CLCs have been organized in four remote villages of Morocco by local partners. A follow-up mission after a year shows that the CLCs facilitated more solidarity in the community enabling people to know each other better; the communities made CLCs an attractive place for people to get together to solve the local problems.

UNESCO organized a workshop in 2009 jointly with the Okayama University (Japan) and the Ministry of Education, Culture, Science and Sports of Japan, to share the global, regional and sub-regional views and dialogues on ESD (Education for Sustainable Development) and CLCs as a measure to develop a framework for promotion of ESD through CLCs.

The Sixth International Conference of Adult Education (CONFINTEA VI) of Belém, 2009, Call for Action, identified a number of action areas for “harnessing the power and potential of adult learning and education for a viable future”. In the Belém declaration this is a specific recommendation “to create multi-purpose community learning spaces and centres” to improve access to and participation in the full range of adult learning and education programmes. As a follow-up to CONFINTEA VI, the Japanese National Institute of Education and Research or ganized a seminar in February 2010 to facilitate the exchange of experience of Japanese CLC (Kominkan) and promoting the concept of CLC globally. A number of measures for collaborative actions were worked out during the seminar.

Meeting of people’s organizations

Source: Ehsanur Rahman

References

Beyond Literacy – Ganokendra – A book published by Asia South Pacific Bureau of Adult Education (ASPBAE), India (2000).

Ganokendra: The Innovative Intervention – published in the Handbook on Effective Implementa tion of Continuing Education at the Grassroots by UNESCO Principal Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific, Bangkok (2001).

Innovation and Experience in the Field of Basic Education in Bangladesh – published by Campaign for Popular Education (CAMPE), Bangladesh (2000). UNESCO published a case study in their The New Courier, April 2003 issue under the title Literacy in Communities – Village Revolutions (the case of Hira, a beneficiary woman).

Strategic Evaluation of Community- based Development Interventions of Dhaka Ahsania Mission (May, 2003) initiated by the major financing organization of the programme – CORDAID of the Netherlands. Three international consultants (Jowshan A. Rahman, Arnold Vanderbroek, and Mirza Najmul Huda) undertook the evaluation.