Shermaine Barrett

Shermaine Barrett

University of Technology

Jamaica

Abstract – How can we build the capacity of adult educators to create inclusive classes within the context of student diversity? This article outlines a process through which adult educators can develop a better understanding of themselves in terms of their values, moral perspective, biases and prejudices and identify how these traits influence their interactions with their students. The assumption is that reflexivity, the willingness to self-reflect, enables instructor self-knowledge, which leads to better self-management and context management, resulting in turn in being better able to create an inclusive learning environment.

Living in an ever-changing and connected global world, diversity has increasingly become a hot topic in political, legal, corporate and educational arenas. As a concept, diversity acknowledges that people differ in many ways, some visible, some invisible. Typical examples include age, gender, marital status, social status, disability, sexual orientation, religion, personality, ethnicity and culture.

Gardenswartz and Rowe (2003) categorise these multiple dimensions of diversity in what is called the Four Layers of Diversity model. In this model, the four layers are depicted as four concentric circles. Moving from the centre outward, these layers consist of personality in the centre, internal dimensions in the second circle, external dimensions in the third circle, and lastly organisational dimensions in the fourth and outer circle. The personality dimension relates to the individual’s personal style and characteristics, which speaks to whether an individual is an introvert or extrovert, reflective or expressive, a thinker or a doer. In the second layer, the internal dimensions speak to those characteristics over which the individual has no control. These include characteristics such as gender, age, race, sexual orientation, ethnicity and physical ability. In the third layer, the external dimensions comprise those aspects that are the result of life experiences and choices such as religion, educational background, work experience, parental status, marital status, recreational habits, geographic location and income. The fourth layer, the organisational layer, consists of characteristics such as work content/field, management status, union affiliation, seniority, work location, divisional department, and functional level classification. The characteristics of diversity associated with this layer are items under the control of the organisation in which one works.

All the dimensions discussed by Gardenswartz and Rowe (2003) are important in adult education. Wherever in the world we are, the issue of diversity is central to the adult learning classroom. Such classrooms comprise a range of ages, multitude of beliefs, understandings, values, ways of viewing the world, as well as the diverse experiences of the participants. In some regions, the issue of diversity is further compounded by the recent spate of mass migration as people flee political and social unrest in their homelands to seek protection and assistance in other countries. These people will need education and training on many levels as they seek to integrate into their host countries.

Adult education is also usually associated with efforts to address issues that people face in their communities – for example issues of poverty, ill health, crime and violence, political disempowerment, exclusion of individuals based on gender, class and other factors, the need for work skills, and environmental degradation. The role of education is therefore twofold. It should lead to a better, more fulfilling personal life, but at the same time should result in a better citizenry and a better world. For that to work, learners must be empowered and included. Learning is therefore best facilitated in a context of mutuality and respect in which participants feel valued. A typical trait in adult education is that a high degree of participation is expected from everybody. This includes learners taking responsibility for their learning and engaging in open and authentic dialogue within the learning environments. Within the classroom, healthy forms of communication and freedom to critique and choose is facilitated, and students’ initiative and autonomy are promoted (Barrett 2012).

Given the context and the goal of adult education, adult educators should actively manage and value the diversity within their learning spaces to ensure that learners feel included within the learning environment. The adult educator has to move from simply acknowledging and accepting that individual learners are different, to a position where he or she creates an atmosphere of inclusion. The key to creating an inclusive classroom that encourages participation, teamwork, and cohesiveness is diversity management which encourages persons to interact and share ideas. Instructor competence in creating inclusive classrooms through diversity management is of vital importance here.

Let us now take a closer look at a number of strategies that will help adult educators develop the competencies to create inclusive classrooms. Our starting point is that educators who develop a reflexive practice are best able to create inclusive classrooms where participants feel respected, their views are honoured and therefore they feel free to participate.

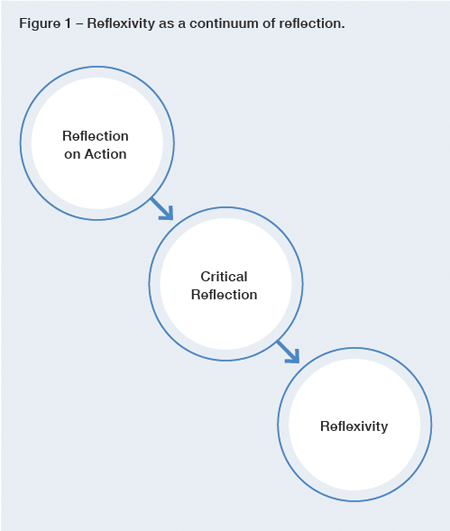

Reflexivity refers to the teacher’s willingness to explicitly examine how his/her assumptions, personal beliefs, and dispositions impact his/her attitude towards teaching and students and their consequent willingness to look at things from a different perspective (Barrett 2012). Reflexivity requires the individual to think more critically about their actions and to question how they see their world. It gives focus to the presuppositions, assumptions, values, personal philosophies, the things we take for granted and their impact on our relationships. This form of reflection is identified by Mezirow as premise reflection, that is, reflection on questions about why we behave the way we do; “what is it about the way we see other people that compels us to make polarised, summary value judgments” (Mezirow in Welton 1995: 45). The practice of reflexivity involves questioning the relationship between one’s self and others (Cunliffe 2004). It exposes contradictions, doubts, dilemmas and possibilities (Hardy & Palmer 1999). Reflexivity, with its focus on self-reflection, has profound potential for major personal transformation at the level of what Mezirow (1997) describes as the transformation of one’s meaning perspectives. Reflexivity may be seen as one aspect of the larger field of reflection, and as such may be viewed as progression along a continuum, moving from reflection on action and in action (Dewey 1933; Schon 1983), to critical reflection (Stephen Brookfield 1995), and then to reflexivity or transformational learning (Mezirow 2000). (See figure 1).

A reflexive practice requires that the instructor engages in reflection at various stages of his or her practice. The literature on teacher reflection speaks to reflection before, during and after instruction. Dewey (1933), Schon (1983) and Laughran (2005) all spoke to reflection from the perspective of timing when they referred to reflection as reflection-for-action; reflection-in-action and reflection-on-action. Reflection-on-action (Dewey 1933; Schon 1983) refers to looking at situations retrospectively and seeking to see how they could have been done differently. It entails a systematic and deliberate process of thinking about one’s actions after an event. Reflection-in-action refers to thinking about doing something while doing it. This type of reflection may be described as thinking on your feet. It occurs when an individual reshapes what he or she is doing while doing it. Mezirow (1995) described reflection-in-action as the momentary kind of reflection that is used in an immediate situation to guide next steps.

Key to reflection-in-action is past experiences that allow one to recognise the kind of response that a particular action is likely to evoke, leading to a modification of one’s actions. This type of reflection can be aligned with the notion of self-management promoted in the literature on emotional intelligence. Reflection-for-action is anticipatory in nature. This refers to reflection that takes place prior to an experience, and as such may be described as reflection for action. The focus of this form of reflection is self-awareness, another central notion of emotional intelligence. Creating inclusive adult classrooms requires that the instructor engages in reflexive practices before, during and after the learning experience.

Teaching in contemporary societies takes place in complex and diverse settings. Nowhere is this truer than in the adult learning classroom, given the heterogeneity of those classrooms. The educator can be called a teacher, tutor, facilitator, or guide. Regardless of the title, he or she needs to create and manage a classroom environment that facilitates all students’ learning. What the educator does or does not do is of great importance in facilitating learning. At the same time, the nature and outcomes of our behaviours as teachers are largely impacted by our intellectual assumptions, beliefs and emotions. Teachers respond to students based on their thoughts, worldview, values and assumptions. Thus, sometimes “what we think are democratic, respectful ways of treating people can be experienced by them as oppressive and constraining” (Brookfield 1995: 1).

Reflexivity provides a tool that makes teachers aware of the lenses they wear as they teach and through which they view their classrooms. But it also acts as a mirror that enables the teacher to view him or herself and to make explicit that which is tacit or taken for granted. In so doing, being reflexive helps teachers to clarify and redefine their educational beliefs, images, and assumptions, and enables them to see how their conclusions about events in their classrooms are really just their interpretations of such interactions. The reflexive process enables teachers to integrate their professional beliefs and theoretical knowledge into new professional meanings and concrete practices for the benefit of creating and maintaining inclusive classrooms and to ensure student learning. Village and Lucas (2002) observed that teachers are better able to create a more effective communication with their students when they know their students’ cultures, confront their own prejudices and behave unbiasedly. Reflexivity therefore facilitates the development of the teacher’s personal and social competence – emotional intelligence – and facilitates transformative teacher growth. This helps the teacher to be less emotional in the classroom, thus creating a friendlier learning environment.

Teaching adult educators to be reflexive begins with instructors clarifying their core values, developing a vision, and consciously aligning their attitudes and beliefs with their actions and behaviour.

Avery and Thomas (2004) noted that courses that mainly lecture with little learner interaction and experiential learning are unlikely to increase diversity awareness. Active engagement and experiential activities help learners make the transition from cognitive knowledge of concepts to a more thorough understanding and practical applications. Consequently, the strategies to promote reflexivity in adult educators presented here are fundamentally experiential and participatory. The strategies are theoretically grounded in the ideas of critical reflection (Freire 1995), transformational learning (Mezirow 1997), experiential learning (Kolb 1984; Jarvis 2010), social constructivism (Vygotsky 1978) and reflective practice (Brookfield 1995; Loughran 2005; Mezirow 1997).

The four strategies presented are recommended for use in either a pre-service instructor training context, or in-service instructor training. All the strategies allow instructors in training to actively participate in structured learning experiences, either individually or in groups. These strategies create learning experiences, either real or simulated, to facilitate the individualʼs own self reflection/introspection. The aim therefore is not to directly teach, but to allow the instructors as learners to discover information about themselves through self-reflection and group interaction. In the sections that follow, the adult educator in training will be referred to as the trainee, and the teacher will be referred to as the instructor.

Journals are tools that promote growth among trainees through critical reflection and meaning making. The goal of journal writing is for students to evaluate their actions and reflect on how they could handle a situation differently in the future – reflection-on-action. But it also facilitates reflection-for-action, as the result of the analysis will inform future actions. Journal writing provides a safe place for free expression of thoughts and feelings. Reflective journaling provides guided opportunities for learners to “think aloud” on paper and reflect on their own perceptions or understandings of the situations encountered (Brown and Sorrell 1993). Trainees are able to describe why decisions were made and actions taken, along with feelings and future thoughts and directions.

As a strategy for teaching reflexivity, trainees would document incidents in which they recall being challenged by a student or a differing view, or feeling uncomfortable or angry within the learning space. They would be asked to analyse their responses within those situations. The instructor would then provide one-on-one feedback to the trainee about their journal entry. The feedback should be devoid of judgment and criticism. Rather, feedback should serve to challenge the trainee to reflect on his or her experiences and to push the trainee to reflect more deeply at the level of their assumptions, presumption and beliefs about him or herself, their learners and the learning environment. This includes pushing trainees to continuously ask themselves why a decision was made or why they feel the way they do about a topic or a situation. To be effective, the journal writing process should be well planned and have explicit student expectations. Additionally, trainees will need to be open-minded and willing to take responsibility for their actions in the various incidents recorded.

© Nhung Le

The aim here is to expose biases, prejudices and personal concerns. The effectiveness of this approach rests on the willingness of the trainees to be open to rethinking their assumptions and to subject those assumptions to a continuous process of questioning, argument and counter argument. The adult educator in training also needs to be objective in presenting and assessing reasons for positions and reviewing the evidence and arguments for and against the particular problematic assertion. The point here is not to arrive at a consensus, but rather to help trainees reach a more critically informed understanding of the problem, to enhance their self-

awareness and their capacity for self-critique, to help trainees to recognise and investigate their assumptions, to foster an appreciation among trainees for the diversity of opinions and perspective that emerge within the context of open and honest discussion, to encourage attentive and respectful listening, and to help individuals to take informed decisions (Brookfield & Preskill 1999).

The instructor would put forward a problematic statement arising from either a real-life situation or a fictitious situation related to some aspect of diversity. The instructor would then facilitate an open discussion on the issue. The trainees would be encouraged to be objective in presenting their arguments and open to reviewing the evidence and arguments provided by their fellow trainees for and against the statement being discussed. Through the critical discussion, trainees will become aware of their assumptions and perspectives on the issue discussed and how these may differ from those of others.

The use of scenarios and role playing can also be valuable in facilitating the development of reflexivity in adult educators. In general, role playing accelerates the acquisition of know-ledge, skills and attitudes by focusing on active participation and sensitisation to new roles and behaviours. The opportunity to engage in situations that are similar to real life helps trainees to practice and retain information, and enables the transfer of knowledge and skills to everyday life (Dawson, n.d.). Providing trainees with realistic diversity scenarios will help them develop an understanding of the complexity of diversity issues by taking on the perspective of another. Role play can also be used to have trainees demonstrate how one would respond in a given situation and to assess the reasons for such responses.

In the classroom, trainees are presented with real-life scenarios depicting a classroom problem, and they are asked to act out the situation responding to the embedded challenge. Following the role play, the instructor would facilitate a discussion about what was enacted by the trainees and the decisions they made in addressing the challenge. This process of reflection presents another avenue for self-know-ledge, reflection-for-action.

This strategy is close in nature to the group discussion approach discussed earlier. This is because the case usually serves as a catalyst for an open group discussion. Case studies are useful in helping individuals to analyse their values on various social issues involving many people and varying viewpoints. Case studies are used to demonstrate different ways of thinking about the same issue.

As a strategy for encouraging reflexivity, the instructor would select cases adopted from actual situations, either independently or in collaboration with the trainees, reflecting diversity scenarios. Trainees would be required to read the case and independently articulate their own response. Then the instructor would facilitate a discussion around the case during which trainees would have the opportunity to share their perspectives on the matter. The discussion around the case allows trainees to expose and reflect on the lens through which they view various diversity-related issues. It also helps them to clarify their beliefs, assumptions, biases and contradictions.

Today’s world is characterised by internationalisation, globalisation and increased levels of migration. As a result, the issue of diversity has gained in importance within our societies and, importantly, in our learning spaces. Adult educators must develop skills and competencies to manage diversity in their classrooms and to create a learning environment in which all learners feel respected and are therefore willing to participate. The adult educator should develop an appreciation of the need to constantly examine his or her assumptions, personal beliefs and dispositions, and to have an increased awareness of how the resulting behaviours and attitudes play out in their classes. This puts the educator in a better position to create and maintain more inclusive classrooms.

References

Avery, D. R. & Thomas, K. M. (2004): Blending content and contact: The roles of diversity curriculum and campus heterogeneity in fostering diversity management competency. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 3(4), 380–396.

Barrett, S. (2012): Teaching beyond the technical paradigm: A holistic approach to tertiary professional education. In: Journal of Education and Development in the Caribbean, 14(2), 1–18.

Brookfield, S. D. (1995): Becoming a critically reflective teacher. San Francisco, CA: Jossey- Bass Publishers.

Brookfield, S. D. & Preskill, S. (2005): Discussion as a way of teaching: Tools and techniques for democratic classrooms (2nd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Brown, H. N. & Sorrell, J. M. (1993): Use of clinical journals to enhance critical thinking. In: Nurse Educator, 18(5), 16–19.

Cunliffe, A. (2004): On becoming a critically reflexive practitioner. In: Journal of Management Education, 28(4), 407–426.

Darkenwald, G. G. & Merriam, S. B. (1982): Adult Education: Foundations of Practice. New York, NY: Harper and Row.

Davies, E. (1995): Reflective practice: a focus for caring. In: Journal of Nursing Education, 34(4), 167–174.

Dawson, G. A. (n.d.): Integrating emotional intelligence training into teaching diversity. Business Quest.

Dewey, J. (1933): How we think. New York, NY: Heath and Co.

Freire, P. (1995): Pedagogy of hope. New York, NY: The Continuum Publishing.

Gardenswartz, L. & Rowe, A. (2003): Diverse teams at work: Capitalizing on the power of diversity. Society For Human Resource Management. bit.ly/2r4ZWFv

Hardy, C. & Palmer, I. (1999): Pedagogical practice and postmodernist ideas. In: Journal of Management Education, 23 (4), 377–395.

Jarvis, P. (2010): Adult Education and Lifelong Learning: Theory and Practice (4th ed.). Oxon, OX: Routledge.

Kolb, D. A. (1984): Experiential Learning. New Jersey, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Laughran, J. (2005): Developing reflective practice: Learning about teaching and learning through modeling. London, England: RoutledgeFalmer.

Mezirow, J. (1995): Transformation theory of adult learning. In: Welton, M. (ed.): In defense of the lifeworld: Critical perspectives on adult learning, 39–70. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Mezirow, J. (1997): Transformative Learning: Theory to Practice. In: New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, 74, 5–12.

Schon, D. A. (1983): The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. New York NY: Basic Books.

Villegas, A. M. & Lucas, T. (2002): Preparing culturally responsive teachers: Rethinking the curriculum. In: Journal of Teacher Education, 53(1), 20– 32.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978): Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Shermaine Barrett (PhD) is a Senior -Lecturer at the University of Technology, Jamaica. She currently serves as Vice President for the Caribbean Region of the International Council for Adult Education (ICAE) and President of the Jamaican Council for Adult Education (JACAE). Her research interests include adult teaching and learning, workforce education, and teacher professional development.

Contact

shermainebarrett@gmail.com

DVV International operates worldwide with more than 200 partners in over 30 countries.

To interactive world map