From left to right:

Uwe Gartenschlaeger

DVV International, Laos

Souphap Khounvixay

Non-Formal Education Development Centre, Laos

Beykham Saleumsouk

DVV International, Laos

Abstract – Using the Curriculum globALE to train adult educators in Laos, one of the remotest countries in Asia, turned out to be a project that was both challenging and rewarding at the same time. As an output-orientated framework, the Curriculum globALE is highly amenable to being adapted to suit local needs whilst providing an orientation with regard to the learning content of a training cycle. The implementation process clearly demonstrated the need not to focus exclusively on transferring knowledge and skills, but to simultaneously develop participants’ personal abilities when it comes to critical thinking, decision-making, communication and leadership.

“My new teaching techniques have boosted my confidence”, is how Ms. Naphayvong from the Vocational Education Development Institute describes the impact of the Training of Master Trainers that was implemented in Laos between 2015 and 2017 (DVV International newsletter 2017: 13). Her feedback specifically addresses two dimensions that are crucial for understanding the project: professional and personal growth. This article describes the journey taken by this capacity building project to empower adult educators in one of the most remote countries of Asia.

“The quality of non-formal education is poor, and the non-formal education services are scattered around at local level (…)” (Ministry of Education and Sports 2015). This observation from the key policy document of Laos, the Education Sector Development Plan, was clear to all as the process started. In fact, Laos does not have any structured pre- or in-service training for adult educators. In line with the UN 2030 Agenda, which sets out the need for high-quality training of teachers and trainers, DVV International and the Department for Non-Formal Education of the Laotian Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports decided to initiate an experimental training cycle for more than 30 trainers and facilitators. The programme design was based on several core decisions:

To use the Curriculum globALE as a reference point for the training cycle. The Curriculum globALE is an output-orientated curriculum, developed jointly by the German Institute for Adult Education (DIE) and DVV International to equip training providers with a basic standard model for capacity building. It is unequivocally amenable to local adaptation.

As the team of trainers was scattered all over Asia and Australia, the preparation of each module demanded on the one hand the use of digital communication tools and cloud solutions. On the other hand, a standard preparation schedule was agreed: The international trainers arrived in Vientiane at the latest two days before each training course in order to fine-tune the agenda for the upcoming module. These preparation sessions turned out to be both exciting and challenging, especially for the Lao team, as they had to translate and transfer much of the agreed content into the Lao language and context.

The team realised during the preparation process that some of the material was already available in Laos. Government and development partners have developed various handbooks, manuals and curricula in recent decades. It was possible to use and adapt many of these, so that there was no need to “re-invent the wheel”, and previous work could be built on.

Another decision was taken regarding the sequence of the training modules. The Curriculum globALE recommends the following:

Module 0: Introduction;

Module 1: Approach towards adult education;

Module 2: Adult learning and adult teaching;

Module 3: Communication and group dynamics in adult education;

Module 4: Methods of adult education;

Module 5: Planning, organisation and evaluation in adult education.

While discussing this scheme in the team of trainers, it was agreed that it would be appropriate in the Lao case to start with the more practice-orientated modules. The reason was simple: In Lao culture, learning relies more on experiences and exchange than on intellectual learning pure and simple. This shift anchored the learning on the experiences of the learners themselves.

After restructuring the modules, the training cycle for Lao trainers was ordered as shown in Figure 1.

The needs assessment was carried out during Module 0. Participants were asked to reflect on and introduce their working environments, experiences and expectations. The results were used to design the subsequent modules.

Implementation posed several challenges for the team of trainers. Most of the participants were accustomed to traditional teaching and learning approaches based on a teacher-centred concept. This includes a limited set of methods, mainly lecturing. When interviewed at the end of each training course, many participants expressed surprise at the process via which the training had been delivered. Most of the activities in this project incorporated principles of adult learning in the learning process itself, inspiring the participants to reflect and engage in further study. They were initially frustrated and full of questions: What is the main objective of this topic? We are experienced experts, why do we need to play this game? They faced challenges when it came to linking the learning experience with the objective of the training. At the same time, the attempt to replace the traditional lecturing and instruction-based teaching with interactive methods was appreciated and well received by the overwhelming majority of the participants during the process. This echoes experiences from similar cases in other countries where traditional teaching/learning settings are predominant. In order to keep the participants motivated and on track, it turned out to be crucial to synthesise the learning outcomes at the end of each unit.

This observation goes hand in hand with another experience: Participants who are accustomed to a traditional teaching environment, dominated by knowledge transfer pure and simple, become confused and – in some cases – draw the conclusion that the facilitators lack knowledge. It was helpful here to rely on a mixed team in which international experts (traditionally highly valued in Laos) could support the learning process by explaining the conceptual background behind the non-traditional facilitation approaches that were used.

The participants came from a wide variety of backgrounds. Their formal educational background varied from PhD to higher secondary diploma. They came from different parts of the country and held a wide range of positions in the official hierarchy. This had the potential to create misunderstandings and tension in a society where hierarchy is extremely important and the learning culture differs from one part of the country to another. The team of trainers devoted sufficient time to developing social and emotional skills aiming to bridge these gaps. This ensured that the acquired learning outcomes could be translated into different contexts as cross-

cutting issues of adult learning principles. It furthermore emerged that the participants found communication across barriers of hierarchy, institutions and regional affiliations to be inspiring.

Most of the participants were unable to communicate in English. The first two modules were mainly implemented by the international team, using translation via interpreters. This was time-consuming, and led to several misunderstandings. As time passed, it became apparent that constantly working in the international team gave the Lao facilitators increasing confidence and skills. This enabled them to implement the subsequent units as key trainers, with the international team supporting, mentoring and focusing on the design of the agenda.

All in all, the Training of Master Trainers turned out to be a learning journey not only for the participants, but for the facilitators as well. By engaging in an open process, involving the new paradigm of teaching/learning, and understanding local people’s learning methods, as well as their perceptions of learning activities, it was possible to balance theory and practice and deliver the content in a manner that ensured professional and personal growth.

There are three possible ways of describing the impact of the training of Master Trainers. The first way is to analyse the project using the OECD’s DAC criteria1, a standard tool used in development cooperation. In his research based on interviews with the participants and trainers, Professor Bruce Wilson from RMIT University in Melbourne described the relevance of the programme as follows: “The programme has contributed to the heart of non-formal education work through a core focus on adult learning principles.” The effectiveness of the training was based on the design of the training cycle: “As each workshop was activity based, participants were challenged to act in ways which were new for them, offering each participant the opportunity to recognise their capacity to support learning in others in ways which they had not tried previously. There were no dropouts, and almost all participants were able to conduct at least one outreach workshop.” The design was also instrumental for the high level of efficiency, as it allowed participants to learn without “disruption to ongoing non-formal education activities.” The partnership of higher education, international and non-profit organisation minimised the costs. “Participation of learners was a key ingredient in both the workshop learning processes themselves, and in the approaches which the Master Trainers were encouraged to use with their own learners.” By stressing this approach in several modules, participants were “not only (able) to increase the impact of their own non-formal education work, but also to recognise how they might contribute to the professional development of other educators” (all quotations are taken from Wilson’s report). As a result, it was possible to recognise outreach activities as a main impact of the training beyond the participants’ individual professional development. Lastly, the sustainability of the action relies on both the commitment of the Lao partners, and on the broader recognition that the Master Trainers’ expertise in adult learning can make a more general contribution to professional development within the education and labour sectors in Lao PDR.

Testimonials from participants:

“I wasn’t very aware of the non-formal education sector before attending this programme. I didn’t know exactly what it was because I was limited to my knowledge within my department, which conducts courses on vocational education lasting from six months to one year. A lot of our students want to continue learning even after the course, but are deprived of that opportunity as they do not have formal degrees or even an equivalency certificate. This training has not only been a learning experience, but also a good meeting ground for people from different organisations working in the same sector to come together and share their experiences.”

Chanthanom Theangthong,

Lao Youth Union

“What impressed me most was experiencing that education does not always mean sitting still, but that you can teach and learn through being active. We learned how to integrate ice-breakers, energisers and activators into teaching practice. These methods made learning much more fun than I had imagined it would be. I also learned how important the learning environment and mutual respect between learners and trainers are. Despite the fact that the participants had different starting points in terms of knowledge, as well as diverging positions, ages and sexes, we all had the same rights and were treated in the same way. I felt highly appreciated, and this made me more confident when it came to sharing ideas, interacting with other people, helping others, listening, learning new things, and so on.”

Amphone Lorkham,

Non-Formal Education Development Centre

“I am a teacher by profession, and imparting knowledge is what I do, so I feel that the training was highly relevant and enriching for me. I am very glad that I attended this training as I feel that I have learned a variety of techniques that I can use with my students. I like how participatory methods were used to introduce new concepts of adult education, and how we learned through involving activities. I look forward to using this approach in teaching with my students. I have attended a few training courses in the past, but I feel that I have been able to gain most from this Master Training of Trainers.”

Latdavanh Bounyaveth,

Vocational Education Development Institute

This leads us to the second possible way to explore the impact of the project: the numerous follow-up activities, including outreach training within the non-formal education system, and the recognition and demand that the Master Trainers experienced outside their sector. Based on their experiences in training, a module on adult and lifelong learning was introduced into the teacher education programme at the National University of Laos, and is currently in the process of being adopted at other universities and teacher training colleges. Laos’ biggest education project, the Australian- and EU-funded BEQUAL programme for reforming primary education, used the Master Trainers for various components, including the training of pre- and in-service teachers and pedagogical advisors. The Swiss Red Cross and the Don Bosco Training Centre were among other organisations that took advantage of the Master Trainers’ expertise.

Perhaps the most valuable impact of the project is in the personal development of the participants. One of the main lessons learned was in fact that, in a Laotian context, a successful training concept should always include personal development, not only in terms of teaching skills, but including a broad range of soft skills such as teamwork, decision-

making, critical thinking and presentation skills. Evaluating these developments is somewhat complicated. They were however appreciated by the team of trainers and – more importantly – by the participants themselves. The testimonials presented in the box on page 25 try to cover this aspect.

This article has constituted an attempt to describe the design and implementation of a training cycle for adult educators in one specific country in Asia. The Curriculum globALE played a key role in this endeavour. This experience has taught us that:

1 / More information on the OECD DAC criteria at bit.ly/2ZuCn5V and https://bit.ly/31Kn0bc

DVV International, DIE (2015): Curriculum globALE. 2nd edition.

https://www.dvv-international.de/en/materials/curriculum-globale/

DVV International Regional Office Southeast Asia (2017): Newsletter 2/2017.

Ministry of Education and Sports (2015): Education Sector Development Plan (2016-2020). https://bit.ly/2WQ10bt

Uwe Gartenschlaeger, M.A., studied History, Political Science and Philosophy at the Universities of Berlin and Cologne. After working for four years with a church-based adult education provider specialising in topics of reconciliation and history, he joined DVV International in 1995. He held the post of the Institute’s Country Director in Russia and Regional Director in Central Asia. He has been DVV International’s Regional Director in South and Southeast Asia since 2015.

Contact

gartenschlaeger@dvv-international.de

Souphap Khounvixay holds a Master’s degree in Education from the University of Adelaide, Australia, and is a co-facilitator for the training of Master Trainers using the Curriculum globALE as the first nation in Southeast Asia. He has specialised for the past decade in adult education, curriculum development, non-formal education, researching and evaluation in education in the Lao context.

Contact

souphap@gmail.com

Beykham Saleumsouk is a project manager at DVV International’s Regional Office Southeast Asia. Having worked in the development sector for almost ten years and specialised in youth development for more than seven, Ms. Saleumsouk ran a local non-profit organisation for many years, conducting and organising training courses for volunteer internship programmes. She is currently working with DVV International in Laos on capacity-building for non-formal education staff on adult education, project management and development of training plans and curricula.

Contact

saleumsouk@dvv-international.la

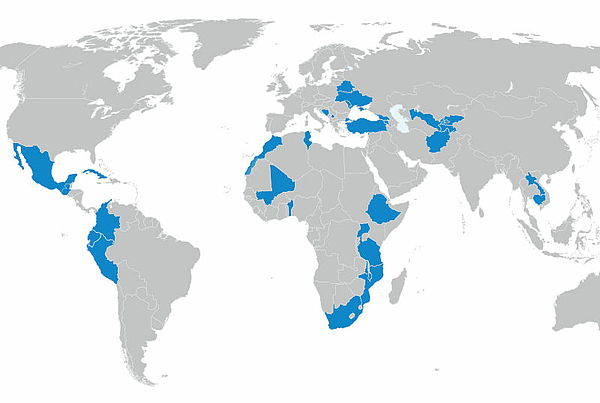

DVV International operates worldwide with more than 200 partners in over 30 countries.

To interactive world map